I’ve been thinking a lot about my mom these days anyway, since it has been nearly thirty-three years to the day since I last saw her. And then I read this article: “Not Your Mother’s Morals”: A Review.

I’ve been thinking a lot about my mom these days anyway, since it has been nearly thirty-three years to the day since I last saw her. And then I read this article: “Not Your Mother’s Morals”: A Review.

And let me say up front, this post is no reflection on Jonathan Fitzgerald, his mother’s morals, his position on his mother’s morals, or his thoughts about your mother’s morals. This is not a comment about his book, which I have not read. This is simply a visceral reaction to the review, and the reviewer’s argument about the meaning of the book for Christian life today. By all means, buy the book. I’m sure it will be good.

One reason I really should not be responding in any way, shape, or form is the subtitle of his book—How the New Sincerity Is Changing Pop Culture for the Better. The Lord knows, my children know, my colleagues know, and you probably know that I can barely spell pop culture. My ignorance about the latest television shows, novels, music trends, and most movies is a deep, deep abyss. From what I do know about it, I’m rather glad to hear it’s changing for the better. I know just enough about such things to know that if it’s a Tarantino movie, I don’t want to see it; and if it involves a Korean music artist fake-riding a horse, I’m a dolt; and if it’s not a ten-year-old rerun of “Everybody Loves Raymond,” I probably haven’t seen it. This is not bragging; this is confessing, with some measure of embarrassment, because I truly believe the Lord is interested and involved in pop culture and what it does to and for people. I simply don’t have it in me. Call me a pop-culture philistine, but I’m a sincere philistine.

So back to my mother. And her morals.

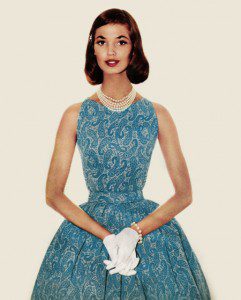

My mother was most certainly a product of her own culture, one that most of you would call fundamentalist. If I tell you she went to Bob Jones Academy, boarding there through her high school years, that will tell you something. She had all the “baggage” associated with a lot of fundamentalism: a narrow moral code (forget things like premarital sex or alcohol or dancing or smoking, and move on to really wicked things—no movies, no fingernail polish, no playing cards, no bowling); a normalized Dispensationalist outlook; a genteel white poverty borne within a restricted community of the like-minded. The most radical thing she did as a young person was marry my dad, who was a Wheaton guy.

But my mother was the embodiment of sincerity. She was joyfully, consistently, and freely what she was—centered in patterns of old-school traditionalism, yet happily stretching the boundaries as life so required.

The reviewer writes: “The perfect example of the New Sincerity at work is the hugely popular band Mumford & Sons. As Fitzgerald talks about in his Patrol piece, “Mumford and Sons Reviewers: You’re Doing it Wrong”, they have strong spiritual themes on the album, but unlike sanitized bands of Christian Contemporary music of the past, they don’t stuff their lyrics with a certain number of “Jesus’” and they don’t shy away from questions, feelings of despair, or even a few couple of F-words.”

Shall we assume, then, that those whose music is “sanitized” by being F-word-free are less sincere? Less authentic? Less free? Are we freed by displaying our angst and our doubts? Is sincerity tied to lack of restraint? Is sincerity really all about me?

While I realize, I really do, that many who grew up in fundamentalist or severely conservative homes found their lives tightly controlled to the point they couldn’t even breathe a human breath, this is a stereotype; and yes, stereotypes become stereotypes because they have a track record for being accurate. However, the message here is that those who have a morality that includes unsalted language, a personal reserve about airing deeper issues of fear and despair in public, and a deep reluctance to coddle the coarser aspects of their personalities are hopelessly stuck in mental cages, where they pace their 10-foot-by-10-foot worldviews and snarl at the free people who pass them in the streets, glibly and liberally airing their darker passions and publically exploring the limits of their moral choices.

The reviewer writes: “Today in society we are bringing these two worlds together because after years of singing Jesus-is-my-boyfriend worship tunes and putting on our Good Church Goer personas every Sunday, we long to be in a world where the spiritual is not allergic to the messiness of humanity, but embraces it and is a part of it.”

My mother would never, never have sung a Jesus-is-my-boyfriend song—she couldn’t even really bring herself to sing “Jesus, Lover of My Soul” because of its, well, lover-language. Lurid connotations, you know. But my, oh my, she had the Good Church Goer persona down to a science. She was, after all, the pastor’s wife, and from all reports, there were few better. But this is really who she was. Head to toe, inside and out; she wasn’t “stuffing” her true self so that she could people-please. This was her true self. And her true self fully embraced the messiness of humanity with kindness, with decorum, with quiet Christian gentleness, and with an iron core of self-discipline. Aching inside from some personal grief or frustration, she could go to church on Sunday morning, put on a gracious smile, greet people warmly and cheerfully, and yet not at all be depressed, repressed, or suppressed. This, in the Old Sincerity, is called self-denial, which used to be a virtue and a strength.

The reviewer writes: “When you [let] people create the art their souls ache for, their humanity and hearts emerge, which are messy. This is why the New Sincerity is making some people uncomfortable; because it’s making us come to terms with all sides of ourselves, including some of the scarier ones like doubt, anguish, and a loss of answers.”

My mother knew all about doubt, anguish, and the absence of answers. She knew grief and discord, anxiety and frustration, pain and fear. She had hang-ups, faults, personal indulgences, and secret disappointments—I’m not writing a hagiography here. But she shied away from nothing that the Lord gave her, including her own suffering and death. She simply did not need to broadcast her internal experiences in order to cope with them. Her generally conservative hermeneutic of scripture, culture, life, and love was not a false self, a deluded self, a June-Cleaver-cut-out self, but a thoroughly authentic and rich pursuit of quiet, disciplined godliness.

After all, sincerity is not really the point. Lots of sincerely nasty and naughty people are out there who have crafted a morality, picking and choosing moral values that suit their internal compass just fine. (Of course, the ancient Christian message about the unreliability of our internal compasses does tend to make us uncomfortable.) The question is, for New Sincerity or Old, what fruit does it bear? What is the point of morality, yours or your mother’s? My mother’s morality gave birth to boundless energy for church life, a ferocious work ethic, a spirit of generosity and hospitality, and, well, a laugh that could bring down the house. Tradition merely created the scaffolding upon which she built a life characterized by the g-word (gentleness), the h-word (hopefulness), and the f-word (faithfulness).

Here’s to Our Mothers’ Morality.

Update: Yes, this post has now exposed me to my children’s commentary on their mother’s morals. I doubt I will fare as well as my mother did. But then, I’m not finished yet. I can still, and always, pray for the grace of true repentance and the Holy Spirit to amend my life. I’m sure my kids would like that.