(Wikimedia Commons public domain photo)

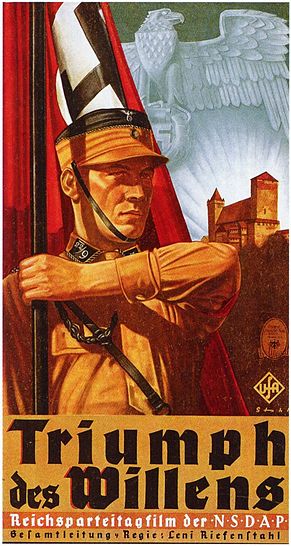

I’ve already shared a few items from Rolf Dobelli’s Die Kunst des klugen Handelns: 52 Irrwege, die Sie besser anderen überlassen (Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 2014) — “The Art of Smart Action: 52 Wrong Paths that Would Be Better Left to Others” — and may well share at least two or three more after today. All of Dobelli’s chapters are very brief, because they were all originally newspaper columns. Here’s something closely paraphrased from part of a chapter entitled “Warum Propaganda funktioniert: Schläfereffekt” (“Why propaganda works: The ‘Sleeper Effect'”), on pages 81-83:

During the Second World War, every country produced propaganda films. Their populations, and especially their soldiers, were supposed to fight enthusiastically for the Fatherland and, when necessary, die for it. The United States expended so much money for propaganda that the American War Department (which essentially became the Department of Defense in 1949) wanted to find out in the Forties whether the expensive films were really worth their cost. A number of studies were undertaken to determine how much the attitudes of regular soldiers had been changed at the end of watching a propaganda film.

The results were disappointing. The films didn’t strengthen enthusiasm for the war even slightly.

It wasn’t because the movies were badly made. It was, simply, that the audience knew in advance that these were propaganda films, so, no matter how logically they were argued and no matter how emotionally powerful they were, they were dismissed in advance.

However, nine weeks later something quite unexpected occurred. Psychologists measured the attitudes of the soldiers toward the war a second time. Soldiers who had seen the film nine weeks earlier now had a markedly higher commitment to fighting than did those who hadn’t seen the film. Plainly, the propaganda had worked, after all.

But this was puzzling, because it was well known that, typically, the persuasive power of arguments faded with the passage of time. It’s a bit like the decay of a radioactive substance. Having heard a powerful argument, one might immediately be all on fire about it. After a few weeks, though, one can’t quite remember why. And several weeks after that, essentially nothing is left.

With propaganda, though, the effect is pretty much the reverse. If one is influenced by propaganda, the effect actually gains strength with time. Why? The psychological term is sleeper effect — named, I guess, after a “sleeper cell” in espionage and related matters.

How does it work? With the passage of time, those who have been propagandized forget the source of the propaganda, where the information came from. So the natural dismissal of propaganda weakens. But the well-crafted propaganda point endures. So information or points conveyed by a questionable source actually gain trust or believability with time. The content of the propaganda message lingers, while the remembrance that it was propaganda melts away.

There is much to ponder in this, for both good and ill.

It’s one of the reasons, alas, that negative attack ads in political campaigns can actually be quite effective, however ham handed they may appear. It’s also among the reasons that advertising in general works, even though most of us would never consciously take guidance from commercials.