Fr Myron Panchuk used to draw a lot of significance out of the fact that he was born on the same day that the meltdown at Chornobyl happened. I was born in the same year. Today’s Great and Holy Friday coincides with the anniversary.

The impetus from Fr Myron’s dissertation on the dreams of professionals in Kyiv and the images of the shattered dreams for Ukrainian peoplehood came from a dream he had. He dreamed that he was eating a soup with broken eggshells in it, and as he realizes that they are pysanky, the colored eggs for Pascha in our tradition, he says out loud, I cannot eat this soup. He quickly understood as he woke up that he was dreaming of Chornobyl, that the trauma of 1986 had not left him, or the Ukrainian people, or the world, as he contemplated the devastation of the meltdown of the nuclear reactor and the hubris of the Soviets in playing down the ecological damage of the radiation that fell out from it. From this dream, Fr Myron also understood that there was continuity in the ongoing trauma of colonization in the Ukrainian psyche, that there was a thread that tied the Holodomor artificial famine of the early 1930s to Chornobyl in 1986, and from there to the protests of the Maidan in 2014, which broke out immediately after he collected the dreams of professionals longing for real political freedom in post-2010 Ukraine.

I am not Ukrainian, and that the fall-out at Chornobyl affects me suggests that nationalism is too narrow a frame with which to view the meltdown there. Serhii Plokhy’s masterful account of the events, as well as Julian Hayda’s documentary about it, positions it as the ecological disaster that it actually was. Radiation knows no borders (as Fukushima has also reminded us), and neither did the Soviet Union, for that matter. The accounts bespeak very little of a Slavic culture, or Ukrainianness, as the culprit for the disaster. What is at fault is the hubris of blind faith in a scientific, technocratic apparatus, combined with the political-speak that played down the devastation when it happened and left thousands exposed to the direct brunt of the radioactive waves.

Fr Myron may have been born on the day of the disaster, such that it even haunted his dreams, but I, as well as Julian Hayda, are of the generation that came after Chornobyl. We are the ones, we are always told, who are going to be able to overcome the ecological crisis that we are in; that Greta Thunberg and those she has inspired still have to shout so loudly about how adults have sold their future from them indicates that that new, post-Chornobyl culture has not yet been created. One of the last things that Fr Myron said to me before he died was that it is in the absence of the father that the children will grow up. With Thunberg and the children of the climate crisis, we now realize that those of the generation before, the one that gave us Chornobyl once and Fukushima yet again, are not going to help us. We are, as Slavoj Žižek often says, all alone.

Great and Holy Friday opens with the Passion Gospels service, the special journey in Matins when we move through the accounts of the Lord’s Passion. I told our cantor in Richmond, who cantored the service for the first time last Thursday night on the New Calendar, that by the end of it, God is definitely dead. There’s no waiting, as in the Good Friday services of the west, for the ninth hour. It is finished, and it had better be, because the readings for which we must stand are absurdly long.

But the Passion Gospels service opens not with the accounts of the crucifixion, but with what are conventionally called the Farewell Discourses in the Gospel according to John. A clue has been given about the significance of this placement in the suggestions for the ninth hour readings for Great and Holy Wednesday: the schedule tells us to read all four Gospels, but John only up to the thirteenth chapter, the thirty-second verse. It is a foreshadowing that the whole of the Farewell Discourses will be read on this day, the conversations in which the Lord lays out the basis of a new society — indeed, a new sociality — that is founded on loving one another, as one might die for their friends. The cultural practices that will be created beginning with the community gathered at table with the Lord will be marked by mutual service and a deep communion in which they will be one, as the Father and the Son are one. It is with these words that the Lord enters into his Passion.

The Passion narratives illustrate the contrast of power to the new people that the Lord is creating. In them is found all kinds of collusions of power, colonized elites siding with colonial agents of empire, to culminates in Jesus hanging on a cross. Abandoned into the hands of sinners, the Lord cries out from the cross that he has been forsaken. Some smart aleck tweeted at me when I wrote on the Christian atheism in the Peterson-Žižek debate that Christ does not become an atheist on the cross, that he is quoting the opening words of Psalm 22 (23 in the Septuagint). I am sorry, but no one has time to be intertextual when they are being crucified; if anything, these are the words that arise from his unconscious to fit the present situation of divine abandonment. Such commentators, so afraid of the word atheist, are usually the ones who miss the point of death-of-God theology and its Nietzschean roots. The point of Nietzsche’s madman in The Gay Science who cries out that God is dead and we have killed him is to scream in despair that the machines of the modern age have so thoroughly colonized everyday life that we too have not only been handed over to the machinations of sinners, but to the tentacles of the machines themselves. Death-of-god theology is a recognition, not a celebration, of the colonizing power of the secular, which turns out not to be a discursive ideology, but a material and institutional reality.

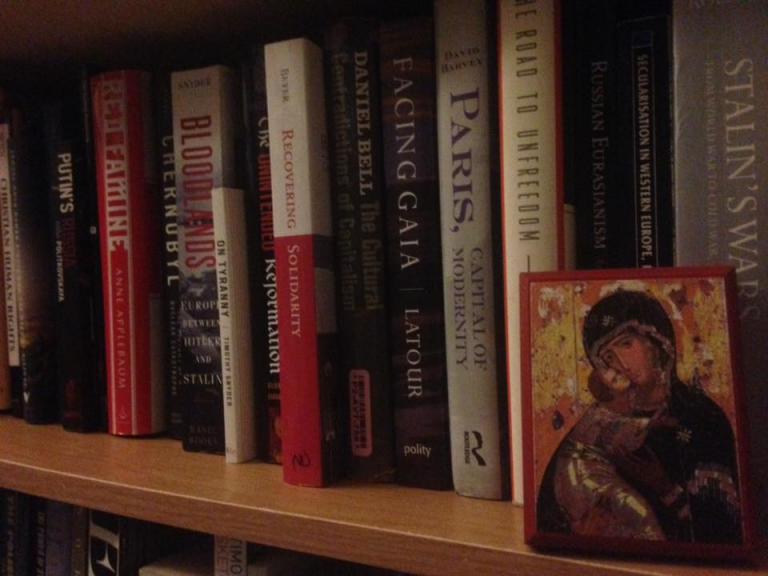

Is not the Passion the appropriate frame for the remembrance of Chornobyl, then? Handed over to a world that is said to be posthuman, the ecological crisis rolls onward. But the point of the Passion Gospels is not only this horrifying analysis of sin as a process of power; they also lead with the possibility that there is a new society that arises from the cracks of this totalizing institutional world. That I am born in the year of Chornobyl means that in the repetition of the Passion in our time, the community that the Lord formed — the one that we might dare to equate with the church with apostolic succession to the moment that Jesus celebrated the Passover with his disciples — continues in Christ’s Pascha. To journey into the Passion is to enter into this Passover. To recognize it in the ecological crisis that was laid bare by Chornobyl is to reflect that climate change is not only about science, but also about a consciousness that is formed by the radical practices of love in the midst of a world of scientific hubris.