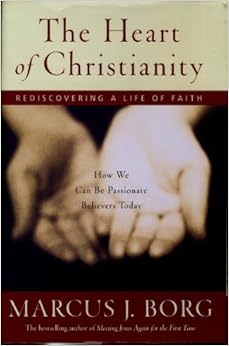

What are we to make of the Bible? It is a historical product that lacks historicity. God, according to the text, is real and he has in the past interacted directly with humanity. But what does that mean if the past depicted in the Bible is not always historically correct? This topic is addressed by Christian theologian and New Testament scholar Marcus Borg in his classic work The Heart of Christianity: Rediscovering a Life of Faith. I find his approach quite insightful. Borg’s study provides the following five points concerning the Bible as a historical product. From Borg’s perspective, recognizing these points can help readers address some of the concerns sometimes expressed concerning the Bible’s theological portrayals of God:

* The Bible is the product of two historical communities, ancient Israel and the early Christian movement.

* As such, it is a human product, not a divine product. This claim in no way denies the reality of God. Rather, it sees the Bible as the response of these two ancient communities to God.

* As their response to God, the Bible tells us how they saw things. Above all, it tells us how they saw their life with God. It contains their stories about God’s involvement in their lives, their laws and ethical teachings, their prayers and praises, their wisdom about how to live, and their hopes and dreams. It is not God’s witness to God (not a divine product), but their witness to God.

* As a human product, the Bible is not ‘absolute truth’ or ‘God’s revealed truth,’ but relative and culturally conditioned. To many, ‘relative’ and ‘culturally conditioned’ means something inferior, even negative. But ‘relative’ means ‘related’: the Bible is related to their time and place. So also ‘culturally conditioned’ means that the bible uses the language and concepts of the cultures in which it took shape…

* When the Bible is approached in this way, many of the problems that people have with the Bible largely disappear. The conflict between the Genesis creation stories and science vanishes. The laws of the Bible need not be understood as God’s laws for all time, but as the laws and ethical teachings of these communities. The stories of God destroying Israel’s enemies are Israel’s way of telling its story, just as violent destruction of the enemies of Christ is what some early Christians hoped for. Of course, this realization doesn’t make these ‘good stories’; but at least the problem of thinking of them as expressing the will of God disappears. In general, the literal and absolute reading of the Bible as infallible words of God disappears and is replaced by a historical and metaphorical reading (pp. 45-46).