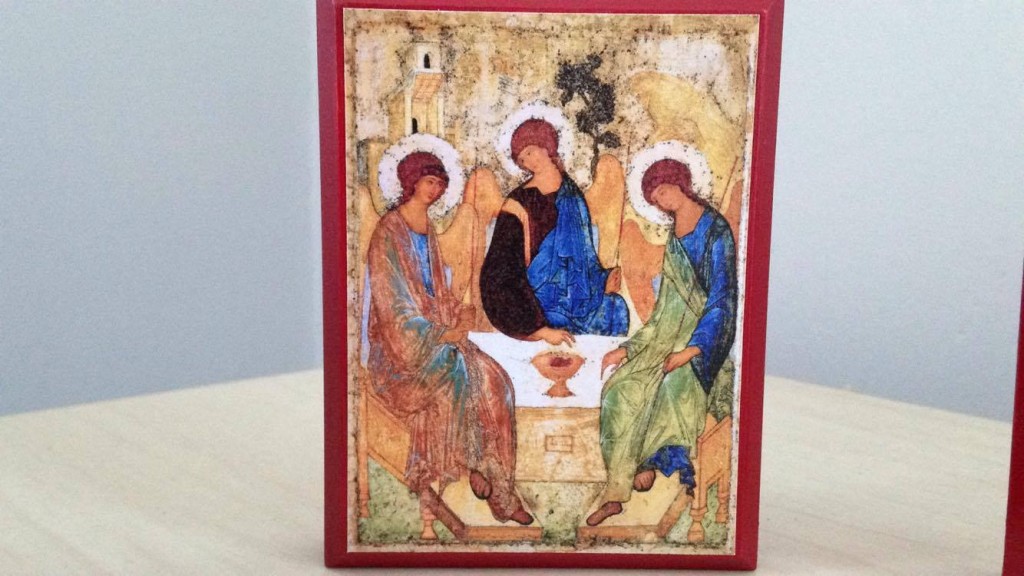

I’m blogging through my office decor this week, even though Byzantine icons are so much more than decorative for me. I’m going to start by looking at the fifteenth-century iconographer Andrei Rublev’s Icon of the Trinity.

There’s so much out there on this icon from the objective standpoint of what it’s supposed to be about that I feel like only a brief introduction is necessary before I get all subjective. The scene in this icon is technically the ‘Hospitality of Abraham,’ when the three angels visited the patriarch Abraham and told him he would have a son, only for one to reveal himself as G-d. In Rublev’s interpretation, the three angels are the Holy Trinity, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The cup of hospitality is also the cup that Christ drinks in his passion, which is also the cup that we share as the Body of Christ communing in his blood. In the background, there is a house for the people of G-d that come from the seed of Abraham, a tree that is both the Oak of Mamre under which Abraham worshipped and the wood on which our Lord Jesus Christ suffered and died, and a mountain of Transfiguration. It is an icon of the living G-d, the one being in three hypostases, as he invites us to share in his life.

This icon is also very convenient for me to have in my office because I teach in a very secular university in a very secular program. I do not feel threatened by the secularity of my university and program; in fact, I sometimes wonder whether it’s threatening that I am so open about my faith. To be sure, I never proselytize and would barely use the word ‘evangelism’ even in the most benign sense to describe what I’m doing; my openness about my personal faith is probably more due to the fact that I am critical of the act of privatizing theology because it goes hand in hand with the privatization of everything else.

I think this icon works for my non-threatening, non-private faith because it won’t be clear to my colleagues and students who generally don’t have a clue about Byzantine icons that it is in fact an icon. For all that is said about the haunting eyes of the icon looking at you, the three persons of the Trinity don’t look at the viewer, but at each other in relation to the cup. For those who are more secular than I am, it’s thus a nice religious portrait that isn’t so much religious as it is a mysterious work of art. In fact, I know evangelical Protestants who like to put this icon up on their PowerPoint slides when communion is served because they like it as meaningful artwork.

I do not think that icons are artwork; they are, as I said in yesterday’s post, the presence of G-d – or as St John of Damascus puts it, the images of the image of G-d. In Rublev’s Trinity, it is G-d drawing me in to share his life. In so doing, G-d works through the icon to remind me of what I’m doing here in the secular university.

One of the things that we are doing here at Northwestern is to build up our Asian American studies program. We had a new major in Asian American studies approved just last year, and we have to convince students that our little interdisciplinary program is worth their attention. It won’t be apparent for most people what this has to do with Rublev’s Trinity partly because the ideological alignment of Asian American studies, as I explained in my first class session today on Comparative Minority Conservatisms, has been historically with the radical Left. We are a product of the student activism of the 1960s, and we describe ourselves as an activist-academic discipline that seeks racial justice and the dismantling of systems of material oppression, especially in racialized communities of color. It’s a popular fiction that religion has not ever had anything to do with our discipline – historian David Yoo actually says in his introduction to Asian American religion that Asian Americanists have long regarded religion as what Marx called the ‘opiate of the masses’ – although it is much closer to historical reality to say that our theological alignment has often been with theologies of liberation.

This might sound quite far afield from Byzantine iconography, and it might be bizarre for some of my readers to discover that Eastern Catholic Person’s day job is being what those on the Right pejoratively call a Social Justice Warrior; for this, I do not apologize. I hope someone reminds me someday to write about how I learned that Byzantine liturgies can be sources for a renewed liberation theology, which is to say that I am aware of the supposed distance between Rublev’s Trinity and Asian American studies and consciously reject the notion that I have to compartmentalize.

