I confess that I’ve never understood the exultation and evangelical zeal that some claim to feel as atheists.

Let me be clear: I can easily understand coming to the conclusion that there is no God. The world is full of seemingly pointless suffering, painfully unanswered questions, dubious religious claims, historically shaky scriptural stories, hypocritical pseudoprophets, theologically-motivated wars and oppression, and the like. Moreover, naturalistic theories such as evolution seem (at first glance, anyway) to have undercut arguments from design for the existence of an intelligent creator.

However, I just can’t see how there being no God would be good news, worthy of celebration and of proselytizing on its behalf. (You may have heard the old joke about what you get when you cross an atheist with . . . umm, let’s say, a Jehovah’s Witness: Somebody who goes door to door for no apparent reason.)

Sure. The demise of God would seem to allow certain freedoms. Latter-day Saints, specifically, would get an extra day each week, ten percent of their gross income back, tea, coffee, wine, beer, brandy, cigarettes, and release from an increasingly unfashionable and always demanding sexual ethic. No more impossible demands like loving your neighbor as you love yourself, turning the other cheek, losing your life in order to save it, and being perfect like your Father in Heaven. Catholic priests could abandon their vows of chastity. Monks could forsake their vows of poverty and their chanting and, instead, participate in rave parties, follow the Kardashians, and subscribe to Cigar Aficionado. Once-Orthodox Jews could enjoy bacon bits in their salads.

But God’s absence also seems to deprive the acts undertaken with such freedom of any lasting significance. They become as trivial morally as many of them already were in other respects. Faithful spouses and utterly unfaithful playboys will rot alike, along with their partners, unremembered and irrelevant. And, if atheism is true, whatever good things it confers (no time-consuming church responsibilities! no boring Sunday meetings! no guilt after getting drunk or spending quality time with pornographic videos! cocktail parties!) come at the high price of living in a universe that is entirely indifferent, one that could, in fact, easily be described as hostile except that it is completely unconscious and lacks any purposes or intentions at all. Lost loved ones will remain lost forever. Children will die, and will then be as if they had never lived. Everything human — the pyramids, happy families, Beethoven’s symphonies, children’s songs, the plays of Shakespeare, memories of holidays at the beach, the sculptures and paintings of Michelangelo — will perish, and there will be nobody, anywhere, to remember them.

I recall an odd conversation from some years back with an ex-LDS atheist who particularly despised the Latter-day Saint belief in the eternal nature of families — which, in her construal of the doctrine, decreed everlasting divorce of non-LDS spouses and never-ending separation of non-Mormon parents and children. Somehow, she preferred her own vision of the future, which denies conscious existence of any kind to everybody after death, without regard to creed, and, thus, declares that the grave portends permanent separation for all. Ashes can be commingled, I suppose, and bodies might be permitted to decompose side by side, but that seems to offer little comfort.

Bertrand Russell, who actually believed this, faced it squarely and put it eloquently:

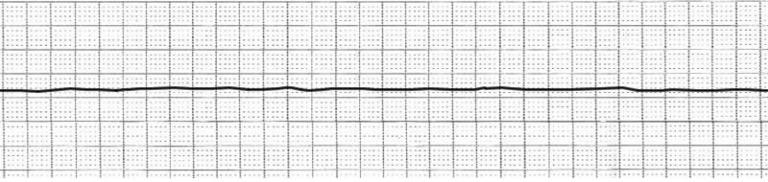

“That man is the product of causes that had no prevision of the end they were achieving; that his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and his beliefs, are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms; that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling, can preserve individual life beyond the grave; that all the labors of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and that the whole temple of Man’s achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins–all these things, if not quite beyond dispute, are yet so nearly certain that no philosophy which rejects them can hope to stand.

“Only within the scaffolding of these truths, only on the firm foundation of unyielding despair, can the soul’s habitation henceforth be safely built.”

Again, I can easily imagine coming to the sad and solemn conclusion that Russell’s vision of the universe is true. But I see essentially nothing in it to make one happy that it’s true.

Fortunately, it isn’t true.

There’s no cosmic requirement that the truth must be bad.