![The Baptism of St Prince Vladimir [Volodymyr], sketch for fresco in Vladimir Cathedral, by Viktor Mikhailovich Vasnetsov, 1890 [PD-US], via http://www.picture.art-catalog.ru/picture.php?id_picture=3335](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/721/2016/08/Vasnetsov_Bapt_Vladimir-827x1024.jpg)

In fact, Archbishop Job says that if you take a walk through the Orthodox Church’s history of autocephaly and canonical territory, it’s mostly a story of Constantinople granting autocephaly to lots of churches, including Moscow. The way to understand it, the interviewer and Archbishop Job agree, is that there are several waves of autocephaly. In the first wave of autocephaly, the ancient Ecumenical Councils set down canons spelling out the autocephalous nature of ‘Rome (but the issue of Rome is a different question at the moment) – the Churches of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem and Cyprus’; indeed, these ‘are the Churches that had been approved at the Ecumenical Councils.’ Many of the Orthodox canons deal with these questions of autocephaly. Canon 34 of the Holy Apostles says that it ‘behoves the Bishops of every nation to know the one among them who is the premier or chief, and to recognize him as their head’; the next Canon (35) forbids ordinations outside a bishop’s own boundaries, especially ‘against the wishes of those having possession of those cities or territories.’ In the First Ecumenical Council at Nicaea in 325, Canon 6 speaks of the ‘ancient customs’ that ‘were in vogue in Egypt and Libya and Pentapolis, to allow the bishop of Alexandria to have authority over all these parts, since this is also the treatment usually accorded to the bishop of Rome. Likewise with reference to Antioch, and in other provinces, let the seniority be preserved to the Churches.’ In the second canon of the Second Ecumenical Council, autocephaly is even more pronounced:

Bishops must not leave their own diocese and go over to churches beyond its boundaries; but on the contrary, in accordance with the Canons, let the Bishop of Alexandria administer the affairs of Egypt only, let the Bishops of the East govern the Eastern only, the priorities granted to the church of the Antiochians in the Nicene being kept inviolate, and let the Bishops of the Asian diocese (or administrative domain) administer only the affairs of the Asian church, and let those of the Pontic diocese look after the affairs of the diocese of Pontus only, and let those of the Thracian diocese manage the affairs of the Thracian diocese only. Let Bishops not go beyond their own province to carry out an ordination or any other ecclesiastical services unless (officially) summoned hither. When the Canon prescribed in regard to dioceses (or administrative provinces) is duly kept, it is evident that the synod of each province will confine itself to the affairs of that particular province, in accordance with the regulations decreed in Nicaea. But the churches of God that are situated in territories belonging to barbarian nations must be administered in accordance with the customary practice of the Fathers.

The eighth canon of the Third Ecumenical Council at Ephesus in 431 speaks of the Bishop of Antioch performing illicit ordinations in Cyprus and calls on him to give that territory ‘back to its rightful possessor, in order that the Canons of the Fathers be not transgressed, nor the secular fastus be introduced, under the pretexts of divine services,’ that is, so that the governance of the church does not become a secular political power grab anointed by the sacraments, ‘lest imperceptibly and little by little we lose the freedom which our Lord Jesus Christ, the Liberator of all, men has given us as a free gift by His own blood.’ Again, this canon sets down the same principle:

It has therefore seemed best to the holy and Ecumenical Council that the rights of every province, formerly and from the beginning belonging to it, be preserved clear and inviolable, in accordance with the custom which prevailed of yore; each Metropolitan having permission to take copies of the proceedings for his own security. If, on the other hand, anyone introduce any form conflicting with the decrees which have now been sanctioned, it has seemed best to the entire holy and Ecumenical Council that it be invalid and of no effect.

The Fourth Ecumenical Council’s Canon 23 speaks of certain priests and monks who come to Constantinople without their bishop’s position and ‘stay there a long time, causing disturbances and meddling the ecclesiastical situation, and engender upheavals in the households of some persons,’ mostly because they refuse to stay in their own canonical territory. There are other canons, but you get the point: in this first wave of autocephalous churches, the canons of the Ecumenical Councils marked the canonical territory of the ancient churches of Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Cyprus.

Beginning with the autocephaly granted to Moscow in the sixteenth century, a second wave arose, mostly churches granted autocephaly by Constantinople:

The new wave of autocephaly always arose in response to political circumstances — the establishment of a new state or a new empire. Autocephaly was granted to the Church taking into account the situation of the state to solve an administrative problem. So this second wave of autocephaly continues nowadays — most of autocephalous Churches were proclaimed in the late nineteenth and in twentieth century.

But what this situation has engendered is a third wave: churches that are autocephalous from Constantinople that now want to have further autocephaly – ‘This is the problem both of the Serbian Church and the Russian Orthodox Church. But Constantinople it has already overcome it.’

