Our Chinese church, like most other Chinese and Korean churches, had both Chinese and English services, which is code for worship in the style of adults and children. In fact, our particular church had separate Mandarin and Cantonese congregations, so you can imagine the politics. What my mom meant by playing the piano in church, then, was to be able to play for the Cantonese service. Sure enough, there were pianists for the English service, which had triumphed in the worship wars and was led by a chain-smoking guitar player who always looked stoned while leading the band in ‘times of refreshing,’ as the Vineyard Music lyrics had it. I think my parents didn’t like that guy, and they didn’t like the girl on the keyboard either because her tops were always so low-cut. Actually, she was pretty hot, which probably didn’t help her case. As a result, I ended up playing for the Cantonese service.

It was then that my mom taught me the secrets of the hymnbook. She said that in classical music, you literally try to play every note that’s written out for you on the page. But in worship playing, you just need to know what the chord structure is. All that stuff that I had learned in music theory therefore now applied. The idea was to simply figure out what the chords were from the music, and then you can invent a left hand while playing the melody on the right. I asked her what that would mean practically for the left-hand accompaniment. Something like Alberti bass, she said, as long as the chords were consistent. Some of the fancy hymns weren’t like that, though. The Doxology, better known as the Old One Hundredth in Presbyterian circles (‘Praise God from whom all blessings flow’), changed chords for every note. Oh, and by the way, she added, we do that Doxology for every service.

And so it was that I began chording. The problem was that I was also an early teen, and if most twelve-year-olds don’t want to talk like their mothers, you can sure as hell bet that I did not want to play like my mom either. For the first few services, I did as I was told, and my mom liked it, which meant that I was deeply unsatisfied. I needed to sound like something else.

Something else meant that I wanted to sound like what I’d heard in school. I grew up going to a school that was housed in the First Assemblies of God church in Fremont, California. We were, in a word, Pentecostal; our Bible lesson workbooks even had language about being ‘controlled’ by the Holy Spirit, which offended some of the teachers who were of a more Southern Baptist background. There, I had grown up hearing the piano played to accompany choruses and hymns, and it did not sound like the Alberti bass of my Chinese church. It had oomph. It had chords I did not know how to produce. It had the ability to get you out of your seat and your hands in the air.

The closest cognates that I could find were twofold. First, my parents had gotten into the Gaither Homecoming series, in which the pioneers of the Gospel music industry Bill and Gloria Gaither assemble their gospel music friends into a choir. The piano playing was both folksy and fancy, mostly thanks to a guy called Anthony Burger whose fingers would just fly over the keys. But second, my father had been ordained in the black church in Oakland, and I remember that when the Rev. J. Alfred Smith, Sr., got excited and broke out into song, there was a pianist who accompanied him. She could match his pitch by ear. She knew what chords to play, and they were some funky chords, not at all the tame major triads I knew from the Chinese church hymnal. I needed to find out what these chords were.

So I called up the Pentecostal music teacher at the Assemblies of God school, and we agreed to meet for ‘lessons,’ if they could be called that. We agreed that these were unusual piano lessons because we weren’t trying to learn music, and we didn’t have to go over basic music theory. It was really about style. I bought myself a do-it-yourself chording book for Gospel music, and the teacher had a look at it and thought it was good, but it also didn’t get me where I wanted to be, which was out of Alberti bass.

Instead, she said that perhaps an important thing to do would be to listen to some music. Then she handed me a cd with an angel’s wings spread over the words Simply Worship. The mysterious artists on the disc were simply called ‘Hillsong Music Australia.’

I did not know why we were listening to Australian music, but I recognized two of the songs from church: ‘I Give You My Heart’ and ‘Shout to the Lord.’ But obediently, I popped the disc into the cd player, and immediately I understood why the teacher had given this album to me. It sounded exactly like how she plays the piano, and what’s more, I knew this song ‘I Will Run to You‘ as the ‘not by might, not by power, but by the Spirit of God’ song. The style of the piano is heavy. The point is to sustain the worship, like what we in classical music call a pedal point. It is supposed to feel like your two feet are being anchored into the ground while you are ascending into heaven.

