On Trinity Sunday, many preachers across the country gently and respectfully work their way around actual teaching about the Trinity—as though it were some kind of large embarrassing object in the road—and move on to a topic more user-friendly.

This may seem to be the better part of wisdom, since we can’t “figure it out”; we believe in one God, yet we talk about Three—Father, Son, Spirit—and 1+1+1=1 just doesn’t compute; it’s hard to talk about; so… let’s just not.

Really, the doctrine of the Trinity: Isn’t it just one of those obscure theological niceties that seminary students have to figure out? After all the word “Trinity” isn’t even in the Bible. We have to ask: Is it necessary? Is it helpful? Is it meaningful?

We all check the Trinitarian box in our list of important doctrines to believe, but we rarely, if ever, take our belief in the Trinity out to examine it. Keep it simple, baby. Maybe I’ll need that doctrine someday; maybe I won’t. But when I get to those pearly gates, I can pull it out and demonstrate that yes, indeed, I “believed” that… see, I signed here… no, I never really thought about it much… it made my head hurt.

Yet without solid teaching about the Trinity, we are all too often left with old Sunday School images: three-leaf shamrock, water-ice-steam, family roles (e.g., I am a daughter, wife, and mother all at the same time), heat-flame-light, etc.—all of which are not only inadequate, they’re diminishing and even detrimental as we grow in faith.

One big problem with such models is that they’re so easy: I say, “Of course I believe in the Trinity,” and have a shamrock or some other image in my head, and then feel like I’ve got that doctrinal emergency kit in the trunk. After all, certain doctrines just need to be packed away and hauled through life, like equipment you might need someday on the journey, just in case…

So why preach on it? Because contemplating (and I’m using that word intentionally) the Trinity can draw us all more fully into a rich, joyful, relationship with God. It is the fullness of God’s invitation to us.

A friend once commented to me that thinking about the Trinity is like getting too close to an Event Horizon, the boundary marking the limits of a black hole, that liminal space where, if light (or anything else) crosses it, it cannot escape. I think he meant it as a warning, but it should be a great encouragement, the hope of a great joy.

In this sermon, I want to do three things, none of which involve “explaining” the Trinity. They may, I hope, provide some guidance around how to pursue a deeper enjoyment of God:

- First, I’ll make some brief comments about Church history, so that we can dispel some popular myths.

- Second, let’s consider together why the Trinity is the key to the Gospel, and what it means to believe in the Trinity.

- Third, we’ll give some thought to ways of growing in our love for the Trinity.

Historical Reflections

It is a glorious truth that we embrace a Reality that is not subject to the limits of human reason. Do you really want to worship a God you understand completely? The early church would have had a much more marketable and acceptable religion if it had reduced Christian truth to more manageable and palatable dimensions, which do not include a crucified God or a monotheism that involves Three Persons.

The experience of the church in its first centuries began the same way as the disciples’ experience did—by encountering Jesus. The gospel spread because of the message about Jesus crucified and raised. Evangelism did not begin with the Trinity; it began with Jesus.

The same is true today. No one needs to wrestle with the doctrine of the Trinity in order to come into relationship with God in Christ. We need to see Jesus. However, the early church found that, once we do see Jesus—when we really see him for who he is, fall at his feet and worship him as immeasurably worthy and realize what he is doing in this world and through the Church—then the mysteries begin to roll over one another, deeper and deeper.

The early church understood this process of entering into the cascading mysteries of the faith. They only taught these things after baptism because these are things that can only be approached on the near side of faith, as it were. The teaching of the Trinity is not something that can be explored meaningfully without faith; it is a kind of query that involves mind and heart and soul.

When we come to Jesus, we receive baptism—a new identity—and our Trinitarian language informs this act of transformation: We baptize you in the Name (one name) of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit. Then we, just as the early believers did, explore the scriptures more deeply and we learn even deeper truths about this God who is our very Life.

