In the 1990s, a handful of scientists, mathematicians and lawyers launched an organized critique of evolutionary theory that became known as the Intelligent Design (ID) movement. The leaders in this movement included the attorney Phillip Johnson, the biochemist Michael Behe and the mathematician William Dembski.

These experts claimed that there are structures underlying biological organisms, on both the anatomical and molecular level, that are so complex – “irreducibly complex,” as they put it – that the only plausible explanation is that these structures did not arise through the evolutionary process of natural selection but were, instead, planned by an intelligent designer.

The leaders of the movement insisted that they were making a strictly scientific proposal, not a religious one, and that the designer to which they were appealing was not necessarily God. The movement was met with skepticism, even outright hostility, by many scientists, legal professionals and the media who derided it as pseudo-science, even likening the movement to the so-called “creation science” popular among some conservative Christians.

Overview of the Intelligent Design Movement

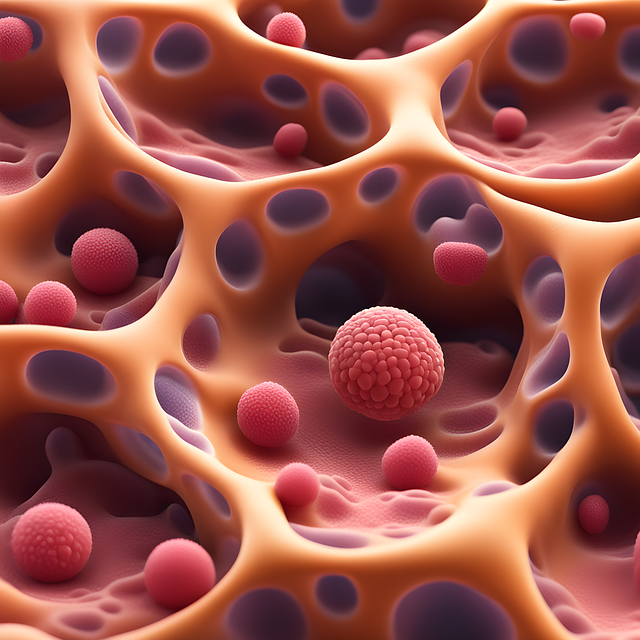

Future historians could date the founding of the ID movement to the encounter in the early 1990s that Phillip Johnson, a University of California professor of law, had with Richard Dawkins’s polemical and bestselling 1987 interpretation of evolution, The Blind Watchmaker. By his own account, Johnson was appalled by the unproven assumptions that undergirded Dawkins’s book and set about, with lawyerly thoroughness, to examine and rebut these assumptions in a series of equally best-selling books, most famously Darwin on Trial (1993). Johnson himself is a lawyer, not a scientist, and he focused his attack on Dawkins and evolution by concentrating on the unproven philosophical assumptions and faulty logic that, he claimed, lie throughout The Blind Watchmaker.

Very soon after Darwin on Trial appeared, however, others joined the ID crusade, including some with scientific credentials. Perhaps most influential was the Catholic biochemist Michael Behe who did his best to provide the scientific ammunition that Johnson lacked in his assault on standard evolutionary theory. In two influential books, Darwin’s Black Box: The Biochemical Challenge to Evolution (1996) and The Edge of Evolution (2007), Behe attempted to provide a theoretical framework for the claim that the theory of unguided evolution does not, and even cannot, explain all of the complex biological phenomena in nature. Behe was joined by the mathematician William Dembski and together they developed a positive vision of a scientific alternative to standard evolutionary theory which they called Intelligent Design. Although Behe is a Catholic and Dembski Eastern Orthodox, not all proponents of ID are religious. Some of those open to ID arguments, such as the atheist philosopher Thomas Nagel, are impressed by the philosophical criticisms that ID presents. What’s more, ID proponents such as Behe go out of their way to stress that ID is a scientific movement, a criticism of standard evolutionary theory from within science itself.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Intelligent Design was championed by the Discovery Institute in Seattle and by some conservative and evangelical political organizations. These sought to pressure local school boards to include ID ideas and materials as part of the teaching of evolution in schools. This led to a famous court case in 2005, reminiscent of the original Scopes Monkey Trial, in which a conservative judge and practicing Lutheran ruled that ID could not be taught in schools because it is “not science,” fails to meet the requirements that “limit science to testable, natural explanations” and constitutes an attempt to impermissibly advance a particular religious viewpoint.