After all, as I taught a bunch of Asian American evangelical pastors once, ‘Asian American studies is founded on the radical proposition that persons of Asian descent living in the Americas are in fact persons, not rugs. Beyond this statement, there is no agreement on what “Asian America” actually is.’ To be invited to the table of communion by the three persons of the Holy Trinity amplifies my awareness that I am not an ‘oriental,’ a passively asexual thing to be colonized, but a person. Certainly, this anti-racist understanding of personhood goes a long way in building up the house of G-d as displayed in the background of Rublev’s Trinity, which means that helping to build up a major in which students learn that Asian Americans are persons with agency in history is for me part of the transfiguring power of G-d’s mysterious grace in the world, undermining systems of oppression by the wood of the cross.

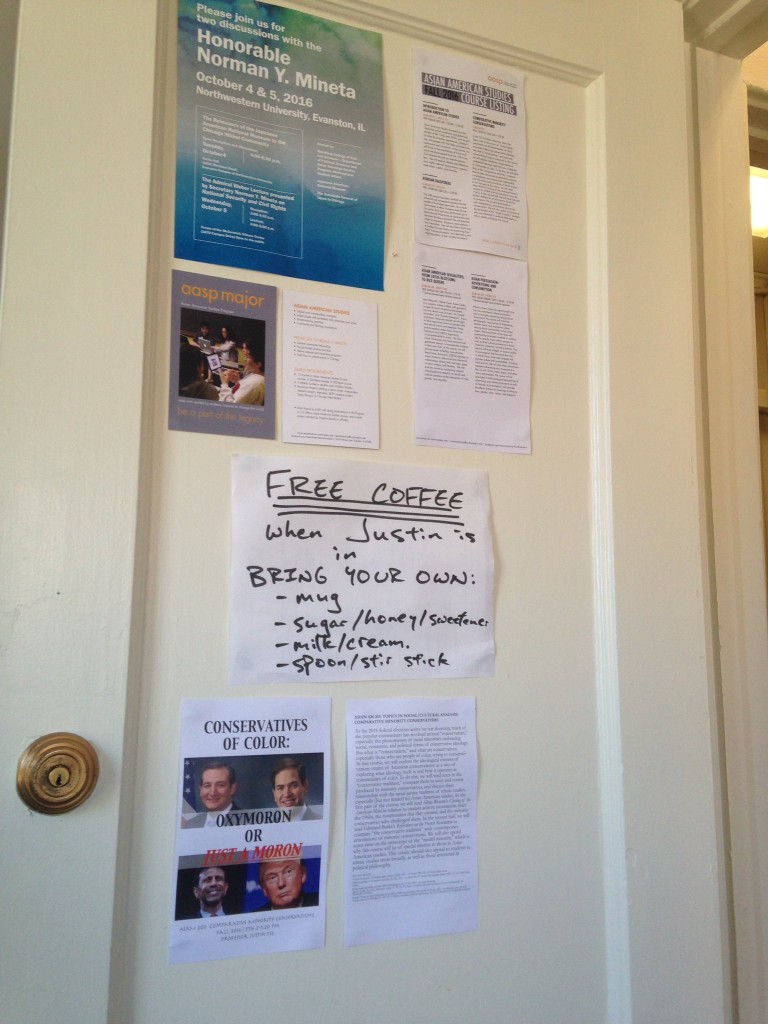

One concrete thing this icon has driven me to do is to put up a sign on my office door offering free coffee to anyone who wants to come visit. If some in my church wish to call me a Marxist heretic because of my commitments to Asian American studies (which is perfectly understandable, given the history of oppression that Eastern Catholics experienced under communist regimes – I’ll probably have to write a whole other post or series on that!), this is perhaps where my radical friends may detect some ideological heterodoxy in relation to them as well. Those committed to overturning oppressive systems are often accused of paying more attention to structure than agency; indeed, the condemnations from Bishops of Rome from Pius XI to Benedict XVI against communism stress that where Marx and his diverse array of followers go wrong is that they see the individual as a cog in a greater ideological machine chugging on to smash bourgeois capitalism. In what Marx called a ‘ruthless critique of everything existing,’ offering coffee as an act of hospitality is precisely this kind of individual act that doesn’t make a structural difference, if not mystifying the structures even more with the ideological form of kindness.

Or does it?

This is where Rublev’s Trinity speaks to me. To be drawn into the life of G-d and to build a program stressing our personhood does require lots of planning and structure and thinking about big systems and the critical analysis of race and capital, but all of that is nurtured by small acts. You can’t build a program (especially one geared toward social justice) unless the people in the same building like each other, are collegial with each other, have good conversations with each other as persons. The facilitator of that is often food and drink – or in my case, since I brought a coffeemaker from home, free coffee.

I’m sure someone will ask whether the coffee is fair trade or not (I’m not sure) or whether it’s actually the program’s responsibility to provide the coffee (they’re generous with sugar, and I’m told there’s milk and cream downstairs in the kitchen, although I take my coffee black), but this is not the point. Rublev’s Trinity invites me to be at table, but the hospitality of Abraham also set that table. The makrodiakonia (the big-picture service of social justice) of what Paulo Freire calls the ‘pedagogy of the oppressed‘ is indeed important, but it bears remembering that what Freire meant by overturning oppression was to liberate both oppressors and the oppressed to see themselves as human persons who can speak the word about the world and become actors in history. Such personal liberation means that makrodiakonia comes hand in hand with the small acts of mikrodiakonia, the tiny gestures of hospitality that keep my heart open to the other.

Rublev’s Trinity is in my office to keep me focused on building a house of justice through the small acts of hospitality, to remind me through the week in the world that I share in communion in the life of the Triune G-d, to show me that what purity of heart I seek is not to be found in trying to be pure ideologically but in simply being a person overflowing with love that can only come from the Holy Spirit.