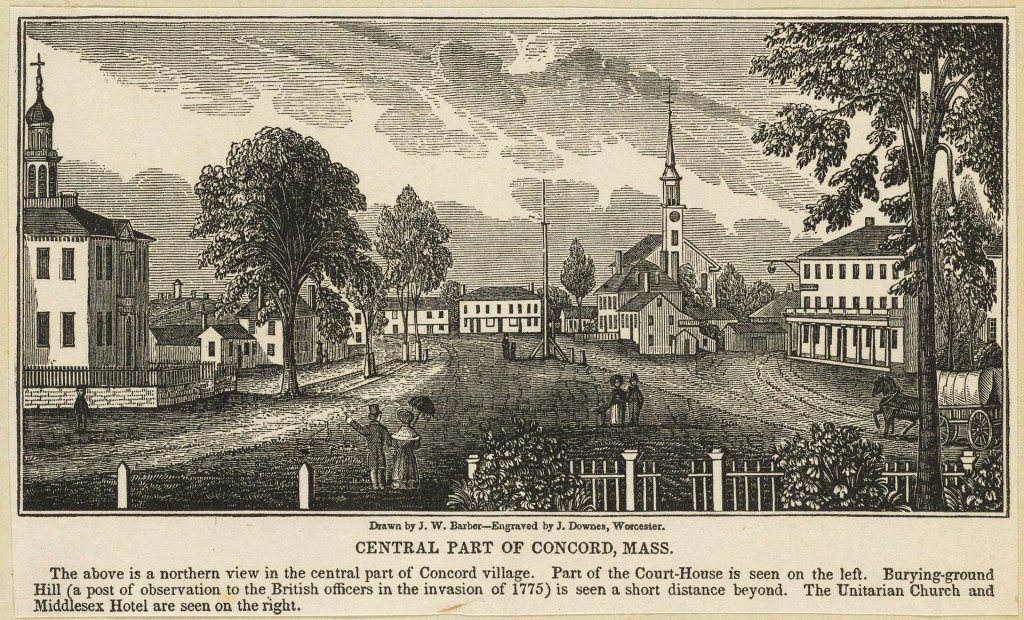

(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

People do not seem to realize that their opinion of the world is also a confession of character.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

I strongly agree with Emerson on this point, and have held the same opinion since long before I noticed what he had to say about it. Candidly, it’s sneering cynics — they exist everywhere, I suppose, but I personally encounter them most often in a particular strain of (typically secular apostate) anti-Mormonism (most recently in certain reactions to the General Authority stipend “scandal”) — who seem to illustrate the principle most clearly.

I can’t help but think of Lord Darlington’s definition of a cynic, in Oscar Wilde’s comedy Lady Windemere’s Fan, as “a man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.”

I love Switzerland. But I can’t count the number of times when some cynical Swiss or other, referring to religious faith and churches, would move his thumb back and forth against the opposing fingers of the same hand as if manipulating coins or bills and say, with a knowing smirk, Alles geht um das (“It’s all about that”) or Alles geht um das Geld (“It’s all about money”). The remark always seemed to me more likely an unwitting confession than an accurate description of others.

In an odd way, too, I’m reminded of the great Edmund Burke’s reaction, in his Reflections on the Revolution in France, to the news of the death of Queen Marie Antoinette on the guillotine. Although a member of Parliament, he had been sympathetic to the grievances of the American colonists and strongly opposed to British attempts to put down the Revolution by force. But the French Revolution, in his judgment, was a very different thing:

“I thought ten thousand swords must have leaped from their scabbards to avenge even a look that threatened her with insult. But the age of chivalry is gone. That of sophisters, economists, and calculators, has succeeded; and the glory of Europe is extinguished for ever. Never, never more shall we behold the generous loyalty to rank and sex, that proud submission, that dignified obedience, that subordination of the heart, which kept alive, even in servitude itself, the spirit of an exalted freedom.”

One of the members of my doctoral committee — I must say that I found him deeply impressive and that I wouldn’t actually consider him a cynic — was a prodigiously learned historian of the pre-modern Near East who, while not a Marxist, took a determinedly economic view of everything he studied. Which, since he specialized in Islam and its Middle Eastern religious antecedents, seemed to me a very serious defect. I actually credit Marxist and other modern historians (including those of the rather anti-Marxist Annales school) with bringing long overdue attention to economic and social factors that had previously been neglected. But the emphasis can and often does go too far. It can become a crude reductionism. My professor wasn’t by any stretch of the imagination “crude.” He was brilliant and insightful. But, in what always seemed to me a case of strange blindness, he was apparently unable to believe that any historical actor ever really did anything for non-economic reasons.

At one point, we clashed over a draft-chapter of my dissertation in which I described an event in seventh-century Iraq as an expression of a proto-Shi‘ite religious sensibility. No, he said, it was a fiscal protest against early Umayyad tax policies. I responded that it was an act motivated by devotion to the family of the Prophet, and that the hundreds of men involved in it — ordinary townsmen and farmers — went, as they surely knew they were going, to absolutely certain death at the hands of a professional army about fifteen times the size of their group. How could they possibly have hoped that doing so would better their financial situation?

He was resolute. There was always, he said, an economic angle. People always act in their own self-interest. I argued that I myself, though I hardly considered myself a spiritual exemplar, routinely spent time and money and effort out of religious motivation in ways that not only didn’t advance my economic interests but regularly and predictably cost me, in temporal terms. And that I knew literally hundreds of people, and associated with many of them every Sunday, who did precisely the same thing. Regularly. Routinely.

He insisted nonetheless that he wouldn’t approve that chapter of my dissertation until I acknowledged the event in question as a fiscal protest. I refused. We were at an impasse until my wife’s insistence that I get the darned thing done and move on finally impelled me to make a change. The main text of my dissertation now features precisely the description that he wanted, accompanied by a footnote explaining that the description given in the main text was incorrect and had been written under duress. That proved, amazingly enough, to be an acceptable compromise, and he signed.