At the center of ID’s critique of standard evolutionary theory lies the concept of “irreducible complexity.” According to Behe, there are entities within biological systems that are so complex that they could not have evolved through the normal pathways of evolution, that is, through random genetic mutations and natural selection. Among the entities that Behe cites are the bacterial flagella, blood clotting and the elaborate assemblies of protein molecules that appear, within cells, like “an elaborate network of interlocking assembly lines.”

In Darwin’s Black Box, Behe defined an irreducibly complex system as “a single system composed of several well-matched, interacting parts that contribute to the basic function, wherein the removal of any one of the parts causes the system to effectively cease functioning.” He adds that such a system “cannot be produced directly… by slight, successive modifications of a precursor system, because any precursor to an irreducibly complex system that is missing a part is by definition non-functional. In other words, for Behe an irreducibly complex system has parts that have no other functions than those of that particular system and which are essential to that system.

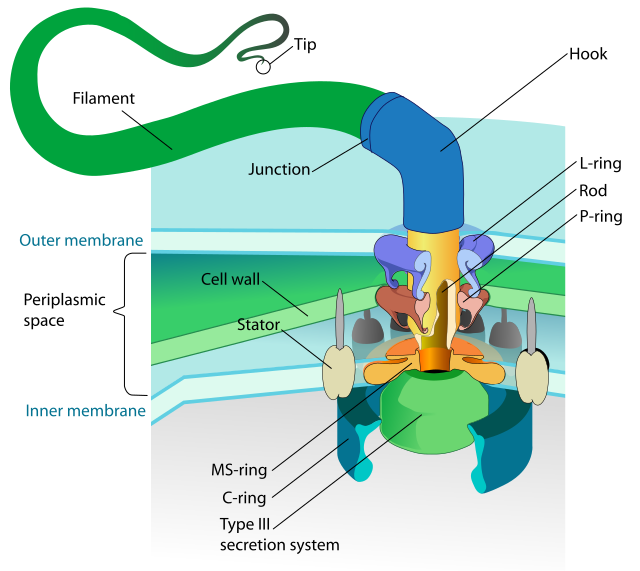

Behe points to the bacterial flagellum as an example.

The flagellum is a kind of microscopic propeller system used by different types of bacteria for propulsion. As Behe explains, it consists of a long, hair-like filament embedded in the cell membranes that is attached to a rotor drive. Powerful electron microscopes have revealed that this rotor drive is powered by energy produced by ion exchange through a flow of acid into the bacterial membrane and which turns the filament like a propeller. Behe claims that the three parts that make up the flagellum – a paddle, rotor and motor – show that it is irreducibly complex. “Gradual evolution of the flagellum… therefore faces mammoth hurdles,” he writes, by which he means it almost certainly was designed, not evolved through small, incremental changes over billions of years. “Even though we are told that all biology must be seen through the lens of evolution, no scientist has ever published a model to account for the gradual evolution of this extraordinary molecular machine,” Behe writes.

Denis Alexander’s Criticisms of Intelligent Design

Sophisticated ID advocates like Behe concede that the natural selection mechanism proposed by standard evolutionary theory provides reasonable explanations for some complex systems, just not for others – such as the bacterial flagellum. Behe agrees that evolution can explain biological complexity in principle and merely argues that we have no evidence for how it could do so in specific cases. According to critics of ID like the Christian biochemist Denis Alexander, however, the problem with arguments like this – so-called arguments from ignorance – is that new information has a way of popping up unexpectedly and ruining your case. For example, Alexander argues that scientists have discovered that some of the parts that make up the flagellum do have functions in other organisms, such as the ion exchange energy system that powers the flagellum filament. This seems to undercut the perception of design in this case because this part is not unique to the flagellum.