Hillsong has a unique sound, and part of it, the teacher informed me in the next lesson, is a mysterious chord often marked as ‘4sus.’ The trick is that whatever key you are in, if you take the fourth and then instead of using a triad of 1-3-5 (which is how chords are normally played, at least in the Chinese church), you use 1-4-5. This is the plagal suspended chord; play it, and you will suspend everybody’s hands in the air. Later on, another friend told me that if I wanted to switch things up a bit and add some spice, I could also play all my chords 1-2-5. I’ve tried that, and that takes me in the opposite direction: that’s the mute button. Also, I learned that if you want to do one of those key changes that gets you higher and higher into the sky, you find the fifth of whatever key you want to go into, hit a minor seventh, and voilà, you are in the new key.

All that’s to say that by listening to Hillsong, I learned to play the piano like a trashy Pentecostal. This is the Hillsong before they became ‘United’ and hipsterfied. My piano playing is not respectable; it is openly manipulative, willfully heavy, and trashy as sin. It’s the kind that reminds you of the Tammy Faye hairdo and makeup; it’s the open eroticism that leaves no doubt in any outsider’s mind why it is that the televangelists had so many sex scandals. It’s no surprise that when I wanted to up my chording skills more, I pulled the ex-gay worship leader Dennis Jernigan aside at a conference at Focus on the Family, and he gently instructed me to listen to Keith Green – not just for the words, but for how he uses the piano to sustain and drive the music. When I heard Keith Green, it also sounded familiar. It’s how I play the piano.

And that brings me to my cantoring. I’ve made the joke that in Richmond, we sound like a bunch of Pentecostals trying to chant Galician tones. I’m sure my heavy cantoring, which is a holdover from my Pentecostal piano playing, contributes to that mess. But I also wonder whether in just simply becoming increasingly less conscious of it by losing myself in the services of the Kyivan Church, I am coming into a deeper understanding of what ‘not by might, not by power, but by the Spirit of God’ means. It’s a favorite line from Pentecostals; indeed, when I took correspondence courses from Calvary Chapel Bible College, the senior pastor Chuck Smith always cited it because it was inexplicable otherwise how tens of thousands of pot-smoking hippies came to Christ and started a Jesus Movement that has impacted contemporary evangelical worship to this day with its informal sensibilities, repetitive choruses, and – yes – trashy piano playing.

But where is it from? Does it really describe revival, erotic worship highs, and trashy manipulative music? Not by might, not by power, but by my Spirit, says the LORD of hosts are the words of the Prophet Zechariah to Zerubbabel about the rebuilding of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem after the exile to Babylon. In these days when Pentecostals and their dispensationalist evangelical allies are in trouble because of the ideology mostly from them that got Donald Trump to move the American embassy to Jerusalem, it is worth remembering that the Holy Apostle Paul describes in the first letter to Corinthians both the physical body and the gathering of the people of God as the temple of the Holy Spirit. It is this temple, this house, this economia that is built not by might, not by power, but by the Spirit of God – which means that any Christian who can quote this prophetic text and still support this move to force the apocalypse into manifestation has to grapple with the internal contradiction of their own thinking. As the Pentecostals joyfully misquote the twenty-second psalm, the Lord is enthroned on the praises of his people. Where the Lord’s spirit is, there is the temple, where the house of God is built. The fulfillment of biblical prophecy is not in some apocalyptic disaster signaling the Day of the Lord: that is building the temple with might and power. It is rather that the Spirit of the Lord has been poured out on all flesh, and trashy though I may be, our gathering is the mystical representation of the cherubim where we sing the thrice-holy hymn to the life-giving Trinity and lay all earthly cares aside.

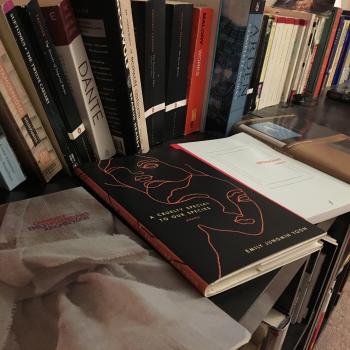

I was nominated by our blog’s former resident Latin Catholic Person, Eugenia Geisel, to do the Facebook Album Art Challenge. Posting the covers gave me some nostalgia that I wish to work through. I am therefore blogging about it too now concurrently. Perhaps Eugenia will do so as well on her blog, Lipstick on My Relics. This is the fifth of ten in the series.