For the last three of the four years that my wife and I lived in Ma‘adi, south of Cairo, we lived in a multi-level apartment building directly adjacent to Cairo American College. The apartments above us occupied entire floors, and were rented by people with relatively cushy corporate or diplomatic positions. By contrast, ours shared the ground floor with another relatively small apartment (a bit larger than ours) and with a rather large entryway. Thus, it was too small to be of much interest to the market consisting of better-positioned foreigners, and we were able to get it at a comparatively low cost. It was much nicer than the apartment in which we had spent our first year.

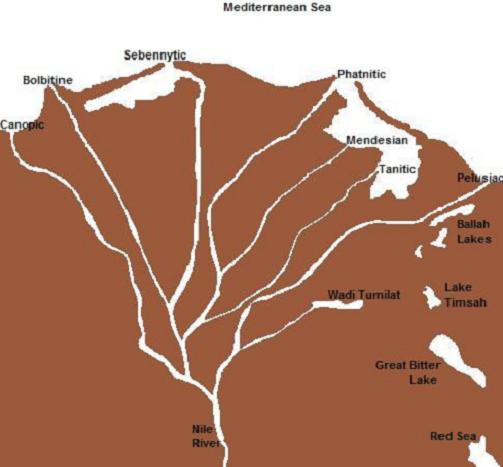

The building had a bawwab, or doorkeeper, named Kamal. He was an illiterate peasant from the area of the Nile Delta, north of Cairo. (Cairo sits at the point where the Nile River branches out into its delta.)

We came to like Kamal very much. Unfortunately, he’s probably long dead by now: Like many Egyptians, and especially like many very poor ones (at least back then), he smoked several packs of cigarettes a day, and he had already developed a chronic and very deep cough.

For the moment, three memories about him:

First, for much of the time that we lived in that apartment, Kamal lived outside our window, literally in a very large cardboard box. During our last year or so, however, the owner of the building had a small but permanent one-room shack built — not much larger, really, than the box — for him to sleep in. It was finished in the same tan stucco that covered the building itself. I was pleased for Kamal and, when I next visited with our landlord to pay our rent, I complimented him on having provided our bawwab with a nicer place in which to live. He looked at me as if I were from another planet. He had built it, he explained rather coldly, because the cardboard box was ugly and he wanted his building and its surrounding area to look nicer. Plainly, Kamal himself, the human being, didn’t matter at all to him. I had never overly much liked the landlord; I liked him considerably less after that conversation.

Second, after some time living in our new apartment, my wife and I bought a cheap black-and-white television set so that I could listen to the news and to Arabic programming and so that we could have some evening entertainment at home. (Egyptian television sometimes even picked up American television series, and I still shudder to think what Egyptian audiences were learning about life in the United States from Dallas, which was broadcast just about every night during our last several months in the country.) When we left, we gave that television set to Kamal, so that he would have something to do while sitting out there alone at night. (We were also obliged to give him a letter certifying that it had been a gift, lest the police assume — since someone like him could never afford to buy a television — that he had stolen it.)

Third, Kamal was only permitted by our landlord to return to his wife and children in his small village perhaps once a month, for a couple of days. Maybe less often than that, actually. (He was rarely absent.) Once, when he went home, we loaned him our super cheap and super simple Kodak Instamatic camera after teaching him how to point, look through the viewfinder, and click. We also gave him a few rolls of film and taught him how to change them. When he returned, with lots of images of his family and the people in his village, we develped the film and gave the photos to him. But I’ve kicked myself for decades now that we didn’t make copies of those pictures. They’re the kind of images that we, as foreigners, could never, ever, have obtained. Our presence would have disturbed their normal routine. They wouldn’t have been natural. But those photos were taken by one of their own, a peasant like themselves, speaking their dialect, dressed like them. How I wish that we had copies of those photographs!