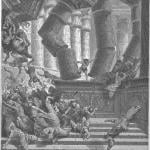

Wikimedia Commons public domain image

The frame story of King Shahryār and Shahrazād was known in Italy in the late Middle Ages. Traces of it linger, for example, in a novel by Giovanni Sercambi (1347-1424). Sometime thereafter, at the beginning of the sixteenth century, clear allusions to the story appear in the tale of Astolfo and Giocondo, which is featured in the 28th canto of Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso. It isn’t known how the story reached Italy, but it’s likely that travelers who had been to the Middle East may have brought it back in some form or another.

The whole Alf Layla wa Layla came to Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and the pivotal person in that appears to have been the French scholar Jean Antoine Galland (1646-1715), who published it for first time. Galland had been the secretary to a French ambassador in Near East, which is where he became acquainted with the Nights.

Galland was fortunate in the materials that came to his attention. These first began with stories of Sindbad the Sailor, which have been favorites among Western audiences ever since. Galland then realized that the Sindbad cycle was part of a larger collection (“1001 Nights”), although it must be noted that some manuscripts don’t contain Sindbad at all.

So he had four manuscript volumes of the Nights sent to him from Syria, and these remain—apart from a fragment discovered by the modern scholar Nabia Abbot—the oldest and best surviving text of the stories.

Galland began to publish his version of the Nights in 1704, and publication continued until 1717, two years after his death. He was a born story-teller, often re-arranging and paraphrasing his materials. Later, in fact, a Syrian Maronite Christian came to Paris and told him stories orally, which he transcribed and translated.

Galland’s version was the Nights for many generations of Western readers. And, in fact, two of his stories (for which the original Arabic was was unknown) were eventually rendered into Arabic—so that, in part but in a very real sense, Jean Antoine Galland provided the Nights for an Arabic audience, as well. For a time, indeed, some were willing to attach to the Nights any sufficiently riveting story that was found in Arabic.

I’ll mention two significant nineteenth-century English versions of the Thousand and One Nights. The first, by Edward William Lane, began to appear in parts in 1839 and was finished in 1841. It’s an incomplete production in many ways, but it features a valuable and full commentary.

The second was done by the colorful Victorian explorer Sir Richard Burton. It is, in some ways, the polar opposite of Lane’s rendition.

Posted from Jasper, Alberta, Canada