Proper 19 — Year B — Mark 8:27-38

Ever since his baptism, Jesus’ world had simultaneously expanded and crumbled.

It had all started so promising, with the Spirit descending like a dove, the voice from the heavens declaring him the Beloved Son. It was a public declaration of his identity he didn’t take lightly, despite the problems it would cause.

See it didn’t take long for his parents and siblings to become deeply concerned with his behavior. They thought he was crazy, and said so in public no less.

Now there’s nothing like a public shaming in such a small town where news travels fast. It’s no wonder when he returns to his hometown he does so under suspicion and maybe even a little gossip. Folks haven’t forgotten that unfortunate incident when his folks said he’d cracked, and Jesus had disowned them publicly in return — declaring them no longer his true family.

Yes, they remember. How could they forget? So, of course, in his tiny hometown, Jesus isn’t a prophet, and certainly not the Messiah, they say. God’s son? Not likely, they laugh. He’s a carpenter’s son.

But Jesus had already severed that familial identity, a rather startling thing to do in his small town where family determined your future and your identity. John, the one who baptized him and witnessed the first declaration of Jesus’ identity, had offered him some comforting familial connection. But John, a dear friend who understood him better than anyone, was off in the woods eating bugs and honey not anywhere close enough to real connection.

So without a family to speak of any more, his friends now had become his kin, his familial identity.

But as painful as the fracture from family and home must have been for someone in first-century Palestine, Jesus had continued to do impressive public work so long as he avoided home.

On par, things seemed to be trending upward.

Then, he got the news that John had been murdered by the government, beheaded as a party favor.

It hit him hard when he heard, and he had gone off by himself to grieve. Suddenly, his calling and mission had a darker, more dangerous edge to it, a real-world reminder of where things might well be headed. Let this cup pass, Jesus might well have prayed. It’s not secret Jesus struggled with the specter of his suffering; it’s why temptation came to him in the form of avoiding it — whether Satan in the wilderness or Satan in Peter.

Then there had been the encounter with the Gentile woman, whose response had completely rearranged his understanding of the breadth of his own ministry and purpose. It called into question things he had been taught his entire life by rabbis, his family, and his culture in general.

So in a relatively short span of time, Jesus had been called crazy by his family, publicly disowned them in response, been run out of his childhood home without honor, lost his foundational mentor to a state-sponsored execution, and had his missional identity turned upside-down by a non-Jewish woman.

It is against this backdrop that Jesus asks the question of his friends, his new family.

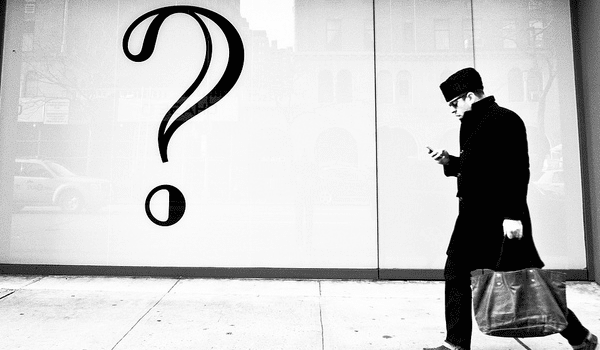

“Who am I?”

Set in this context and at a critical turning point in the gospel of Mark, this is a fundamental question of identity, if not outright crisis — not just for the disciples but for Jesus himself.

But that can be hard to hear with modern ears and generations of theology that assume Jesus possessed a kind of supernatural self-understanding that transcended human experience.

As 21st-century Westerners, we tend to understand identity — our self-understanding — as an individual exploration or experience. We take personality tests, facebook quizzes, and maybe spend a little too much time looking in the mirror asking ourselves who we really are. To us, leaving family and striking off on one’s own typically are seen as rites of passages, evidence of stability and a clear sense of identity.

But Jesus wasn’t living in an individualist culture like ours, but a collectivist one. He wouldn’t have formed his identity independent of those closest to him. In fact, given his time and place, to assume Jesus had a self-understanding completely independent of others would be to read a Western, individualist notion back into the text, argues scholar Richard Rohrbaugh.