Alexander makes the same criticism for another example of an irreducibly complex system that Behe proposes: blood clotting. In Darwin’s Black Box, Behe argues that the complex biochemical system that is blood clotting – the way the body forms blood clots to stop bleeding when someone cuts his or her finger, for example – is irreducibly complex. Behe describes in great, professional detail the myriad steps that go into forming blood clots – how proteins called Hageman factor stick to cells near a wound, and then another protein called HMK activates the first proteins to turn another protein, called pre-kallikrein, into kallikrein, which then starts a whole chain reaction of complex biochemical transformations that result in the attraction of sticky platelets that flow through a wound and eventually congeal into a plug that stops the bleeding. It’s an unbelievably complex, delicately balanced process involving a “menagerie of biochemicals” that Behe likens to a Rube Goldberg machine and before which, he says, “Darwinian theory falls silent.” What Behe means by this is that biologists have no explanation for how such a clotting mechanism could have gradually arisen through incremental, evolutionary steps.

Alexander’s reply is that this is simply incorrect. In fact, he claims that an evolutionary mechanism could explain how blood clotting arose “quite easily.” The details are difficult for a non-expert to follow, but in essence Alexander argues that all that is required to show an evolutionary pathway is to find simpler blood clotting systems in other animals from which larger animals evolved – for example, starfish.

Starfish, apparently, also have platelets that “become sticky, bind to other proteins like collagen, and block a further escape of blood.” What Alexander claims is that the various “parts” that make up the complex blood clotting systems in vertebrate species such as humans can be found in other creatures and therefore illustrate how “multi-component systems can assemble by Darwinian mechanisms.” In other words, the super-complex blood clotting system in humans may look custom-made but has been around, in simpler forms, for 400 million years. For Alexander, this means that variations on this system could have arisen through natural selection and the ones that worked best, and which aided survival, endured and were passed on to human beings.

Alexander’s larger point is that ID is just another example of “God of the gaps” arguments – or, in this case, “designer of the gaps.” If science has no explanation for how a particular biological system developed, proponents of ID claim that it’s “irreducibly complex” and a designer must have planned it. This was how, he says, many people in a pre-scientific age proposed to explain such mysteries as the movement of the stars or the bubonic plague.

“Though each supposedly ‘irreducibly complex’ system is proposed by ID proponents as being, in principle, inexplicable by normal evolutionary mechanisms, all we need to do is wait a decade or two, often less, and a coherent evolutionary account begins to emerge,” Alexander claims. Science advanced when both scientists and churchmen decided that God is the “author of the whole created order” and that it is the job of scientists to figure out how that order works from the astronomical to subatomic levels. In other words, Alexander argues that ID lets scientists off the hook and cease seeking the details of God’s creation, simply asserting that something is “irreducibly complex” and a “designer made it.”

Behe has replied, at length, to some criticisms of intelligent design. He is particularly forceful in rebutting scientific criticisms, since that is, after all, his area of expertise. In a 2001 article in the journal Biology and Philosophy, Behe answered some scientific criticisms point by point, for example insisting that a biochemist who claimed that blood clotting can be explained through natural selection misunderstood the relevant literature. Without getting bogged down in such scientific details, Behe’s main response is that many scientists agree that some biochemical systems have, as yet, no credible evolutionary account of their origin, and that therefore it is an open question whether his hypothesis of “irreducible complexity” is viable.

As for the larger philosophical criticism that intelligent design is merely a “God of the gaps” argument, attributing intelligent design to a system that simply has yet to be explained and thereby stifling rather than advancing scientific inquiry, Behe is less convincing. On the one hand, he insists that God has nothing to do with his hypothesis since the designer he proposes could be entirely natural, such as a super-intelligent alien race. Behe also argues that his analysis is based on empirical evidence and basic logic and therefore should be deemed scientific on that basis. He is, he claims, merely advancing an alternative scientific hypothesis.

This did not convince Judge John E. Jones III, the district court jurist who ruled against the teaching of ID concepts in the Dover, Pennsylvania, school district, who declared that ID impermissibly advanced a religious viewpoint in a public school setting. In his 2005 opinion, Judge Jones claimed that ID did not meet the standards of peer-reviewed scientific research. “To be sure, Darwin’s theory of evolution is imperfect,” the judge declared. “However, the fact that a scientific theory cannot yet render an explanation on every point should not be used as a pretext to thrust an untestable alternative hypothesis grounded in religion into the science classroom or to misrepresent well-established scientific propositions (Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, 2005: 765).”

