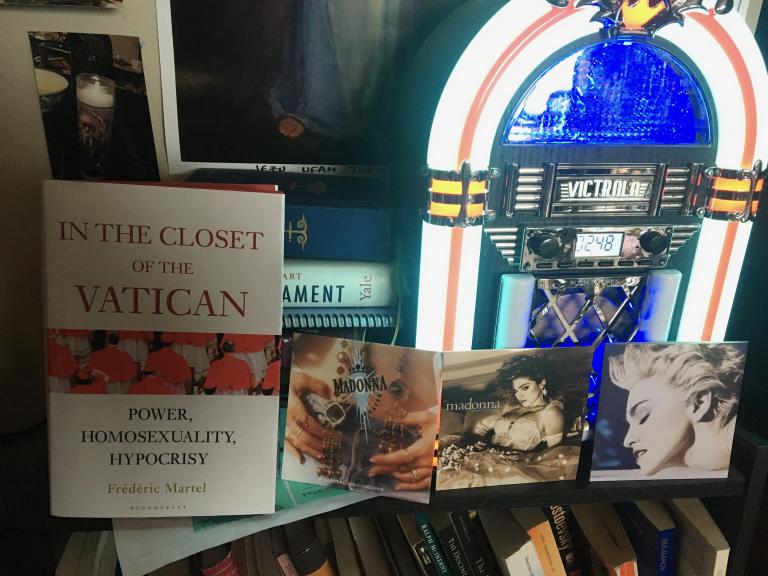

For those who are among the cheeky in the Latin Church, Ash Wednesday is what they call a ‘Catholic coming out’ day, as the ashes on the foreheads of those who walk our streets, work in our campuses, and go about their everyday lives mark those who have attended mass that day, unless they are very traditional and have the ashes poured on top of their heads. I hear that term less this year, perhaps because I am Eastern Catholic, and not only are we on a different calendar that is a week apart this year, but our Great Fast begins with Forgiveness Vespers on the evening of Cheesefare Sunday. I can’t help but think, however, that the notion of ‘coming out’ this year is a bit inconvenient for our Latin sisters and brothers, given the hubbub of the publication of Frédéric Martel’s In the Closet of the Vatican: Power, Homosexuality, Hypocrisy. It would be one thing to say that the book, despite its copious research, is fundamentally riddled with gossip and innuendo. It is quite another to admit that it is embarrassing all the same, partly because it details much of what we already knew.

To be making my way through Martel’s salacious book on Cheesefare Week, of course, is to form an interesting pairing with the letter of the Holy Apostle Jude at the weekday liturgies. In that epistle, St Jude is not invested in lost things; if anything, he’s concerned about the church’s sexual teaching. The message of grace in the Gospel, it seems, has been perverted by some who say that ‘wantonness’ is compatible with Christian living; with example after apocryphal and pseudigraphical example, Jude warns against such fantasies, reminding the faithful of the Lord’s judgment. Of course, there is more that we read about this week too; we also hear the third letter of the Holy Apostle John the Theologian to his friend Gaius, whose church is being divided by some who want to take pre-eminence in political order, as well as the Passion Gospel according to the Holy Evangelist Luke the Iconographer. But even in these texts, the focus is ultimately on bodies in relation to the Body of Christ, the way that the church should be ordered with the practices of humility and peace and how they fall short in practice of apostolic teaching.

As they all say, I was not planning on buying the book at all, which is to say that my interest was seriously piqued when I read Andrew Sullivan’s triumphal take on it, and then Rod Dreher raining on everyone’s parade. What tipped me over into ordered it was reading James Alison on it, not least because I thought, as I learned that Alison had been one of Martel’s sources, it was going to be wittily good. Those who apparently comb through my blog for evidence that I am somehow delinquent in my acquiescence to the teaching of the church will think they have me by the proverbial balls this time. It turns out that the first pieces on the Catholic blogosphere that I ever read were the Vox Nova interviews with Alison on him being an uncloseted gay man who is also a Catholic theologian claiming not only orthodoxy but also affinity with Benedict XVI, which led me to his talk, ‘Is it ethical to be Catholic?‘ and then my reading of his work, which, properly speaking, is on the thought of René Girard. I found it engaging then, and I have been re-reading Faith Beyond Resentment: Fragments Catholic and Gay with interest this week, mostly because I’ve missed it and also because I feel like I never really understood it when I first encountered it in 2012, eleven years after it had first been published.