It is easy to assume that Jesus knows with certainty the answer to his question, “Who am I?” (“Who do people say I am?” and “Who do you say I am?”), and that he’s using the exchange as a teaching moment for his disciples. It may be disorienting to think otherwise.

But we have to remember to deal with Jesus’ humanity in the gospels, not just his divinity.

Jesus was divine, but he wasn’t magic. He was human. And like all humans, he was finite and limited.

Like us, Jesus didn’t have some a priori understanding of who he was. He had to discover who he was. His mission wasn’t downloaded into his brain like Neo in The Matrix. He had to explore it. I don’t think, as he was lying the manger, he knew he was the Christ. I don’t think as he was growing up, apprenticing as a carpenter, he knew it either.

Like all humans, he had to figure things out, including the sometimes confusing question of identity and self-understanding. In other words, as fully human, Jesus didn’t get to cheat the emotionally, existentially and intellectually painful parts of every day living — of coming to understand who you are, what you are to do, and how and with whom you must do it.

And Jesus was a product of his time. Identity and self-understanding in his time and culture was constructed relationally. Identity tended to be communal, centered around family and generations of relationships. Who you were depended on who your family was. And at this point in his life, Jesus has lost his family and hometown connections. He was estranged from his mother and brothers, his closest thing to mentor has been murdered, and he had lost an argument with a Gentile woman.

In his time and place, this has all the makings of an crisis of identity. But instead of turning inward as we would, he turns to his friends — his new family — to ask his questions of identity. In other words, when we are trying to figure out our identity, we ask ourselves, “Who am I?” To get at the same question in first-century Palestine, we would ask others, “Who do folks say I am?” and “Who do you say I am?”

Peter proclaims Jesus’ identity as the Christ. If viewed through the lens of first-century identity and Jesus’ narrative context — family fracture, execution, religious disorientation — then the entire episode carries so much more dynamism than a mere rhetorical teaching tool as commonly assumed.

Given the cultural context, Peter’s statement about Jesus, at a minimum, crucially confirms Jesus’ identity and calling. Now we might begin to understand the urgency of Peter’s rebuke. When Jesus explains what it means to be fulfill the role of the Son of Man, Peter immediately seems to regret his statement. By his proclamation, Peter has unwittingly helped to set Jesus on a path to his own death.

If Jesus was in the midst of an identity crisis here, it isn’t impossible to think that he had realized exactly what role the Son of Man was to play and that he wasn’t quite sure if that was the role he was intended to carry out — or even the role he wanted. In a sense, he could be asking his friends whether this cup of suffering is for him. It would not be the first or the last time Jesus would be tempted to avoid suffering. Unwittingly, they say yes. The divine confirmation that comes shortly after — the transfiguration — has often been understood as meant for the disciples that Jesus is the Christ. Perhaps it was meant, too, for Jesus, a reminder of that first divine calling at the moment of his baptism, a reminder, as all callings are, not to forget who he really was.

It was a confirmation of his identity as the beloved Son, given in baptism and now confirmed within community. When Jesus discerns his identity in community, it does not sew up his understanding of himself tidily. We encounter him again in crisis in Gethsemane questioning his identity and begging for a different one. And while his disciples might have fallen asleep while he struggled, they didn’t leave him alone. They still went with him.

And that’s really the point. We can’t be who we are without a community who knows us, loves us, and believes in us even when they disagree with us. We can’t really follow God’s mission of love and justice in the world without friends who are more like family that remind us of who we really are. Because in the midst of loneliness and isolation, family fracture and marginalization, violence and ridicule, it can be all to easy to forget who we are and to what God calls us.

It can be all to easy to give into the temptation to just give up. And that’s when your community reminds you, in quiet and unexpected affirmations, in proclamations for you and for others, in the renewal of our baptismal covenant of who we really are.

See, all that modern identity being a internal process is a fiction. We need each other to know who we are. I am because we are.

Jesus was no different.

Sources: Rohrbaugh, Richard L. “Ethnocentrism and Historical Questions about Jesus” in The Social Setting of Jesus and the Gospels,edited by Wolfgang Stegemann, et al. Fortess Press: Minneapolis, 2002

Image Credit: Tom Waterhouse/Flickr (Used Under Creative Commons)