The Church in faith recognized the Trinity in the Annunciation, the baptism of our Lord, the Transfiguration, Jesus’ Great Commission. Here, for example, is one representation of the Trinity at work in Jesus. This is Pietro Perugino’s “Baptism of Jesus Christ,” painted in 1481. Here we can see the Three and the way that the artist lines them up in a single trajectory; as the Son takes on the mission of redemption, the Father affirms his Beloved and the Spirit descends. The Three Persons are not independent; not separate; not autonomous: “We believe in one God.”

As early believers encountered God in Jesus and examined the scriptures, more and more they understood that something complex and mysterious and too wonderful for our understanding was going on; they experienced the revelation of Jesus illuminating all of salvation history, from Genesis forward. One of the earliest Trinitarian readings of the Hebrew scriptures was the Hospitality of Abraham to the Three Visitors (Genesis 18). Here we see a sixth-century mosaic depiction of this. It can be found in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy.

Still, in the first centuries of persecution they had not developed a vocabulary around this mystery; only with Emperor Constantine’s conversion and his Edict (in 313) that legitimized the Christian faith did the Church recognize that with its new public profile, it must take up the task of presenting the Christian faith to the world in a way that clearly and competently taught truth. It’s hard to articulate and work on theological ideas when you’re running for your lives.

Christianity was taking its place in a pluralist world (not unlike ours), where multiple religions and philosophies and lifestyles ran rampant. Polytheism was the norm; monotheism was a Jewish peculiarity. Christianity was adamant that it was part of the Jewish story. How was Christianity going to present itself in a marketplace of ideas like that?

The questions generated heresies, as they often do, not primarily because there were malicious sneaks in the Church, but because the questions had not been adequately considered. They were big questions: we are monotheists, we believe in one God; but then who exactly is Jesus and why do we worship him? And why does Jesus talk about the Holy Spirit as though he were someone else? And how does the Father send the Son? If, they said, we’re going to teach that we are monotheists and we’re going to teach that Jesus Christ is Lord, we are going to have to come to some way of understanding it ourselves.

Church members came up with multiple ways to satisfy the conundrum, all of which the church weighed and found inadequate; we call them heresies, and they come in an abundant variety. Yet every heresy that has ever wormed its way into Christian discourse is a reduction of the great gospel. Every heresy is a human management system trying to pin down Christian faith and practice in ways that try to satisfy our priorities, lessen the grace, box God in, close the possibilities, control faith, reduce the glory and mystery and power of who God is, what God has done, and where God is taking us. Traditional Church teaching is always far more liberating—bigger, grander, deeper, and richer—than any heresy.

The Nicene Creed (325, 381), was the Church’s summary of Trinitarian thought—embedding in the Three-in-Oneness all of creation, incarnation, Passion, resurrection, and Spirit-filled community. It was the result of discernment and an unyielding adherence to scripture and the experience of the Church; it was not the decision of a church council, despite the Dan Browns and Da Vinci Code conspiracy novels of the world. No one “came up” with the idea to make Jesus divine or concocted the idea of the Trinity because it was an advantageous idea to promote; rather, it was the accumulated experience of the people of God; it was the way they worshiped and believed from the day of the Resurrection forward.

The Trinity and the Gospel

The doctrine of the Trinity is not extraneous or supplementary or an obscure appendage to the Christian faith. It is the heart of the Gospel.

In thinking about these things, 4th-century theologian Augustine began with Love, for we know that God Is Love (1 Jn 4.8). He doesn’t merely have love or show love. He is love. Augustine understood that love essentially requires relationship. Love is not love unless there is someone who loves and someone who is loved. Love does not exist in a vacuum. There is no such thing as generic “love.” If God is Love itself, then we can conclude that God is and always has been intrinsically relational. Apart from us, before we existed, before all that is was created, God was already Love and has always been Love.

Augustine understood that the very nature of God reveals a Lover and a Beloved. And, because the Love that extends between the two is divine, that Love itself is personal, distinct, named—Spirit. Lover, Beloved, Love. Love given, Love received, Love exchanged. The Three moving as in a dance, ever-giving, ever-receiving Love between them; as Augustine put it: “They are each in each and all in each and each in all and all in all and all are one.”