Alvin Plantinga Critiques Uncritical Assumptions

In his 2011 book Where the Conflict Really Lies, the Christian philosopher Alvin Plantinga also looks at the ID movement in general and at Behe’s biological arguments in particular. After noting what can only be described as the hysterical reactions to Behe’s proposals from some members of the supposedly detached scientific community – one scientist labeling Behe’s views “silly, lazy, ignorant and intellectually abominable” – Plantinga first analyzes the central assumptions that underlie Behe’s project. The problem with some of the scientific critics, Plantinga says, is that they seem to suffer from “an inability to pay attention to what Behe actually says.” For example, in his book, The Edge of Evolution, Behe spends considerable time discussing the intricate “protein machines” that make the life of cells possible. He believes that some of these structures are so complex, they exhibit signs of intelligent design. Yet rather than discuss the specifics of cellular biology that Behe brings up, critics such as Richard Dawkins lapse into their usual ad hominin attacks and, in Dawkins’s case, digressions about the artificial breeding of dogs.

Plantinga’s analysis is more substantive. For example, he takes aim at Behe’s use of probability theory to buttress his case. One of Behe’s arguments for intelligent design is the relative paucity of mutations seen in microbiology. This lack of mutations is significant, he believes, because standard evolutionary theory requires mutations for natural selection to have anything to, well, select. Behe points to widespread diseases such as malaria and HIV and notes that, despite astronomical numbers of disease organisms coming to exist over the past century, and a wholesale assault upon them by the pharmaceutical industry, there have been no known mutations identified. After 50 years of malaria drugs and a hundred billion billion malaria bacteria – that is, 1020 individuals – no mutations exist, Behe claims. Somehow this suggests to Behe that the complex protein machines within individual cells could not be the result of random mutations guided by natural selection but, rather, the result of intricate planning on the part of a designer.

Plantinga objects that improbable things happen all the time, and that throwing around big numbers like this actually proves very little. The odds of having a particular hand in Bridge, he says, is equally astronomical, something on the order of 10.-112,000 When it comes to cellular protein machines, how can we rationally evaluate the probabilities of unguided evolution versus an intelligent designer? As he often does, Plangtina argues that there is no way to calculate credible probabilities in either scenario. The situation simply does not allow for realistic probability calculations and so, he says, “it is unclear that the difference in probability is sufficient to constitute serious support for the existence of an intelligent designer.”

Of course, Plantinga, one of the most famous Christian philosophers of the past thirty years, believes that the universe was ultimately created by an intelligent designer. The issue is not this philosophical claim but whether scientific methods can, using such tools as probability theory, make a convincing case for a designer on scientific grounds. For this reason, Plantinga distinguishes between design arguments, typical of natural theology, and what he calls design discourses. A design argument proceeds from premises to a conclusion, and comes in various forms – arguments from analogy, from induction, from an inference to the best explanation. Design discourses, on the other hand, are less arguments from premises than they are statements of perception: they reflect an awareness of complexity that points to, or suggests, design. Like all perceptual beliefs formed in a basic way, such design discourses are not infallible; they are subject to being rebutted by “defeaters,” other beliefs that are logically contradictory to what is being asserted.

Plantinga is intrigued by Behe’s design discourses, his perception of “irreducible complexity” in various biological structures, but not convinced. “Behe’s design discourses do not constitute irrefragable arguments for theism,” he says. Neither, of course, are such critics as Dawkins: “If correct, Behe’s calculations would at a stroke confound generations of mathematical geneticists, who have repeatedly shown that evolutionary rates are not limited by mutation,” Dawkins concludes in his 2007 review of The Edge of Evolution, with an Oxbridge sneer at Behe’s lesser academic credentials. “Michael Behe, the disowned biochemist of Lehigh University, is the only one who has done his sums right.”

