There’s a lot that’s not known about this early saint, but what is known isn’t exactly romantic.

From NPR, which peers into Roman history:

From Feb. 13 to 15, the Romans celebrated the feast of Lupercalia. The men sacrificed a goat and a dog, then whipped women with the hides of the animals they had just slain.

The Roman romantics “were drunk. They were naked,” says Noel Lenski, a historian at the University of Colorado at Boulder. Young women would actually line up for the men to hit them, Lenski says. They believed this would make them fertile.

The brutal fete included a matchmaking lottery, in which young men drew the names of women from a jar. The couple would then be, um, coupled up for the duration of the festival – or longer, if the match was right.

The ancient Romans may also be responsible for the name of our modern day of love. Emperor Claudius II executed two men — both named Valentine — on Feb. 14 of different years in the 3rd century A.D. Their martyrdom was honored by the Catholic Church with the celebration of St. Valentine’s Day.

Later, Pope Gelasius I muddled things in the 5th century by combining St. Valentine’s Day with Lupercalia to expel the pagan rituals. But the festival was more of a theatrical interpretation of what it had once been. Lenski adds, “It was a little more of a drunken revel, but the Christians put clothes back on it. That didn’t stop it from being a day of fertility and love.”

Around the same time, the Normans celebrated Galatin’s Day. Galatin meant “lover of women.” That was likely confused with St. Valentine’s Day at some point, in part because they sound alike.

Meantime, a website devoted to Irish history offers more — because Ireland, it seems, reportedly has the saint’s remains:

The first Valentine was a Roman priest martyred under the Emperor Claudius II in 269 or 270 AD, the second was a Bishop of Terni killed in the same century, and little is known of the third who died in Africa.

St Valentine’s Feast Day falls on 14 February, on which day lovers have customarily exchanged cards and other tokens of affection. It is not clear why Valentine should have been chosen as the patron saint of lovers, but it has been suggested that there may be a connection with the pagan Roman Festival of Lupercalia. During this Festival, which took place in the middle of February, young men and girls chose one another as partners. Legend, no doubt embellished if not entirely fictional, has it that the Roman Valentine resisted an edict of the Emperor forbidding the marriage of young men bound for military service, for which offence he was put to death.

Valentine’s Feast is also linked with the belief that birds are supposed to pair on 14 February, which legend provided the inspiration for Chaucer’s ‘Parliament of Fowls’. The crocus, which starts to bloom in February, is called St Valentine’s Flower. The earliest Valentine letter is found in the fifteenth-century collection of Paston Letters. The general custom of sending tokens on Valentine’s Day developed during the nineteenth century, and in the present century has spread to the east, where it appears to be particularly popular in Japan. The exchange of Valentine cards, flowers, sweets and other gifts has thus become a multi-million dollar international industry. It is estimated that in excess of one billion Valentine cards are sent each year in the United States of America alone.

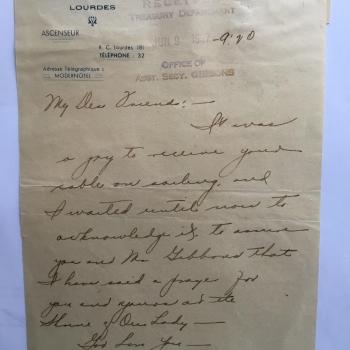

It may not be widely known outside Ireland that the Carmelite Church in Whitefriar Street in Dublin City claims to hold the remains of St Valentine. The Carmelites first arrived in Ireland in 1271, and today there is a community of 17 in the Monastery attached to Whitefriar Street Church. The story of how the remains of St Valentine came to rest in Whitefriar Street is interesting, and involves a famous nineteenth-century Carmelite attached to the Church, Fr John Spratt. Fr Spratt visited Rome in 1835, and apparently largely on the strength of his powers as a preacher, Pope Gregory XVI decided to make his Church a gift of St Valentine’s body, then believed to be in the Cemetery of St Hippolitus in Rome. The remains of Valentine were duly transferred to Whitefriar Street Church in 1836, and since that date have been venerated there, especially around the time of the Saint’s Feast Day.

Want more? Last but not least: you can always check the Catholic Encyclopedia.

Image at top: Saint Valentine of Terni oversees the construction of his basilica at Terni, from a 14th century French manuscript