Note the way that Greek artist Theophanes Bathas depicts this union (late 16th c.). Father and Son are shown in shared motion, shared vision, shared communication, with the Spirit moving between them. Note the gospel in Jesus’ hand. This one God reaches out to us with the Word of truth—about God, about us, about the world we live in, past, present, and future; the Gospel is the message of the Trinity.

We cannot begin to understand the glory of the Incarnation or the Atonement, the Crucifixion or the Resurrection or the Ascension or Pentecost without the foundation of the Trinity. In the words of one scholar, “The Trinity is the space within which the Christian life takes place.”

In thinking about the life of Jesus poured out for us, early Christians began to understand that God is by nature self-giving; God loves, eternally, and gives himself eternally within the Godhead—Father to Son, Son to Father, the Spirit to the Father and Son. The Gospel is the story of this self-giving God giving himself to and for us.

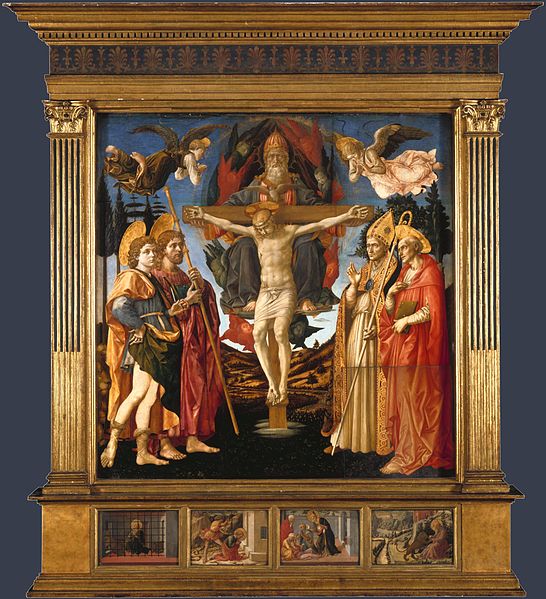

Francesco Pesallino’s “Holy Trinity” (1455), shows the Threeness of the Crucifixion; all three Persons of the one God are involved in the gift of God to redeem humanity and draw us to himself. This dispels some of the weirdness around broken concepts of the atonement that divide the Father from the Son on the cross.

This Love-poured-out is the meaning and purpose of creation, redemption, and sanctification. It is the origin and destiny of our existence. It expresses the very identity of God: God is doing what he is. God is both the One who loves and the Beloved who loves in return; in the deep purposes of God, he creates, loves, redeems, and invites us to love in return.

Trinitarian spirituality

Now we draw on fourth-century Greek theologian, Gregory of Nyssa, who was involved in the writing of the Nicene Creed. Gregory wrote eloquently about the tension we experience between our desire—indeed our need—to know God and our limited, finite understanding. We must know God and love him—it’s our whole purpose—but God is too big and mysterious for our finite minds. How do we resolve this tension?

Gregory addressed this by talking about the problem of our idea of knowing something as a way of grasping, like your hand enclosing completely the object. This kind of knowing is the way we know the Rockies’ sad score at the end of the 12th inning in Friday night’s game or the way we know the name of the governor of Colorado or the way we know what county we live in. Gregory suggested instead that we explore a way of knowing that is dynamic, in motion, a way of “approaching” or “traveling” in the direction of the object to be known. It is a kind of quest. This kind of knowing is like getting married. You “know” who’s standing there at the altar with you, but you really don’t. And that knowledge never ceases to grow. It’s dynamic. It “travels.” It expands.

This makes all kinds of sense to me. Even in all this exploration of Trinitarian language and belief, as enriching and meaningful as it is, I recognize deep inside that we’re only scratching the surface here. The depth of the Triune God cannot be captured by our creeds, our formula, or our human language, which is finite, material, limited. But I do believe that Trinitarian faith is believing in the right direction. We’re moving in the direction of truth, even if we cannot grasp its fullness.

