[Open with dialogue with congregation about wounds]

Some wounds never really heal.

When I was a journalist, it was my job to bear witness to these kinds of open wounds that life inflicts on the unsuspecting. Like the mother who welcomed her son home in a flag-draped coffin. Or the parents of the teenagers who were pulled out of a car submerged in a frigid river. Or the couple who watched a fire consume a beloved home and the generations of memories that it had safe-guarded.

These are wounds I can’t imagine will ever really heal.

Truth be told, if we were to think back on our lives and experiences, we all have thesekinds of open wounds mark us.

How comforting I find it then in today’s gospel text to know that Jesus is no different.

To me, it’s the most striking element of the resurrection stories.

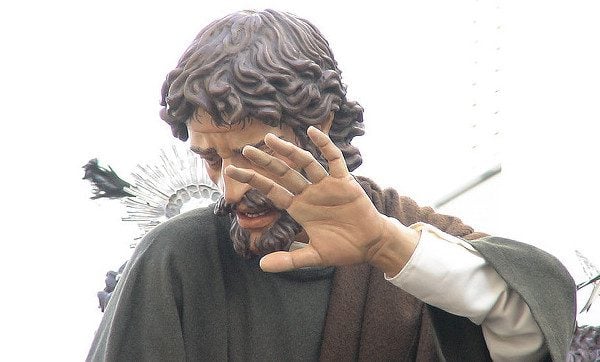

Jesus is still wounded in them all.

In fact, in many of the gospel stories, it is not until the disciples actually seethe wounds of Christ that they actually recognize Jesus for who he is. Until they see the wounds, Christ remains shrouded in mystery. Take Thomas in today’s gospel, for example. He doesn’t want to see the face of Christ as proof of the resurrection. Rather, he wants to see his wounds. Not because of some dark fascination or macabre obsession with the grotesque, but because, in some profound way,Thomas knew that it was Jesus’ wounds that now made him who he was.

Christ,in the resurrection, is known by his woundedness.

Ours is a faith that embraces wounds. It’s not that it celebrates pain or relishes in it. Nor does our faith ask us to seek out pain or suffering, as if our redemption is tied up with how miserable we can be for Christ.

But our faith refuses to gloss over our woundedness with hollow positive thinking.It refuses to ignore that basic tenet of human life. We will hurt.

Instead,it recognizes that our wounds, in so many ways, make us who we are. That suffering, failures, broken dreams, fractured relationships all shape our identities and even how we think about God, probably more than we’d like to admit.

Or, as Franciscan friar Richard Rohr reminds us, these wounds, and what we dowith them, is at the heart of faith.

And perhaps more importantly, faith is about what we do with our pain and our wounds within community, says M. Scott Peck. We don’t like to share our wounds. It’s frightening to think of being that vulnerable with others. Sometimes that’s appropriate, because we aren’t emotionally ready to share those wounds, but eventually true community asks us to expose our wounds and weaknesses to each other. It asks us to let ourselves to be affected and changed by the wounds of those around us. Because it is in this fertile ground,that compassion for each other and the love of Christ begin to grow and flourish. But Christian culture is often more interested in championing success stories as evidence of faith and divine favor. What would it be like, if instead, we followed Christ and embraced the holiness of our wounds, our failures, and our shortcomings, the cracks in our oppressive facades of perfection we create for ourselves, those cracks in which the light of God can shine through?

In his book The Illumination, novelist Kevin Brockmeier imagines a world in which one day, for unknown reasons,people’s pain begins to emit light. Be it a headache, sore feet, depression, or cancer, light one day begins to pulse from each person’s wounds— sometimes in sharp shafts of light, other times in a luminescent sheen over a person’s skin.

The entire novel explores how the world changes when people can no longer hide their pain. It considers how relationships and even fleeting interactions in society are transformed when we no longer lead with our best foot forward but with our deepest pain glowing.

How would we change if we as a church saw each other’s wounds and darkness as clearly as we could see the stars in the night sky?

It’s a beautiful, if unnerving concept really, to not be able to hide our pain — our wounds — from each other. Sometimes we need the space to deal with our own wounds and know it is safe to speak about them with others.

But what would it be like to see the doctor’s pain as she heals a patient of his own? What would it be like to see the soldier’s fear as he acts with bravery? What would it be like to see the priest’s doubt as she preaches faith?

Would we then see the hope in wounds? That it is the pain in the doctor enables empathy and healing, the fear in the soldier facilitates courage, the doubt in the priest incubates faith?

How would we change if we could see the wounds our words and actions do, when we,because of our own pain and woundedness, fling fear and pain out at others like deadly weapons?

Our woundedness lies at the heart of so much of our lives, affecting our interactions with each other and affecting how we see the person in the mirror.