Alison’s thoughts on being gay and Catholic do not seem to have changed very much, if at all, from 2001 to 2019; he probably held the same views before then too. What he points out in both his review of Martel’s book and in his 2001 book, as well as in the 2006 talk, is that a Girardian reading of the Latin Church would start from the observation that the teachings on the ‘intrinsic disorder’ of homosexual desire, which as he points out clashes with the Tridentine understanding that all desires are ordered toward the good, make for a closet, especially among the ecclesiastical hierarchy. For Alison, the power of Martel’s book is not in its exposure of the hypocrisy of those who run the church — and most certainly not in some awful association between gay priests and sexual abuse — but in its laying out of the fact that there is a closet that is formed by those who have to hide their desires because they are told that they cannot be holy otherwise. In Girardian terms, the queer is the scapegoat for the ongoing continuation of the hierarchical church and its teaching, and the worst part is that the scapegoating is self-inflicted, as closeting is a form of self-exclusion. That, Alison argues through biblical exposition and theological reflection, is the real sin, because it is the association of the people of God with acts of violent exclusion.

If I have any critique of Alison, it is of his optimism, both then and now. Somehow, he believes that the exposure of the revelation of the closet will be a catalyst for change. On the same Girardian terms, I am a bit more pessimistic; in I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, Girard points out that the victim has been elevated to that which constitutes the community. Alison is gracious throughout his work, of course; he constantly refuses the position of queer as victim, arguing that it will pervert the possibility of transforming a world in which a closet will no longer be necessary. The trouble, though, is that as I was musing over the 2001 book, I could not help but feeling that the thoughts were deeply 2001, in a time when the ugliness of neoconservatism was really beginning to show its face in the beginnings of the post-9/11 era but at a moment when it could not be known that even after the 2008 financial meltdown, there would be a radical commitment to the status quo, to making sure that the exposure of scandal simply results in institutions, in the immortal formulation of Slavoj Žižek, knowing what they are doing and doing it anyway. Indeed, for Žižek, that modus operandi is what is the true perversion, as the pervert, in Žižek’s revitalization of psychoanalysis for political theory, is the one who knowingly acts out the fantasy while knowing full well that it is bankrupt.

Still, there is something beautiful about Alison’s musings on the closet. As I meditate on Jude in the context of the Cheesefare Week readings, there is a sense in which the heresy that St Jude decries, which is about ‘wantonness,’ has very little to do with the order of desire that Alison wants to unrepress. In fact, what Alison seems to be suggesting that the very existence of a closet is a moral failure, because in the terms of the Latin catechism, chastity is not the repression of desire, but its integration into the embodied beingness of the human person. If a church produces a closet, especially in the attempt to keep the ‘pre-eminence’ of some (as 3 John has it about Diotrephes), then its moral practice is called into question, and those of us who are in communion with her, as the Holy Theologian John is with his brother Gaius in his sister church, have reason to be concerned and to pray for her well-being.

Today for our sister church is Ash Wednesday. The prevalence of the closet in her midst is symptomatic of the closeting of much in the world. Indeed, as queer theorists like Michael Warner, Jasbir Puar, and Yasmin Nair have demonstrated, the advent of what Puar calls ‘homonationalism’ and other queer normativities is often used to showcase a kind of progress that masks much more serious violent acts, especially the rendering of subjects deemed ‘terrorists’ to be killable. It is strange that a world where to be queer is normal is one where the closet remains prevalent and there are so many skeletons in them. Here, our moral reflections might begin anew, especially as the Great Fast is upon us, and we enter into a time where we again are confronted with ourselves and learn again to be human in a closeted world. I don’t know if this sheds any new light on the term ‘Catholic coming out’ day, though. That, because it is a reference to the practice of ashes that we don’t have in our churches, will be for our sister church to discern in her own process of conscientization.