A few months ago, I got a message from someone who has been reading my blog and my academic work. She said that she had been very taken with the concept of jook sing, the ‘hollow bamboo’ that describes Chinese Americans born in North America who might look Chinese but have no sense of Chinese culture. Over the summer, I had worked through a series of posts on being Cantonese despite being a jook sing, as I rediscovered who I was through the prodemocracy Umbrella Movement protests in Hong Kong and my conversion to Eastern Catholicism.

She had sent my posts about it over the summer to her friend Julian Saporiti, a PhD student at Brown University. Julian is a musician. He read it and then wrote a song.

The song is titled ‘Jook Sing Cafe.’ I have Julian’s permission to post it.

In the song, Julian works through the confusion of a jook sing experience. He talks about how Cantonese and Taishanese are spoken too quickly to the point of him losing the sense of the languages. He juxtaposes burgers and the Calgary Stampede in which a jook sing might participate with dragon boat races that are mostly ‘white folks anyway.’ He comments on Hong Kong not being able to ‘make up its mind’ between ‘Ma’s Chinese dream and Pa’s British fantasy.’ He even alludes to the Umbrella Movement with the ‘yellow umbrella,’ though he does not ‘comprehend half the sounds.’ Jook sing indeed.

These are Julian’s reflections on my experience. Mine are quite a bit different. While I love a good burger, I don’t know much about the Stampede, except that my mom and dad used to live in Calgary and went once, I think.

I started calling myself a jook sing after I was denied the joy of being one in Hong Kong during my 2012 field work. I was on a radio show with some radical democratic Protestant Christians, and as I spoke, the online commentary was that I didn’t sound so much like a jook sing as I did Singaporean. I have Singaporean friends, the academic discipline of geography is frighteningly strong in Singapore, and I love Singapore, but I am not Singaporean. That weirded me out. A few days later, over dinner, a professor criticized me for researching Christians in Hong Kong. He said that I’d be better off studying Buddhists. I replied that I wanted to study Christians because it was a diaspora project. He said that I was better than that, that ‘we Hong Kong people are not like those ABCs,’ American-born Chinese. I replied that I was an ABC. He was stunned into silence. I was too. I didn’t realize I had gone native.

