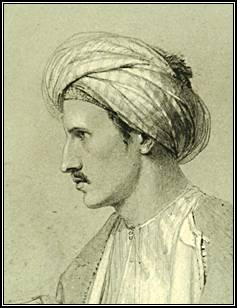

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

I’m very happy to say that I own complete sets — purchased during visits to Powell’s bookstore in Portland — of fairly early editions of both Sir Richard Francis Burton’s and Edward William Lane’s classic nineteenth-century translations of the Thousand and One Nights. They are, both of them, deeply flawed masterpieces by remarkable men.

Edward Lane (1801-1876) is also deservedly well known for other works, such as his 1836 book Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians and his great uncompleted Arabic-English Lexicon, which was published after his death (and of which I own and treasure not just one but two different editions).

The Lexicon remains, in many respects, the greatest Arabic-English dictionary of the classical language, although its coverage from the letter nun on is fairly sketchy. The Wörterbuch der Klassischen Arabischen Sprache set out, commencing with nun (!), to complete and ultimately to replace Lane’s Lexicon, and it will ultimately do so, I think, even if Lane’s marvelous work never altogether loses its value. But it’s deeply impressive to contrast the multi-scholar effort of the Wörterbuch with what Edward Lane was able to achieve largely by himself and without the support of modern technology. (He was often working from manuscripts, in fact.)

Lane’s Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians isn’t about what we would call “modern” Egyptians at all — and that, today, is what gives the book its remarkable value for us. The “modern Egypt” described by Lane was that of the early nineteenth century, before the advent of modern communications, largely before the advent of printing in the Middle East, prior to the massive impact of European civilization, before modernity transformed the region.

Lane lived in Cairo and traveled throughout the Sudan, often dressing as a Turk — the region was then under Ottoman Turkish rule — and spending day after day in mosques, coffee houses, and bazaars, conversing with the people, learning from them, taking reams of notes. His Egypt, with its harems and dervishes and beggars and magicians and street vendors, was much closer to that of the medieval Mamluks in most regards, and thus to the world of the Nights, than to contemporary Cairo. So his detailed account of the now-vanished world that he was still able to see directly and with his own eyes is of irreplaceable importance.

Lane published his illustrated translation of the Nights between 1838 and 1840, with copious explanatory annotations based on the same first-hand observations from which his Manners and Customs had drawn. In 1883, several years after Lane’s death, his great-nephew, the orientalist Stanley Lane-Poole, published those notes as a stand-alone volume, under the title Arabian Society in the Middle Ages.

Lane’s translation of the Nights was informed by his extensive experience in Egypt, but he didn’t always faithfully transmit the original Arabic. As I’ve said, many of the tales are not suited for children — and they would not have been well-received by the Victorian public. So, a devout Christian, Lane cleaned them up. Or, if he felt it necessary, omitted them altogether.

Posted from McCall, Idaho