Below is the eighth installment of an article that I wrote for Richard C. Martin, et al., eds., Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World, 2 vols. (New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004), on the subject of “Muslim Identity”:

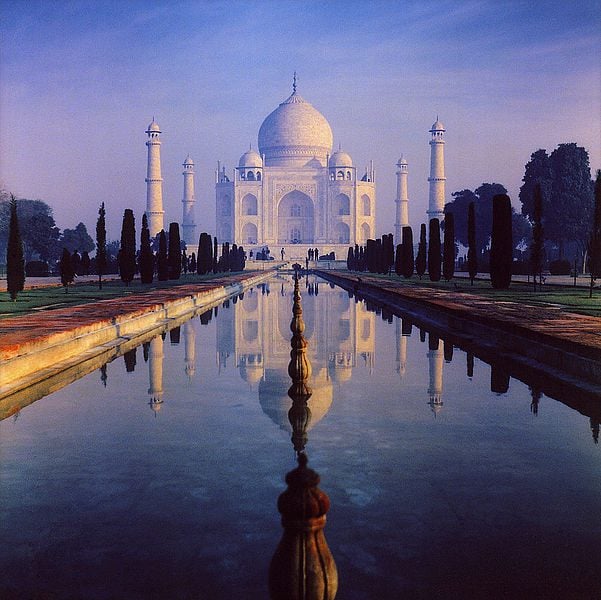

The Mughal Empire

Founded in 1526 and lasting until the mid-eighteenth century, the Mughal empire ultimately dominated the entire Indian subcontinent excepting the south. Yet the existence of a vast subjugated population of Hindus had always posed a problem for India’s Muslim rulers, and continued to do so under the Mughals.

Acutely aware of the problem, Akbar (r. 1556-1605), arguably the greatest of the Mughal emperors, chose a radical method of dealing with it. He integrated Hindus into all levels of imperial administration, married Rajput princesses, and abolished the jizya tax on non-Muslims. Worse, in the eyes of many devout Muslims, he began to experiment with an eclectic blend of Islamic and Hindu concepts. Akbar’s actions, in their view, represented a serious threat not only to the Islamic identity of Muslim India but to Islam itself.

The most significant opposition to Akbar’s syncretistic liberalism emerged out of the Naqshbandi Sufi brotherhood, which helped to foster a religious revival among Indian Muslims in the face not only of the emperor’s heresies and the resurgence of local Hinduism, but, as time passed, in opposition to Portuguese, Dutch, English, and French incursions into India. Ahmad Sirhindii (d. 1624), an Indian Sufi who powerfully influenced the development of the Naqshbandi order, is often considered by Muslim admirers to have saved Indian Islam.

Certainly Sirhindi represented a challenge to Mughal authority. Accordingly, a subsequent emperor, Awrangziib (r. 1658-1707), banned portions of his writing. But as Naqshbandi-inspired Islamic opposition grew, and amid spreading Hindu and Sikh restiveness that many Muslims attributed to Mughal laxity, Awrangziib also found himself obliged to dismiss non-Muslims from government service and to replace them with Muslims. Furthermore, under pressure from the orthodox ‘ulama’, he ordered the restoration of the jizya tax and reimposed Islamic shari‘a law.

But Naqshbandi revivalism was by no means limited to the Indian subcontinent. As early as 1603, Naqshbandi emissaries had entered the Arabic lands, and, soon thereafter, texts of the order were being translated from Persian into Arabic. The important Naqshbandi figure Shah Waliullah of Delhi (d. 1765), in fact, sometimes composed his works in Arabic, probably in a (successful) effort to address a much wider Islamic public.