I am finding these days that whenever I write something, I usually get pulled despite my best attempts at discipline toward unexpected rabbit trails that I feel compelled to follow. Sometimes, as I was trained since elementary school, I have a plan – an outline, a mental map, or something – that I’m trying to follow. Other times, I just begin a piece and have an idea of where I want it to go. But usually, things do not end up the way they are supposed to go.

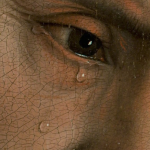

That pull, I am discovering, is that of the truth. It highlights the gap between my fantasies about how the world works and the world I am trying to describe. This is why writing is such a painful process for me: when I write honestly (which is only sometimes), the truth resists my attempts to advance my view of the world. It hurts.

I’ve been writing for a while now, and many of the ideas in progress have made it online in blog form. Some of them are more developed than others; a few are pretty half-baked. With the imports that were made as I began this Patheos blog from my pseudonymous work as Chinglican and my exploratory pieces on Religion Ethnicity Wired, the stuff that I have from the past five years is on here – in a way that, as my Patheos colleague Mark Shea puts it, ‘so that no thought of mine shall ever go unpublished again!’

There is some stuff that I lost from before that time when I took it offline and then my computer crashed, and I hope it is still on the deep web somewhere (Wayback, maybe?). There was a post on Lucy Pevensie on Narnia that I really liked (I still do), and then there was a piece I put out making fun of what was called the ‘Great Porn Debate’ that happened on my university campus in Vancouver, and there were even a few half-baked things on being a man in the newest of New Calvinist senses.

But as much as I tried to deny that I was trying out some academic ideas with Chinglican and Religion Ethnicity Wired (in one of my stupider passages, I wrote, ‘When I agreed to this blog, I swore to myself and by myself alone that I would never bring my actual academic work to bear on my comments’), the truth is that writing it all out has been helping me write more truthfully, which I think is what I am supposed to be doing not just as an academic, but as a person.

And thus, over the last week, I’ve been taking stock of some of the things that I’ve written and tried to write even more truthfully. What motivated this inventory-taking was my frustration at my attempt to say something about what happened on and around July 1 this year in Hong Kong. The problem is that I have a blog titled Eastern Catholic Person – not, say, Half-Baked Commentaries on Hong Kong – and as much as I tried to insist in my earliest posts that I was not interested in describing Eastern Catholicism as an ‘identity,’ that is exactly what I have been doing sometimes. I’d blog about trying to actually do what we call makrodiakonia – the large-scale service of the church to discern and challenge the structures of injustice in the world – but as I said at the end of that first post on Monday, it’s not like I’ve been very serious about it either. In trying to speak of the world, I could only speak in an insular Eastern Catholic way.

This didn’t feel right. Isn’t it the case that reflecting on Hong Kong is what brought me into the Greek-Catholic Church of Kyiv in the first place? Wasn’t it the practice of makrodiakonia that drew me into this ecclesial house? Didn’t I always intend for my writing to be from within the church toward the world? Isn’t this what it means to be truly Catholic – to practice tradition in a way that is not insular in a navel-gazing identitarian way, but is universal in its acts of personal love and wise discernment?

My intention, then, was to take stock of all of my online writing, even the stuff I put out before Patheos, to see where I had gone and how I wouldn’t end up back in that quandary again of wanting to write about Hong Kong and not being able to without a lot of throat-clearing. This is what that list of links at the end of Monday’s post was about – all the stuff that I had written in Hong Kong and that I wanted to develop further.

It turns out that that was just the first in a set of posts with a list of links. What happened is that that act of writing opened up a rabbit trail for me to explore. After all, in that first post, I had said that I am not from Hong Kong, even though I care a lot about it personally and professionally. But what did this mean? I began to ask. And thus, the next post on a Cantonese way of being in the world poured forth, followed by a corrective on my bad translation of 義氣 as the ‘air of righteousness,’ and finally culminating in my piece on being Cantonese in the colonized Kyivan church. The second and fourth posts were also followed by a list of links – one gathering all the stuff that could remotely be called ‘Asian American’ floating online, and the second with all my work on Christianity, colonization, and governance too.