However, Plantinga argues that just because Behe hasn’t proven, mathematically or otherwise, that complex biological structures are designed it does not follow logically, as critics such as Dawkins mistakenly believe, that the converse is true: that it is proven that the universe has not been designed. To make this point Plantinga introduces the concept, common in philosophy but not in science, of a “defeater” for an inductive belief. A defeater is a belief that either undercuts another belief or, in some cases, effectively rebuts it so that it would be logically impossible to hold the defeater belief while holding the other. Plantinga points out that just as Darwin is wrongly believed to have provided a rebutting defeater to William Paley’s original design argument for God, so, too, critics such as Dawkins and the philosopher Daniel Dennett wrongly assume that today’s evolutionary theory provides a rebutting defeater for intelligent design arguments such as Behe’s. But both conclusions are false and overstep the evidence, according to Plantinga. In fact, he calls such arguments “unsound in excelsis.”

Plantinga asserts that these critics simply assume without argument that “current evolutionary theory includes the proposition that the process of evolution has not been guided (by God or anyone else), despite the fact that this proposition looks much more like a metaphysical or theological add-on than part of the scientific theory as such.” Indeed, Judge Jones made the identical point in Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, although it received little attention in the media. Because one of the motivations for introducing ID concepts into school curricula was the allegedly anti-religious tenor of standard textbooks about evolution, Jones emphasized the testimony from numerous scientific experts that the theory of evolution, properly understood, does not refute theistic belief, as is sometimes thought. “Both Defendants and many of the leading proponents of ID make a bedrock assumption which is utterly false,” Judge Jones concluded. “Their presupposition is that evolutionary theory is antithetical to a belief in the existence of a supreme being and to religion in general. Repeatedly in this trial, Plaintiffs’ scientific experts testified that the theory of evolution represents good science, is overwhelmingly accepted by the scientific community, and that it in no way conflicts with, nor does it deny, the existence of a divine creator (Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, 2005: 765, emphasis added).”

What Intelligent Design Gets Right

The upshot from all of this is that the ID movement arose from a dissatisfaction at the unproven philosophical conclusions that some proponents of standard evolutionary theory, such as Richard Dawkins, loudly express, and at legitimate questions that some scientists have about the inability of current evolutionary theory to explain some complex phenomena. Unfortunately, the alternative scientific hypotheses that the scientific members of the ID movement have proposed – such as the concept of irreducible complexity – appear to have been largely rejected by the scientific community. Moreover, some factual claims of the ID movement – for example, that there are no evolutionary explanations for some biological systems — are disputed by experts.

Yet the larger point motivating the ID movement seems legitimate: that there exist complexities in biological structures, what Plantinga calls design discourses, that cry out for explanations that current evolutionary theory has yet to provide.

In addition, some (not all) proponents of evolutionary theory draw conclusions far beyond what the evidence allows and wrongly conclude, as Judge Jones pointed out, that evolutionary theory proves that science is “antithetical to a belief in the existence of a supreme being.” The overall conclusion that one might draw from this controversy, therefore, is that science works bests when it avoids being tangled up in larger philosophical debates that are outside of its competence and concentrates, instead, on studying the mechanisms and processes that make up the natural world. This holds true both for atheists such as Richard Dawkins – whose vituperative polemics against theistic belief gave rise to the ID movement — and for theists such as Michael Behe.

Robert J. Hutchinson is an award-winning Catholic writer who writes about the intersection of ideas and politics. He is the author of numerous books of popular history, including Searching for Jesus: New Discoveries in the Quest for Jesus of Nazareth (Thomas Nelson), The Dawn of Christianity (Thomas Nelson), The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Bible (Regnery) and When in Rome: A Journal of Life in Vatican City (Doubleday). You can contact him at his website, www.DisputedQuestions.com.

Robert J. Hutchinson is an award-winning Catholic writer who writes about the intersection of ideas and politics. He is the author of numerous books of popular history, including Searching for Jesus: New Discoveries in the Quest for Jesus of Nazareth (Thomas Nelson), The Dawn of Christianity (Thomas Nelson), The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Bible (Regnery) and When in Rome: A Journal of Life in Vatican City (Doubleday). You can contact him at his website, www.DisputedQuestions.com.