Woundedness lies at the heart of the church, too. In fact, wounds are the foundation of the church. In our gospel text today, Jesus breathes the Holy Spirit into the disciples. This sending of the Holy Spirit into the world is an event ofPentecost, a day we traditionally consider to be the birth of the church. We usually think of it in terms of tongues of fire and wind, but here in John’s text, the Holy Spirit is the breath of Christ, and that breath is intimately tied up with the wounds of Christ.

Too often, though, in our culture, church is the last place where we feel we can bring our woundedness, our vulnerability, our failures, our doubts, and our pain. Perhaps we fear admitting these things will make us seem like bad Christians. Maybe it’s simply that our culture prides itself on individualism and self-sufficiency that in the face of failure, pain and hardship, we follow the advice we give to our children whenever the scrape a knee. “Get over it,” we say to ourselves. “It doesn’t hurt that bad.”

Maybe we’ve internalized that childhood message that pain and wounds really aren’t that important, that they are best ignored, best hidden under a bandage that will make it all go away.

But it doesn’t go away. Christ in our story today reminds us of this today.

He is still wounded. Those unhealed wounds are the shadow side to this celebratory season in which we are to revel in the triumph of our Lord over death and its sting.

But we must not forget that our Lord still has wounds.

Wounds, not scars. These are not faded blemishes where the skin has closed and only distant memories of the injury remains. Rather they are open wounds: holes in each hand, each foot where the nails of execution pierced him. A ragged,open gash where the spear tore into his side and his vital organs.

The crucifixion wounds do not heal. They remain open, eternally. The resurrected body of Christ remains marked by his earthly suffering, forever.

But, his wounds no longer bleed, either. He doesn’t leave bloody footprints in thePalestinian sand. He isn’t hobbled or debilitated by his wounds.

This is the promise of the resurrection — not that we will not longer be wounded. No we will always be wounded. Between hunger and poverty, war and terror, sickness and death, abuse and hate, none of us will escape unscathed without wound that do not heal.

But as people of the resurrection, our promise is that our wounds will not and forever bleed us of our lives and our vitality. The promise of the resurrection is not the assurance of an easy, simple life without wounds, but a life in which our wounds, even if they define us, do not bleed us. The promise of the resurrection is that, eventually, after the bleeding stops, our wounds, while they won’t ever heal, might just begin to heal others.

On my trip to the Holy Land in January, we met a Jewish-Israeli man named Rami El Hanan. Rami knows about wounds that will never heal.

In 1997, his 14-year-old daughter was killed by aPalestinian suicide bomber in Jerusalem. and suddenly, he was faced with the question of what to do with all his pain with his wounds.

In the midst of his overwhelming grief, one day he met a man who introduced him to two organizations (Combatants for Peace and Parents Circle) that brought together Palestinians and Israelis who had lost children and loved ones in the conflict.

Grieving and angry at all Palestinians because of his daughter’s death, he went, but remained skeptical from the beginning. But one by one, Palestinians got off a bus and greeted him with tears, with hugs,and with peace. Then, in a moment he would never forget, he saw an old Arab woman walk out of the bus. Against her all-black outfit, she had a locket with a picture of her six-year-old granddaughter, just like his own wife carried around a picture of their murdered daughter. And something changed in him as he witnessed this woman’s wounds, something he can’t fully explain to this day.

“I was 47 years old,” Rami told our group. “But today, I am ashamed to admit it, it was the first time in my life I had metPalestinians and saw them as human beings … not as terrorists.”

Rami saw the wounds of his sworn enemy, and it changed his life. He now travels throughout Israel and Palestine advocating for peace among high school students.

Rami told our group this, sitting in a small room, next to his best friend, Bassam Aramin. Bassam was a former Palestinian terrorist. But Bassam was also a grieving father, just like Rami. Bassam had lost his own daughter in the conflict, murdered in cold blood by an Israeli soldier.

The two men met one another in their pain, in their very deep wounds that will never, ever heal. But through the sharing of their pain, their wounds no longer bleed the life from them. Rather, they bring life and hope to each other and into one of the most wounded places in the world — the Holy Land.

Rami said something to us that night that will forever stay with me.

“We have an enormous ally on our side, which is the power of pain. You should know that the power of pain is tremendous. You can use it like you can use nuclear energy. To bring darkness and pain and you can use it to bring light and warmth.”

Rami is still wounded. Bassam is still wounded.Jesus is still wounded. And so are we.

But we are also people of the resurrection and a church formed in the experience of Christ’s wounds.

May we, like Rami, like Bassam, and like Jesus himself, have the courage, the vulnerability and faith to allow our wounds to transform the world with light and warmth and healing.

And in doing so, may we ourselves bring resurrection into a dying world still bleeding and hurting from so many open, gaping wounds.

___

This post is updated and remixed from a 2012 post, The Resurrection and Wounds that Don’t Heal.