The surprise was that all of it fit so well with my Cantonese inflections, even the stuff on the ‘private consensus’ and the legal apparatus. These are my words about the world, mostly developed as I worked through them intellectually in simultaneous Cantonese and English, and this way of working linguistically was the one thing that I had tried to get rid of in my writing, even as I wrote my entire PhD on Cantonese-speaking Protestants and their engagements with civil society and have started a second project comparing the origins and fallout of the Hong Kong Umbrella Movement to cognate protests and aftermaths in Kyiv and Seattle. When you’re a serious academic, you want to engage theory itself – and I have it all here on the blog, as I discovered: ‘grounded theologies,’ publics and privates, legal apparatuses and the practice of everyday life, political theology. You’re not supposed to use your own words, per se (even though everybody piously tells you that you should); you’re supposed to be hip and cool and trendy. But to invest my whole being into thinking, much as I professed to want to be intellectually chaste and to practice philosophia in the academy – that is a scary proposition.

I discovered while writing this week something that I’ve always known, but have been reluctant to watch myself commit to writing: it is that my way of being in the world is inescapably Cantonese. This is not a statement of identity – that’s too static – but it’s more like an orientation toward the world, a sensibility, a way of living ordinarily in my everyday life. It’s what my friend Sam Rocha calls folk phenomenology, an attempted description of how folks whose only point of reference is the truth of their own existence instead of some elite ideology that has been educated into them actually live their lives.

Sam’s frame of reference for the folk is the Texican, a Tejano (or as a Cantonese friend of mine once told him: You are Mesican! You like spicy! – Sam and I will never let this go). Sam describes his sensibilities about the world as having been nurtured in a region he still calls home, the borders of Texas and Mexico and didn’t really know the difference. There (and thus also here), he is someone who just picks up a guitar and knows how to play it, for whom Spanish is the language of the heart, for whom love for other persons that can only be described as erotic in the deepest of senses can make him go out of his way to do some ridiculous things. I have written about him before, and I’ve promised him that I’ll do it again with his next book; I have to keep this promise because of yi-hei 義氣, the spirit of integrity and loyalty. Sam is my friend; I know him well enough to know that he practices what he preaches, mostly because he has gone out of his way beyond doing ridiculous things for me to having me do ridiculous things with him.

Unlike Sam, I am not a Texican, although I recently revealed to him that I have had many Mexican friends in my life and that he is not the only one (I hope he was not too disappointed). My frame of reference for the same thing he is talking about is to be Cantonese from the American suburb. Cantonese is the language of my heart: my mother sang lullabies to me in that language, my grandmother stole a walnut from the supermarket for me with that sensibility, even my Shanghainese grandfather whose Cantonese was absolutely terrible played video games and told me folk tales with expressions like ‘aiyah, ho nga yeen ah‘ (哎呀!好牙煙呀! – ‘ah, so dangerous’ – by which all the Cantonese speakers here know that this is basically Shanghainese). My dad was the unpaid ‘minister’ (a title for non-ordained pastors in Chinese evangelicalism) of a Cantonese congregation in a predominantly Mandarin-speaking church. When I am frustrated, I speak in Cantonese, and when I am happy, I also speak in Cantonese. Cantonese food is my diet – not just the dim sum and rice that everyone thinks of, but meat cakes, butcher shop meat, sautéed vegetables, meat broth. I have to admit that I’ve been singing Cantonese songs since I was a kid, I love Canto-pop, and I’m afraid that one day I will finally get into Cantonese opera. Cantonese movies are a thing for me, especially the ridiculous Stephen Chow ones (I also did my B.A. honours essay in history on Michael and Sam Hui), and I do like the occasional Cantonese tv drama, even though I don’t follow them as religiously as some of my friends do. When my wife and I want to speak from the heart, more often than not, we are speaking Cantonese.

Sam’s Texican, my Cantonese, my church’s Ukrainian foibles – it would be imprecise in our liberal world to say that these are our identities, mostly because this is not the way that identity has been theorized in the world in which we find ourselves today (whatever the ancients, say, like Aristotle or Master Kung had to say about identity). In what’s called the politics of identity (at least as articulated by the Combahee River Collective), identity is an ideology that state, market, civil society, and informal institutions give you, telling you who you are in terms of race, class, gender, sexuality, disability, religion, and so on; what makes identity political is if you pull on those threads and say, No, you tell me this is my race, but I tell you that I am claiming my race for me now, not for you – for my experience, not for your impositions! Identity politics is claiming the very terms that an oppressive institution might use to fit you into their mould and then spitting it back in their face; intersectionality is about saying that there is more than one axis of identity-based oppression and that all of them need to be taken to understand the formation of a colonized self.

