And he’s written about them both, too. And now U.S. Catholic has a fascinating interview with Jim Forest, discussing Thomas Merton and Dorothy Day — two of my heroes:

Few have written authoritative biographies of the 20th-century spiritual giants Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Worker, and Thomas Merton, the celebrated Trappist monk and writer. Fewer still knew them both. But Jim Forest, a former Catholic Worker himself, did, and his unique insight reveals the human side of two figures many Catholics revere as saints, if as yet uncanonized.

Why the interest in these two people, both dead for decades? “Merton is just a perennial, like certain plants that refuse to stop blooming no matter how many years pass,” says Forest of the monk, who died in 1968, but whose writings are still not all published. “There’s a new book by him coming out every year or two.”

As for Day, with whom Forest lived as a member of her staff, “Her canonization proceedings have gradually made people more and more curious: Who is this Dorothy Day?”

The close friendship between Day and Merton, rooted in their common commitment to nonviolence and the works of mercy, is a fact known to few of their admirers. At heart, they shared a desire to restore to the church its early refusal of violence for any reason.

“If you were to be baptized in the early centuries, you had to make a commitment not to kill anybody, period,” says Forest. “How did we lose that? Merton and Dorothy were two of the people in the 20th century who helped to unpack those boxes that had been pushed up into the attic.”

Dorothy Day lived in New York City among the poor, and Thomas Merton was a monk in rural Kentucky. How did you come to know them both?

When I first came to the Catholic Worker in 1960, I was still in the Navy. I was 19 years old, working at the U.S. Weather Bureau as a young meteorologist and taking kids to Mass on Sunday from a little institution in Washington where I was volunteering in my spare time. I found copies of Dorothy’s newspaper, The Catholic Worker, in the library at this particular parish, Blessed Sacrament, and became curious about the woman. One weekend I went up from Washington to New York to see what the Catholic Worker was all about.

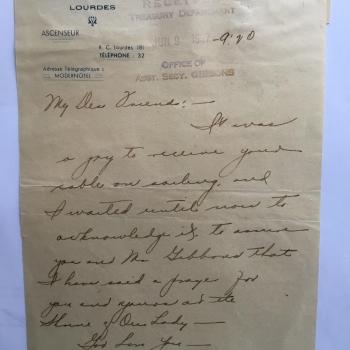

In New York I was given a bag of mail to take to her in Staten Island. She was sitting there with a letter opener at the end of a table with a half dozen people sitting around. One of the rituals of life, as I discovered, was Dorothy reading the mail aloud to whoever happened to be there and telling stories.

One of the letters was from Thomas Merton, and I was absolutely astounded that Dorothy Day, who was very much “in the world,” was corresponding with Thomas Merton, who had left the world with a resounding slam of the door. Of course, they were both members of the Catholic Church and both writers, but Merton had taken the express train out of New York City for good, and Dorothy lived at its very heart.

Dorothy periodically got arrested; Merton certainly did not. Dorothy was very much under a cloud from the point of view of many Catholics because of her anti-war activities, and Merton was regarded as one of the principal Catholic writers in the world. But if they had been brother and sister they couldn’t have been very much closer.

How would you introduce these two figures to someone who doesn’t know them?

I might start with a photo: Dorothy Day between two policemen, awaiting arrest at age 75. It was her last arrest, and you can see that this is a person worth knowing about, somebody who never stopped being disturbed about things that were disturbing, and she did it without hating anybody. She had a gift for seeing injustice and responding without rage but with persistence.

She’s looking at these two policemen like a concerned grandmother of two kids who have their water pistols ready to open fire on grandma—but she’s definitely not in a state of enmity with these two boys and their big guns.

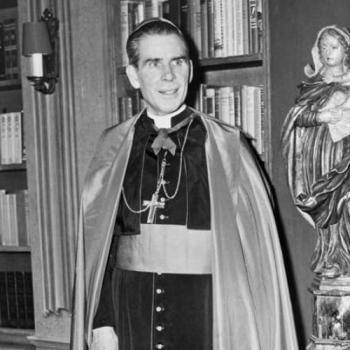

In the case of Merton it’s more difficult because monastic life is so removed. The average age of a monk at Merton’s Abbey of Gethsemani now is 70. Today there aren’t a lot of young people thinking of becoming monks, whereas 50 years ago a lot of people were. I remember when I first saw Merton—there were no author photographs on his books, so you had no idea what he looked like—I sort of imagined some skinny person fasting all hours of the day, certainly not a person with a sense of humor.