One scholar calls this the “limitless horizon” of faith—meaning that our understanding and trust can never grasp the fullness of God, they can only keep moving in the direction of that truth. The horizon of God always extends itself infinitely before us. “This inexhaustible plenitude of God”—the never-ending, infinite depth and breadth of the reality of God’s being—is the invitation to an “endless journey” of relationship. All our doctrines, true as they may be, are meant to be “stepping stones” of discovery.

Contemplating the Trinity—loving the Triune God—demands a dynamic movement toward him, a growth in faith and love. And as we stumble our way forward in this yearning to understand what we cannot understand, we are transformed. It’s like the description of the real Narnia that we read of in C.S. Lewis’ The Last Battle: “The further up and the further in you go, the bigger everything gets. The inside is larger than the outside.” What is the constant call and invitation in that magical place? “Don’t stop! Further up and further in!”

Here are some ways you can grow in the love and knowledge of the Holy Trinity.

- As you read the Bible, read it all as the activity of the Three-in-One God. Look for the Father, the Son, and the Spirit in the whole work of Creation, the calling of Israel, Incarnation, Lordship, Passion, Death, Resurrection, Ascension, life of the Church, and the eternal future. Read the scriptures and see the Three-in-One active in the whole story of our salvation. God giving endlessly of himself.

In this picture of a carving from the Basilica of Saint Denis (12th c.), I love the way the Father is offering the Lamb of God and the Holy Spirit hovers over the giving. In looking for the Three, we will love the One True God.

- Consider the ways we worship, the ritualized language, the hymns, the prayers, etc. Listen, really listen, to the prayers we pray together. Think of worship as a multidimensional experience of God in which you enter into the life of the Trinity through Christ. True knowledge of God ALWAYS leads to worship. If you think you can know God without falling down in adoration, you’re mistaken.

- Nurture your relationship with Christ: We enter into the life of the Trinity through Jesus Christ; he is the Way, the Truth, and the Life. Paul uses the phrase “in Christ” (or related forms) 165 times in 13 letters. This isn’t just odd Greek language, but a reference to the mystical experience of being incorporated into the life of God in the person of the incarnate Son.

Julian of Norwich understood this when she wrote:

Suddenly the Trinity completely filled my heart with the greatest joy. And so, I understood, it will be in heaven, without an end, for those who come there. For the Trinity is God; God is the Trinity. The Trinity is our maker. The Trinity is our keeper. The Trinity is our everlasting lover. The Trinity is our endless joy and our bliss, through our Lord Jesus Christ and in our Lord Jesus Christ. … For where Jesus appears, the blessed Trinity is understood.”

One last image, perhaps the most famous depiction of the Trinity.

This is Andrei Rublev’s 14th century icon. Here we see one God in the union of the Three; the Father on the left, as both Son and Spirit look to and love him. The mansion behind him reminds us of Jesus’ promise: “In my Father’s house are many mansions.” The Son is in the middle, garbed in brown, the color of earth. Behind him we see the tree, representing both the Tree on which he hung and the Tree of life which he became. The Spirit is on the right, robed in pale green, the color of life. The mountain behind him represents that place where heaven and earth come together, the place, every place, that we encounter God.

“Trying to understand the Trinity is like a physicist getting too close to an Event Horizon: it will suck you in.” Exactly!! As long as we want to study God objectively, dissect its parts, and manipulate the data, we had darn well better stay at a safe distance. But if we want to see the face of God, if we long for a richer, fuller, more glorious relationship with our Lord, if we want to be filled with the Spirit, then let us contemplate the Trinity and adore him.

I encourage us all today, let’s get closer; let’s get sucked in. Amen.

For those interested in greater exploration of some of these ideas, consider reading my earlier series on the Trinity. Here is the introduction.

Elephant Photo by Magda Ehlers from Pexels