Ludolph now moves into the specific petitions of the Lord’s Prayer. The “address” causes him to reflect deeply on the mysteries of that introductory phrase. Whom are we addressing when we call on “Our Father in heaven”?

He focuses on three components in that opening petition:

1) Father, “whose children we are by faith.” This, Ludolph insists, is not the generic Fatherhood of God that everyone can claim by virtue of creation. Rather, this is the Fatherhood that is ours who are his children by adoption. It is the Fatherhood that kindles our Abba cries of longing. Interestingly, Ludolph also insists that “The title Father here should be understood to refer to the entire Trinity, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.” It is a prayer addressed to God our Father, rather than to God the Father.

2) Our, for “he has been given to us in love.” What a blessed revelation! We call God “ours,” not because we possess him, but because he has given himself to us. Because of Jesus, the Son of God, our Brother and Savior, we are invited into the Father-Child relationship that he enjoys, and “our” becomes one of the most majestic words in scripture.

The word “our” also empowers our love, for we do not pray to “my Father,” but to “Our Father.” Here Ludolph cites Chrysostom:

Here did not say my Father, but our Father, so we should pray for the needs of the whole body, and everywhere prayers are to be offered not only for ourselves, but for our neighbors. This destroys enmity, checks pride, drives away envy; it brings in charity, the mother of all good things, utterly abolishes all distinction of persons, showing that the king and pauper enjoy equality of honor. We are all united in the great and necessary things pertaining to eternal life. God has conferred on us all the same identical nobility, when he allowed everyone to address him as Father.

3) In heaven, which means “in your hidden majesty.” Ludolph, along with his two favorite commentators, Augustine and Chrysostom, teach us that “heaven” is the temple of God and the temple of God is in the saints. Thus, their major argument is that God’s presence—“everywhere and in every place … everywhere in his essence, his presence, and his power”—is intensely concentrated in “the saints and the just.” Ludolph is suggesting that the body of Christ—both those who live and those who have died—is the presence of God, heaven.

This raises a particular problem for Protestants. Ludolph is articulating a deeply Catholic and ancient confidence in the communion of saints that permeates our earthly reality. We Protestants usually believe that those who have died in the Lord have gone on to heavenly glory and have very little awareness of what goes on here on earth. Perhaps some may believe that they are part of that “great cloud of witnesses” (Heb 12.2), but if so, they are way up in the nosebleed part of the stands and most assuredly not accessible to us in any way. Ludolph, however, seems to see a seamless community of the living and the dead in Christ as we pray together to “Our Father in heaven.”

Note: For a brief introduction to Ludolph of Saxony, a medieval “best-selling author,” read this.

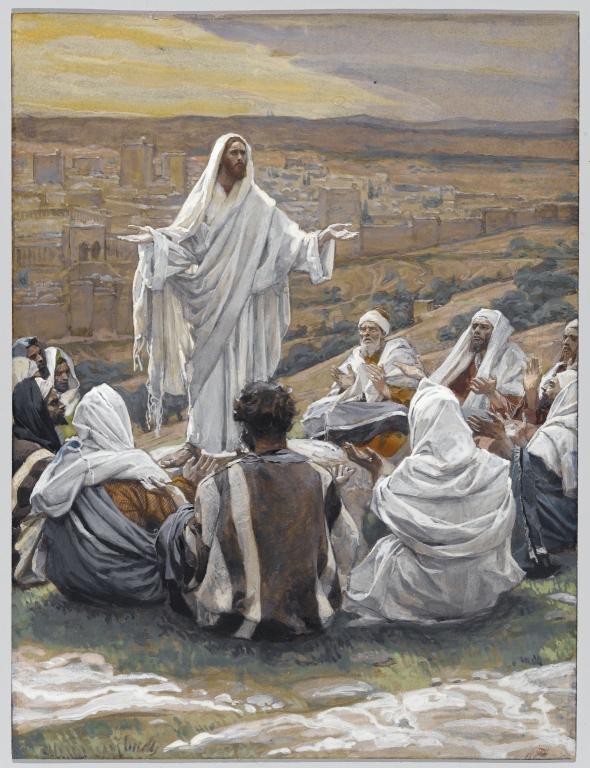

Image by James Tissot, c. 1886