I was eleven when my grandpa died. He was not doing well when he did. A few months before he passed, he had stopped taking his anti-psychotic medications. He was clinically depressed, and had been for quite a while before the vogue began, and was about to get into a lot of trouble for taking a pair of scissors to a neighbour’s flowers just because he liked them and wanted to take them home. As it turns out, he was in even more trouble with his colon. Having thrown up fecal material, he was rushed to the hospital, where he remained in intensive care for months, one day an improvement, another sliding down into the abyss.

The night he died was like any other, in the sense that he had many nights when he was going to die and he didn’t. He was even revived twice. My sister and I were rushed to a babysitter, where I spent the night alternating between working on a ‘country report’ assigned at school (I had picked China, only to realize that the history section was going to be murder) and strategy charts for Warcraft II in a time when my sixth grade teacher had not yet caught on that I was doing witchcraft. We got a call later that night that grandpa really had died. He was not mostly dead. He was all dead. There was no reviving him this time.

My father told me about how it went down a few days later. Grandpa’s heart monitor had suddenly flat-lined as the family had gathered, and there was no getting a pulse back. Knowing it was the end, my father went into pastor mode; he was, at the time, the unpaid pastor of the Cantonese congregation at our Taiwanese church in the San Francisco Bay Area, and it became clear that the pastor of our relatives in the City, as San Francisco is called for us suburbanites, was not going to make it on time. Dad said that he got out his Bible, held up his hand in blessing to my dying grandpa, and declared in Cantonese, I am the resurrection and the life. He who believes in me, though he should die, yet shall he live. For the first time in this whole ordeal, Grandma, who had fought with her husband for years over his stupid decisions and incomprehensible Cantonese as the privileged son of a Shanghainese tycoon who had lost everything to the communists and made sure you knew it as the excuse for his delusional activities, cried. As she through sobs said good-bye and even told him that she loved him, he died.

To me, this scene is a deeply theological moment, one that I feel caps off this Great Fast well. On and off this Fast, I have been thinking about death, mostly because what started it off for our mission in Chicago is that our dear friend, Fr Myron Panchuk, died. At the end of this Lazarus Saturday, I come back to it, finding in its messiness a renewed sense of what it means that the Lord is the resurrection and the life though unlike Lazarus, my grandfather was not called out the tomb in his grave clothes after being four days dead. Perhaps it is from the mothers and fathers’ extended meditation on Lazarus that began last week in the Matins for the Sunday of St Mary of Egypt that started my reflection. In the canon, the tropars are all about Lazarus, the poor beggar sitting outside the rich man’s gates waiting to eat the crumbs at his table. It’s a favourite of my father’s too, who studied the passage in depth with his seminary professor Joel B. Green in a course on wealth and poverty in the Gospel of Luke. Dad always likes to point out whenever he preaches this passage that the rich man was so filthily wealthy that he’d use the bread at his table as a napkin to wipe his hands, then throw it out of the door where Lazarus waited to catch it.

In the Matins canon last week, the tropars for Lazarus and the rich man suddenly merge with Lazarus of Bethany, and the stichera at Vespers for all the subsequent days, including the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts on Wednesday evening, do the same. In the mind of the church, the family at Bethany seems to be a financial mess, Lazarus as poor, while Mary his sister is a twofold annoyance, once to her sister Martha in Luke for sitting at the Teacher’s feet instead of helping her with the housework, and another to the disciples for breaking an alabaster jar over Jesus’ feet. There is indeed something to be said here about Mary of Bethany’s obsession with the feet of the Lord, but more pertinent here is that Lazarus is probably not wealthy and certainly not powerful. It is telling that he is mourned by so many Judeans in the passage, except that after he is raised from the dead, they make plans to kill him again.

