Today, in First Things, my mentor, gaffer and friend Elizabeth Scalia does a very gutsy thing. She talks about homosexuality in a way that affirms nobody’s orthodoxy: Wondering whether being born gay might constitute a “call to otherness,” she continues:

I have a theory that our gay brothers and sisters are, in fact, planned, loved-into-being “necessary others,” and that they are meant to show us something of God from a perspective that we cannot otherwise broach. I suspect art is a part of it. I do not presume to guess what attractions Michelangelo felt, but I could not view his stunning work throughout the Vatican and in Rome without recalling a quip someone (I believe Camille Paglia) once made, that when gays were closeted and presumably less active sexually, their energies had been subsumed into creating transcendent, living, time-smashing masterpieces. Now that they were “out”, said the wag, their art was mundane, mostly unmemorable, often lazy and insubstantial.

I know I am entering deep and destructive currents by even daring to swim here, but homosexual questions are all around us—gay marriage, certainly is at the forefront (and there again, we may actually have some instruction from Christ, in Matthew 19) but there is also the issue of recognizing the many homosexuals in our church who are excellent, joyful priests, faithful to their vows and their flocks—and they are questions begging for temperate, reasonable and loving dialogue.

There’s so much good stuff here — where to start? First of all, I really like the idea that eccentricity is no accident. General Patton liked to say that if everybody’s thinking alike, somebody’s not thinking. (Or rather, George C. Scott said that in the biopic; I’m taking it on faith he was quoting the original.) To me, it always seemed self-evidently true that if everyone’s being alike, someone’s not being.

Most Catholic would probably agree. The Public Religion Research Institute reports that “a majority of Catholics supports legal rights for gays and lesbians.” Whatever your own opinion of gay marriage, you’ll allow that those who support it probably believe that gay people: 1) are born gay; and 2) not for no good reason.

But some of the especially devout, I’ve noticed, bind themselves to a much older covenant. Believing homosexuality to be a character flaw, if not a curse, they agree to overlook it until someone wrestles them to the ground and rubs it right in their faces. In this, they believe they’re doing gay people a favor — giving them the benefit of the doubt.

This arrangement produces its comical moments. At my old parish, there was a religious sister who firmly believed that homosexuality was a choice. I’ve never really picked her brain on the subject, but I suppose she believes that gay can be prayed, willed or even married away, the good Lord willing. A friend tells me that one year, a gay parishioner showed up at her birthday party on the arm of, well, a trick — a much younger man, recently acquired, possibly on the street. As the evening wound down, the trick scurried about the room, draining the dregs from everyone’s wine glass while Sister looked on, poleaxed.

Most of her paralysis, I’m sure, came from simple good manners. Few people raised in omes with good china would be able to say, “Hey! Quit minesweeping, you disgusting slob!” with enough force to carry the point. But I’m convinced the imperative to denial, deeply ingrained as it was, played a big part, too. “Leave my glasses alone” would have been one breath away from “Keep your pickups out of my house,” which would have dumped a big jar of nightcrawlers onto the gleaming linoleum of Sister’s worldview.

Call me an unreflective product of my generation, but I think it would have been better for all concerned if Sister had been able to say, “Listen, I know you’re called to be different, but as long as you’re in my house, you’re called to behave like civilized damn human beings!”

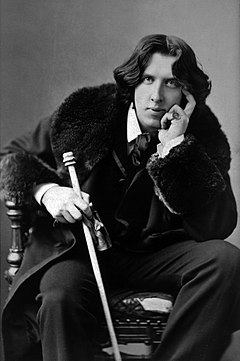

Now onto Elizabeth’s other point, that gays are more productive when most deeply closeted, “and presumably less active sexually” — Oscar Wilde might have agreed. He spoke ruefully of having put his talent into his art and his genius into his life. It’s certainly true that if convention had not obliged him to be a hypocrite, he wouldn’t have been able to speak so profoundly about — and against — hypocrisy, as he did in The Importance of Being Earnest.

But I’m not sure I’m ready to take Wilde completely at his word. He was a vain man, inclined to overlook his own faults — he spends the first part of De Profundis blaming all his misfortunes on Bosie Douglas. Exaggerating the extent to which his work failed to reflect his potential seems to me very much in character.

Even if he were right, would it follow that a sexless life — or a safe one with Constance, Cyril, and Vyvyan at Tite Street– would have provided him more fertile ground for his genius? I doubt it. The mid 1880s, when Wilde’s gay life was at its most dormant — or at any rate, at its tamest — also represented somewhat of a creative doldrums. Wilde’s work took off only later, in tandem with his passions for John Gray and Bosie Douglas. W.H. Auden once wrote that Bosie spurred Wilde’s productivity by presenting him with enormous hotel bills to pay off. Probably. But in The Unmasking of Oscar Wilde, Joseph Pearce points out that Wilde’s work came most to resemble Christian allegory in those times when his life was at its most chaotic. The more he sinned, and courted danger thereby — “feasting with panthers” was his own expression — the better he came to appreciate virtue and redemption, at least in the abstract.

I doubt there’s any single foolproof recipe for creativity — if there is, it would have to include talent, a quality denied even many gay people. But from this one example, it would seem that sex with a sense of sin works at least as well as the sense of sin would by itself.