The question, then, is: is Kyiv’s autocephaly a matter of the second or third wave? Archbishop Job’s answer? It’s the second wave: ‘Constantinople has always believed that the territory of Ukraine is the canonical territory of the Church of Constantinople’ – and this, despite the Moscow Patriarchate (in its first guise before it was dismantled by Peter the Great) absorbing the six eparchies of the Metropolis of Kyiv in 1685.

Is Archbishop Job making stuff up, then? No, because he makes his argument via Poland: ‘It should be kept in mind that it was on the basis of the Kyiv Metropolis that the Polish Church was granted autocephaly in 1924.’ How on earth does Archbishop Job come to that conclusion?

In 1924, Constantinople granted the Polish Orthodox Church autocephaly; this was shortly after Poland regained its sovereign state status in 1918. As Archbishop Job recalls, the Polish state appealed to Constantinople, saying, ‘We do not mind that Orthodox Christians live in Poland and practice their faith and have their own church. But we do not want the state to Poland to have a church that would be a column of an alien state, and even more – of an antagonistic state,’ which would have been the Soviet Union. When the interviewer objects that ‘the church problem can be a political problem, then,’ Archbishop Job clarifies: ‘For Poland it was no issue of Orthodox faith, Orthodox doctrine of Orthodox worship – this is religious issue and not of the state. But the Polish state faced a political challenge: it did not want the Orthodox Church in Poland to serve the interests of others states. And for this reason it appealed to Constantinople to be granted autocephaly and resolve political problems.’

But why could Constantinople grant the Polish Orthodox Church autocephaly?

On what grounds did Constantinople give Tomos in 1924 to the Polish Orthodox Church? Constantinople considered the Polish Church as former part of the Kyiv Metropolis. As we know, under Metropolitan Cyprian Tsamblak’s tenure the Kyiv Metropolis was located within the Polish-Lithuanian state, i.e. its borders extended to the territory of Poland and contemporary Lithuania. The same situation was at the times of Petro Mohyla, who was Metropolitan of Kyiv. The Kyiv Metropolis then was subject to Constantinople. As long as Poland once related to the Kyiv Metropolis that was in direct canonical subordination to Constantinople, Constantinople granted autocephaly to the Polish Church in 1924.

So, as long as Constantinople granted autocephaly to the Polish Church on the basis of the Kyiv Metropolis why today Constantinople alone has no right to grant autocephalous status to the Kyiv Metropolis? If it was possible in 1924 –it is possible today. (Emphasis mine.)

In other words, if it follows that the Polish Church was granted autocephaly on the grounds that Kyiv is in Constantinople’s canonical territory, then obviously Kyiv is Constantinople’s, not Moscow’s, canonical territory, which means that Constantinople alone has the canonical right to grant Kyiv autocephaly.

As a result, the case of Polish autocephaly is much more than the precedent case for Kyivan autocephaly, according to Archbishop Job, with all the similar circumstances of a state – this time, Ukraine’s parliament – asking for autocephaly so that its churches would not be serving a belligerent state (now Russia with the Russian World ideology). Much more radically – unless one wants to call foul on the Polish Church’s autocephalous status – it establishes that Kyiv still belongs to Constantinople, not Moscow:

The Ecumenical Patriarch has repeatedly stated that the Church of Constantinople is the Mother Church for the Ukrainian Church. He has repeatedly emphasized that he is the spiritual father for Ukrainians. So, the Ecumenical Patriarch continually monitors the situation of the Orthodox Church in Ukraine and is concerned over it.

Moreover, after the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine appealed to the Patriarchate of Constantinople to establish a canonical autocephalous Church, the request was considered at the last Synod and the Synod decided to bring this issue to the Commission for a serious and thorough study of the issue. So, Constantinople is considering this issue.

Speaking of this consideration by the Commission, Archbishop Job further emphasizes, ‘Constantinople does not need to study the Ukrainian issue in order to decide whether it has the right to grant autocephaly or not, whether the Ukrainian church is the daughter of the Church of Constantinople, or not, whether Ukraine is the canonical territory of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, or not. Constantinople knows it well enough, which it repeatedly emphasized and stated.’

Instead, the problems all relate to oikonomia. First, Archbishop Job commends the interviewer for succinctly stating that the Moscow Patriarchate ‘lives in its own parallel reality where no one else exists’ in the sense that it does not recognize Constantinople’s canonical right to Ukraine; the hierarch replies, ‘You have outlined the problem and in this outline you emphasized its complexity. There must be a certain process to solve this problem that we must explore and find. And this is precisely the objective of this Commission. If there was an answer how to solve the problem – it would have been solved long ago.’ He then goes further: ‘But it should be noted, and this is a canonical principle that one and the same territory can have only one Church. That is, two autocephalous Churches cannot simultaneously operate on the same territory. Proclaiming an autocephalous Church requires unity. Therefore, we should work on this unity.’ In other words, this situation where there is a UOC-MP that does not want autocephaly and a UOC-KP and UAOC that do want autocephaly is unworkable; this needs to be taken care of, as Kyivan autocephaly would essentially come to mean that the UOC-MP is Moscow trespassing on canonical Kyivan territory.

