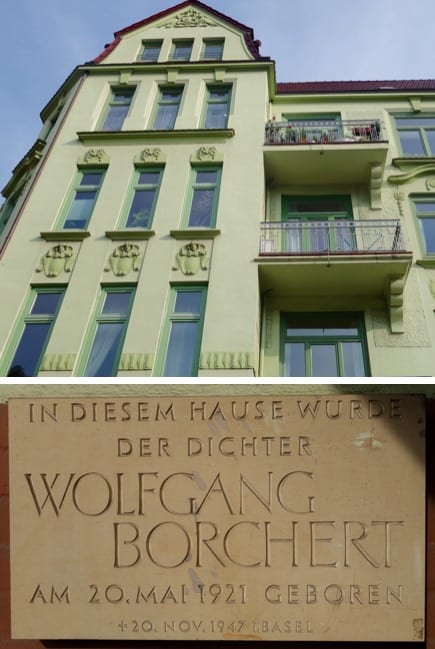

“The poet Wolfgang Borchert was born in this building on 20 May 1921.

+ 20 November 1947, Basel”

My wife and I are just back from the Brigham Young University campus, where we enjoyed a concert by the Utah Symphony entitled “Rhapsody in Blue.” As you might guess from that title, it was an (almost) all-Gershwin program.

It started out with Gershwin’s familiar Cuban Overture, featuring (as three of the other numbers on the program did) the pianist Kevin Cole, and that was followed by Sacred Geometry, by the Los Angeles-based composer Andrew Norman (b. 1979), which I really liked. Next came Gershwin’s Second Rhapsody for Piano and Orchestra. After the intermission, we heard Gershwin’s Variations for Piano and Orchestra on “I Got Rhythm” and his Promenade “Walking the Dog.” Finally came the great and sometimes even sublime Rhapsody in Blue.

Unfortunately, the life of George Gershwin (1898-1937), like the lives of so many other great geniuses, ended far too soon. He died in Los Angeles at the age of 38, probably from a brain tumor and related causes.

The brevity of such lives, a topic on which I often reflect, has been on my mind again lately because, the other day, I read a short story (“Das Brot”) by the German poet and playwright Wolfgang Borchert (1921-1947), whose most famous work is the still often-read and often-performed play Draußen vor der Tür (often titled, in English, The Man Outside).

Wolfgang Borchert was and is considered one of the great literary talents of modern Germany and perhaps the principal spokesman for the immediately postwar German generation, who have sometimes been called “die Jugend ohne Jugend” (“the youth without a youth”).

But his life was so terribly, terribly short: Although he opposed Hitler and Nazism — and paid for his opposition with multiple bouts of imprisonment (even, at one point, facing a prosecutor who sought the death penalty against him) — he was obliged to serve in the German military during World War Two, including a stint on the Russian front. He died of health problems incurred during his military service and his incarcerations just two years after the war ended, at the age of 26.

“Wir wollen nach Hause,” he wrote when he was 24, just at the conclusion of the war. “Wir wissen nicht, wo das is: zu Hause. Aber wir wollen hin.” (“We want to go home. We don’t know where that is: ‘at home.’ But we want to go there.”)

Such early deaths as those of Gershwin and Borchert are among the features of human life that make me impatient with triumphalist atheism: I can understand the belief that, well, they just died. They ceased to exist, and their genius vanished, its potential forever unrealized. And, sadly, that’s just the way it is. What I can’t understand is how anybody could possibly imagine that to be good news.