Folk phenomenology is something entirely different.

What Sam is saying, I think, is that there is a true way of existing that lies beneath all of our attempts to cover it up and make a world for ourselves with our own conventions and our own fantasies about how the world should work. That mode of existence – that ontology – can be described as personal, in the sense that I am a person not because I am an individual, but because you are facing me and I am facing you. This is very different from an institutional identity, one that abstracts me from my personhood and places me into a web of fantasies about how the world should work. It’s the deep structure of life, the messy reality that is what Michel de Certeau SJ calls ‘the practice of everyday life’ with all of its requisite legends, superstitutions, fables, and mythologies, the facing of each other that is universal in the sense that this is the primal ontology. It’s what Paulo Freire means when he says that only the authentic word spoken by the oppressed can transform the world; it’s what Gary Okihiro does in Third World Studies when he goes far beyond calling for an analysis of the ‘social formation’ of colonizing societies and tries to recover the mythologies that underlie the way that colonized peoples are oriented toward the world (his favourites are the Hawai’ian creation myths).

Sam’s orientation toward this deep truth is as Tejano. Certeau’s is the everyday joe schmoe walking the technocratic city in Western Europe and Latin America. Freire’s is the Brazilian peasant. Okihiro’s is the Hawai’ian creation myth. Hans Urs von Balthasar’s was the appearance of the glory of the Lord in the arts, literatures, and dramas of the Mediterranean region. James Baldwin’s is the American condemned to the core by American racial politics, Toni Morrison’s is the black woman whose love remains ambivalently chained to slavery, bell hooks’s is simply the human whose experience of love in the world requires a kind of freedom beyond the prescriptions of gender. Artur Rosman’s is a kind of dark Polish Catholic pessimistic romanticism. Mine is Cantonese. My church’s is Ukrainian – though it need not be because the Kyivan Church is indeed not a church for Ukrainians, but from Ukraine for the world. Yours might be something else.

The key is that there is this deep ontological truth about personhood, about love, about communion, one that is objective and universal and primal. It can be spoken of in our different accents, by our different foods, through our different myths, because these are the only voices we have: our own. But as my creative writing mentor Fr Harry Cronin CSC said to me years ago, The key to writing is to take a particular personal experience and make it universal; taking his own advice, he had done so in plays about the Holy Family, Irish Catholics, Iraq War veterans, and repressed gay men. To plumb this deep is to access a mode of existence that is more than the mere natural; populated with spirits and heroes and saints and gods and G-d himself, here we are, as my student Eugenia Geisel says, in the realm of the everyday supernatural, the deep structure of the world that has been given life by the very breath of G-d.

This is a truth that is supposed to hurt so good, as one of my students described my classes to me. The flip side of this reality is colonization, the attempt to educate this deep truth – this funkiness, as Sam calls it elsewhere – out of us so that we might be respectable. The reason I lost my writing voice is that I wanted to write respectably, fashionably, with sophistication.

This is why I’d say that my favourite book of all time is Louis Chu’s Eat a Bowl of Tea. I’ve described the hilarious plot about the main character’s impotence and the literally translated cuss words before, but my favourite description of the book is from the editors of the Asian American literary anthology Aiiieeeee! What I think they’ve written – but I’m sure they’ve told me personally – is that Eat a Bowl of Tea is one of these books that you read and you know you’re reading English words, but it makes no sense in English. It only makes sense in Cantonese – the inflections, the accents, the swearing, the food, the music, the poetry, the folk tales, the myths, the way of relating to each other and to the law and to the market and to societies outside of Chinese America. My ambition, I tell my students, is to be able to write in English with such a Cantonese flair, to be able to write so that all of my work – academic and popular – is accented in the way that I actually speak, with the orientation that I have toward the world. Some might protest that I am supposed to be a geographer, a social scientist; my answer is that Louis Chu was not some fancy-schmancy, highfalutin avant garde literary nutjob – he was a sociologist, a librarian, and a man who loved his wife and kids.