As Archbishop Job sees it, then, the problem lies with Moscow’s intransigence to canonical territorial reality. ‘Can’t we hold a dialogue?’ (emphasis mine) he says, and when pressed further about how the UOC-KP and UAOC are demonized by Moscow, he says – quite radically:

I will quote just one example from the Bible. Open the Book of Job in the Old Testament. The first chapter of the Book of Job tells about the dialogue (“dialogue” is the Greek for “conversation”) between God and the devil. In the Book of Job, God has a dialogue with Satan. If such a dialogue is possible — between God and the devil! — Why would the dialogue between Christians and especially between Orthodox Christians be impossible now?

This demonization, Archbishop Job says, is exacerbated by misinformation:

It should be noted that very different and contradictory information is being spread. This is not anything new: in any matter, i.e. political, if we compare the information submitted by American journalists, it can diverge with the information supplied by Russian journalists. And even in the same country, depending on political preferences of newspapers and journalists the information is highlighted differently in different newspapers.

I would say that the world is really poorly informed about what is going on in Ukraine. For example, I was asked a question by a bishop of the Patriarchate of Constantinople before my trip, whether Russian troops are still in Ukraine. He was under the impression that this issue was resolved after Minsk agreements. This is just one example.

The information is certainly available, and there are various contradictions in this information, but, frankly speaking, they write not much about Ukraine in the media outside Ukraine.

But ultimately, Archbishop Job clarifies, this is not a matter of states, even though it is (as with the Polish case) a state appealing for ecclesial autocephaly: ‘When referring to the Ukrainian issue, we are speaking about the Church globally. This is not only a study of one part or one branch, the question is considered in its entirety. Of course, this matter will be considered too.’ Furthermore, it is not a matter of private interest; when asked if he says all these things because of the rumors that he would be the Exarch of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Ukraine, Archbishop Job replies, with a laugh: ‘Never heard about that, first of all. Second, Constantinople could not be doing this either, because the study shall begin from the beginning, not from the end.’ Both of these pushback statements are believable because, as we’ve walked through the interview, the whole question of Kyivan autocephaly in relation to the ‘Russian world’ has been a matter of analyzing canons as oikonomia, not a matter of ideological state apparatuses or private promotion.

And here, then, at the end is finally why we in the UGCC care about this interview. It turns out that, quite recently, the UGCC has had its own spat with the Moscow Patriarchate (among the many spats of the past). On 25 July, UGCC Patriarch Sviatoslav complained to the press that the All-Ukraine Procession with the Cross for Peace, Love, and Prayer for Ukraine organized by the UOC-MP to celebrate the Baptism of Rus’, arguing that these celebrations arriving in Kyiv on 27 July were cynical because the Moscow Patriarchate was behaving like Russian aggressors using ‘human shields’ in Donbas by clothing their Russian World ideology with the cross. Shortly thereafter, the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew wrote to thank Patriarch Sviatoslav for supporting the Holy and Great Council. The Moscow Patriarchate’s Department for External Church Relations immediately issued a statement, condemning Sviatoslav’s statements as divisive, denouncing the unia (a bad word for Eastern Catholics) as ‘bleeding wound while the leaders of uniatism do not stop their blasphemous and politicized rhetoric aimed against the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church,’ and demanding the Orthodox (read: the Ecumenical Patriarchate) to resume ‘dialogue on the canonical and pastoral consequences of unia, forcibly interrupted through the fault of the Greek Catholics.’

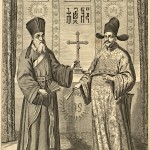

One’s reading of this scenario depends on one’s reading of the ‘Russian World’ vis-à-vis what the Orthodox canons actually say, as per Archbishop Job. I suppose we ‘Uniates’ really are a problem if indeed we are the ‘bleeding wound’ fomenting dissent with Moscow, which many who buy into this ideology presuppose is our mother church because we are both ‘Slavic’ churches and then somehow part of Moscow’s hazy cultural geography. But if the UGCC is really part of the Church of Kyiv, and the Kyivan Church is canonically part of the Ecumenical Patriarchate’s territory, then this whole situation flips. In this second geography, the UGCC is actually building a bridge with the UOC-KP and the UAOC while encouraging the UOC-MP to come into the fold; our ‘bleeding wound’ is actually a means of grace for the reunion of the churches that came into existence by the baptism of Prince Volodymyr on Constantinople’s canonical territory. This second reading, Archbishop Job is saying, is the only canonically valid one; the other one is a product of pure ideology. What’s more, Archbishop Job’s presence in Ukraine with those asking for autocephaly celebrating the baptism of Rus’ occurred at the same time as the celebrations held by the UOC-MP, but I don’t see him calling the UGCC ‘the unia.’ Maybe the question is for whom Eastern Catholics are a problem is more important than whether we are one in the first place.

The final question, then, is perhaps why anyone who is not part of the Kyivan Church would care.