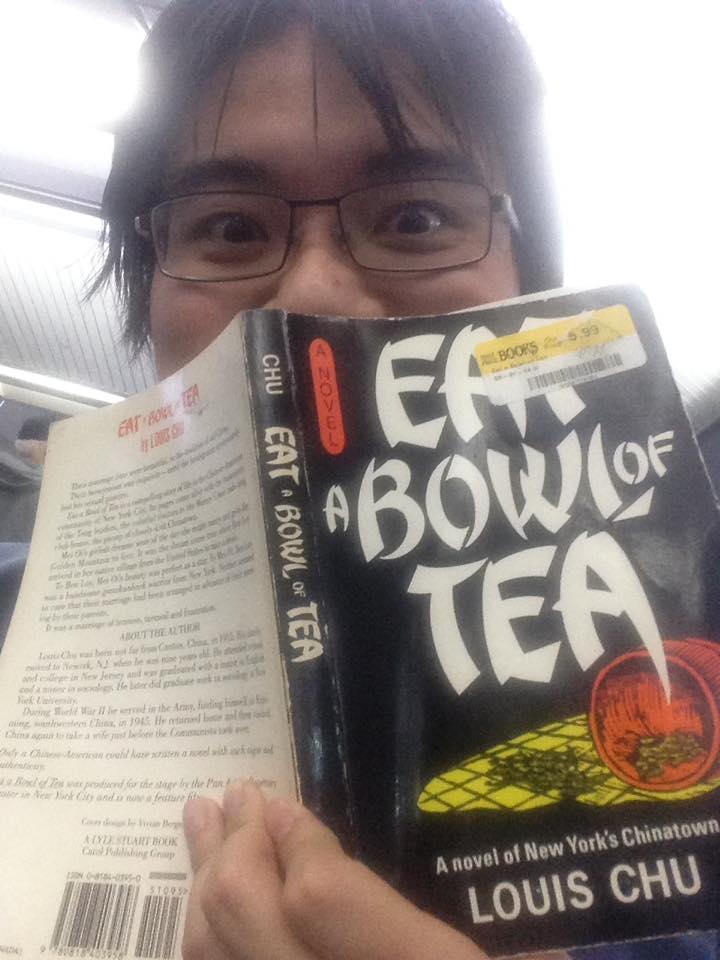

A few years later, I read the book Aiiieeeee! which put me onto Louis Chu’s Eat a Bowl of Tea. Reading too quickly, I misread the books as advocating a jook sing identity that was hollow and therefore enabled a negative sense of being ‘Asian American.’ I began teaching Eat a Bowl of Tea this way a few years after that in my Chinese American experience class at Northwestern. There, I was utterly decimated in the middle of lecture as I realized while reading passage after passage after passage that I had prepared that Chu (and the editors of Aiiieeeee!) were not advocating for a jook sing negative identity. They were criticizing it.

It turns out that ‘Chinese culture’ is not just about Confucianism. Frank Chin, the ringleader of the Aiiieeeee! editors, likes to refer to it as a ‘street’ sensibility of the people, one that includes Confucian wisdom but is really more about martial strategy, historical models of integrity, and a sense of brotherhood and sisterhood that defies gender boundaries at the level of everyday life. You don’t get it from reading Confucius; you learn it from opera and poetry – or if you’re like me, television and movies.

This everyday Chineseness permeates the comedy of Eat a Bowl of Tea. The protagonists Ben Loy and Mei Oi struggle through Ben’s erectile dysfunction. The hollowness of being a jook sing – Ben Loy sleeping with white prostitutes, Mei Oi being coerced into an affair through sexual assault that is not even acknowledged, both of them dreading disappointing the parental generation while rebelling against it in the realm of fantasy – is what causes the sexual problem. But by the end of the book, they are visiting herbalists for folk cures and living into the mythology of being warriors. They adopt Mei Oi’s child by another man because, as it is in Confucius, ‘family’ is not biological – it is whoever you’re doing right by under your roof gathered around the ritual table. They are also able to make a baby. Sex is not a problem anymore.

It’s that struggle that I hear in Julian’s slow, even mournful dirge. It’s the song of the folk, just him and a guitar. He’s lamenting the Jook Sing Cafe. He read this angstyness in my Cantonese posts, the ones that I wrote over the summer to process that disaster of a class (although I got surprisingly great reviews for it), and he wrote folk commentary on it. Make it sad, and lonely, and lovely, and long.

Julian is a PhD student at Brown University. He also hosts a multimedia concert called the No-No Boy Project, which he takes on tour at universities around the country. I think he said ‘Jook Sing Cafe’ is being added to the line-up. Actually, I’m sure of this because he’s asked for photos to go along with it. I’m on it, Julian.

The fascinating connection is that my contact with Julian was the daughter of a pastor who is renowned for his work in ‘English ministries’ in the San Francisco Bay Area, the jook sing congregations. Her dad was the guy I laughed with about Josh Harris when that drunk uncle at the wedding we attended together told me to kiss dating good-bye. When I was at a church retreat at the age of twelve, I stood up in answer to God’s call to ‘full-time ministry.’ Her dad placed his hand in a firm grip on my shoulder to pray over me. I do not know what that prayer means for me now that I am Eastern Catholic. Of course, it was not through this woman’s dad that I met Julian; it was through a separate connection through an Asian American religious studies network. But that too seemed, as the Calvinists say, providential.

In any case, I am grateful to Julian for writing this song. He saw deep into my struggle with this concept. Listening to his music, I feel like my thinking is developing too. Such is the joy of unexpected collaboration. I hate to say it, but it is like the Holy Spirit is working among us.