To write with a Cantonese accent – this is the surest sign that though I am born in Canada and raised in the United States and am supposed to be a jook sing ‘hollow bamboo,’ I am not at all assimilated. My universality does not lie in forgetting who I am, where I come from, and what my orientation is toward the world from my heart; it lies in seeing those particularities as themselves universal. This is, at the end of the day, what it means to Catholic – and indeed, what it means that both the Latin and Kyivan churches are equally Catholic and in full communion, what it means that I remain Cantonese and have not become ethnic Ukrainian by joining the Ukrainian Greco-Catholic Church.

Having taken stock of my online writing, I might have a better idea of what I’m doing as a whole, although I expect that I’ll write myself into more surprises as I keep going. The truth is – who am I trying to kid? I’m just a Cantonese boy from Ardenwood in Fremont who grew up walking to the pho place across the street for lunch and went to school in Hayward with a bunch of Filipino, Mexican, and Irish Catholics. And then I wound up in Vancouver, where I was actually born. Along the way, I kept on trying to deny the language, food, and relational sensibilities of my heart while it was woven into how I lived my everyday life, told stories, and even did theory in the academy and in my public writing. It is in Cantonese that I think about publics and privates, in Cantonese by which I am intrigued by both the law and the informal tactics people use to get around it, in Cantonese that I write about the fantasies that people have about the world versus how the world actually is.

It is thus in Cantonese that I practice makrodiakonia, my service to the world from within my church. I find myself in the oikonomia of G-d, and I will continue to write my enthusiastic posts about those practices too. But having retraced my steps, I have stories to tell and theory to do now, both here and in other venues. Don’t be surprised, then, if I write about worlds beyond my church. The church is where I receive the Holy Spirit, the spirit of righteousness, integrity, and loyalty – the true yi-hei 義氣 that is true wherever I go and about whatever I write. Without the Kyivan Church, I would be silenced, finished, paralyzed.

But there are two consecutive moments in my chrismation by which I knew I had come home. As I came into the sanctuary on the epitrakhil of my spiritual father, my biological father read the words of Psalm 66 (Septuagint numbering; 67 in the Masoretic text) in Cantonese:

願神憐憫我們,賜福與我們 ,用臉光照我們

好叫世界得知你的道路,萬國得知你的救恩。

神啊,願列邦稱讚你!願萬民都稱讚你!

願萬國都快樂歡呼;因為你必按公正審判萬民,引導世上的萬國 。

神 啊,願列邦稱讚你! 願萬民都稱讚你!

地已經出了土產;神─就是我們的 神要賜福與我們 。

神要 賜福與我們 ; 地的四極都要敬畏他!May God be gracious to us and bless us; may his face shine upon us.

So shall your way be known upon the earth, your victory among all the nations.

May the peoples praise you, God; may all the peoples praise you!

May the nations be glad and rejoice; for you judge the peoples with fairness, you guide the nations upon the earth.

May the peoples praise you, God; may all the peoples praise you!

The earth has yielded its harvest; God, our God, blesses us.

May God bless us still; that the ends of the earth may revere him.

I then approached the tetrapod and made a prostration, remaining on bended knees. Then a Polish Dominican from Seattle who was concelebrating the chrismation echoed the words of Scripture pronounced by Papa Wojtyła in Warsaw all those years ago:

Let your Spirit descend!

Let your Spirit descend!

And renew the face of the earth!

This earth!

There is a story of a student who, after finishing reading the Protestant theologian Karl Barth’s commentary on St Paul’s letter to the Romans, was so taken with Barth’s forceful, spirited, dialectical writing – ‘a bombshell in the playground of the theologians,’ as one critic described it – that he scribbled on the back page, Now I can preach again. In the same way, it is the Spirit’s descent upon me as I was received into the Kyivan Church by chrismation that I can write again – that I can be a geographer, in the sense that I write (graphos) about the earth (gē). I can only write the truth about it, and I can only write the way that I am, and the way that I face the world as one of its folk is Cantonese. But still, I can only write in synergy with the G-d whose energies make me alive, who turns his face to me in blessing, whose Spirit renews the face of the earth.

With such a conclusion, this is the final post in this series where I have committed afresh to writing Cantonese despite my usage of English, to write the truth, to write in the Spirit who renews the earth in the midst of the churches – including mine, the Kyivan Church – as we perform the works of makrodiakonia.

Glory to Jesus Christ! Слава Ісусу Христу! 榮耀歸給耶穌基督!