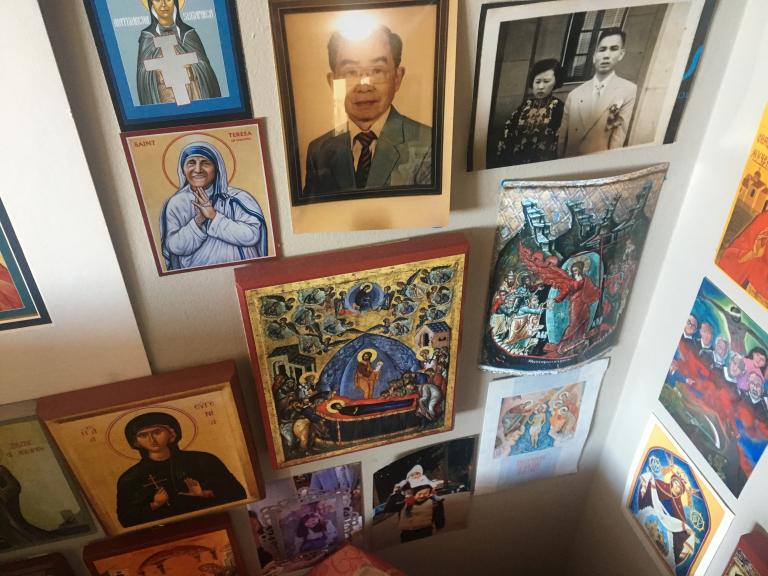

In this way, I often identify my grandfather with Lazarus. I wouldn’t say he was poor, dispossessed though he was by the communists, because he did have a job at a large financial institution in Hong Kong. Of course, the real reason the family managed to be middle class was that my grandmother was the breadwinner: she was the headmistress at a prominent Methodist school. My grandpa, on the other hand, was employed by a relative who ran the local branch of the firm he was at, and was taught to look busy at his desk by smoking. The only result of that advice was that he became a chain smoker — he was unproductive otherwise, which is why he was never promoted — and the smoking destroyed his health, first his skin, then his digestive system. It’s why Grandma, like the two sisters of Bethany, often fought with him. The two of them, both refugees in Hong Kong after the communist revolution up north, had been put together by a matchmaker, who had been unaware that they had both been dating other people in Shanghai and Guangzhou, respectively. They didn’t even speak the same Chinese language: he spoke Shanghainese, she Cantonese, and for the first few years of their marriage, they communicated by sign language. She became wildly successful in her career, while nothing ever worked out for him. The only people who liked him were children, to whom he told long, meandering stories. I know: he told me as many stories from the classic Journey to the West he could before he died.

The raising of Lazarus reminds me that even this man, my grandpa whose every aspect of life from dispossession to employment to health marks him as a loser, will be raised from the dead. This is what it means that my father raised his hand at him and pronounced the resurrection and the life over him. It is that he, along with Lazarus as well as every person whose life is marked by alienation and oppression, will hear the voice of the Lord on the last day to come out from the tombs. It means that even I will hear this voice, I who must admit that if there have been struggles in my own career — I spent five years on the academic job market cursing every father figure who had assured me from the outset that it was a stable profession until I finally landed a permanent position — they have nothing to do with feminism or affirmative action or any of the other things that folks blame for male alienation and underemployment. I come from a family of at least four generations on both sides of strong career women and feeble men who make terrible vocational decisions. And yet, all of us will still rise on the day of resurrection.

I carry this reflection, one that has stewed since the start of the Fast, into Great and Holy Week. More than any other year, this year’s Fast has been almost atheistic, with my thoughts concentrating on who we are as common inhabitants of this earth without masters to free us. If there is anything that is cosmically supernatural, it is in the stuff of ordinary life; if a theology of the body can be spoken of, it will be in the language of our bodies instead of the words of a Holy Father whose feet of clay were most devastatingly revealed in the sex abuse crisis. If the Fast is a time for me to relive my catechumenate, the teaching that I have received this year concerns the absence of God precisely because he is present in our midst. With Lazarus, my grandfather, and the rest of alienated humanity, I journey now into the city for Palm Sunday, anticipating the events of this week that will show the Lord suffering among us so that we will all rise with him.