I come from a line of mothers who wander.

One of my maternal great-grandmothers, otherwise a paragon of Irish Catholic virtue, used to save up her housekeeping money and disappear for weekend drinking binges on regular occasions. During one of those absences, her daughter, my maternal grandmother Maggie, played a game of jumprope with a friend. Because they didn’t have a third, they tied one end of the rope to an old icebox, which toppled over on Maggie while she was jumping. She was concussed, but the injury didn’t seem to be lasting. Her brain was scarred, though, and 30 years later she developed epilepsy. Her grand mal seizures were treated, in those days, as madness, and she was frequently committed to an asylum. So while Maggie didn’t wander on purpose, the absences of her monthly “spells” and her regular commitments meant my mother grew up uncertain of her mother’s mental and physical whereabouts.

My other maternal great-grandmother, Susan, wandered in both senses of the word. While married to my great-grandfather, who was the coachman to wealthy Boston art patroness Isabella Stewart Gardner, Susan took up with another Gardner servant. She ran away with him, taking her baby daughter Mildred (whose paternity is questionable) but abandoning her three young sons, among whom was my maternal grandfather Bert. Mrs. Jack, as the formidable Isabella was known, reacted to the scandal and the inconvenience of having her coachman saddled with single-father duties by giving my great-grandfather a choice: keep his children or keep his job. He opted for the job, though he didn’t hold it long, and died homeless some years later in a notorious Boston flophouse fire. My grandfather, at the age of 12, was fostered out to a New Hampshire farm family named Pulsifer, who gave him love as well as work. He never forgave his own mother, or saw her or his sister again.

The legacy of these holes in the fabric of motherhood made my mother perpetually uneasy and fearful, prickly rather than cuddly, a critic rather than a nurturer, uncomfortable with change. She transferred her daughterly affections to the Blessed Mother, of whom she spoke with such homely familiarity that I grew up thinking of Mary as a direct relative. The icon of Our Mother of Perpetual Help in the parish church before which we prayed after Mass every Sunday, the Hummel statue of the Madonna of the Flowers that sat on the living room table (and now sits on mine), the reproduction of Raphael’s Madonna of the Chair that hung over the mantel–these were extensions of our family photo albums. When I sat as close to my mother as her zone of stiffness would allow in the pew at the parish mission and sang the hymn to Mary, Star of the Sea, we both cried, knowing what it was like to be the daughter and granddaughter of wanderers, thrown on life’s surge with no lighthouse but the Mother of Christ.

Hail, Queen of Heaven, the Ocean Star

Guide of the wanderer here below

Thrown on life’s surge, we claim thy care

Save us from peril and from woe

Mother of Christ

Star of the Sea

Pray for the wanderer

Pray for me

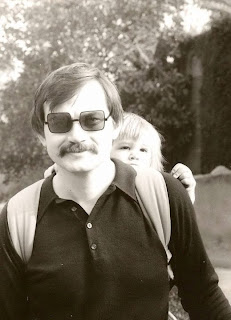

The line of wanderers did a 180 when it got to me. Motherhood turned what had been an occasional tendency toward panic attacks into full-blown agoraphobia. I loved my son in ways I couldn’t imagine loving, but I had zero maternal instincts and not one clue. The world suddenly seemed too wide, and terrible in its wideness. I wanted to be walled away in a safe little cell, confined in the frame around an icon. My pervading sense of dread, like my mother’s before it, was a Bad Fairy’s christening gift, and I have spent a good part of my son’s nearly 38 years atoning for the damage it did at the start.

Fortunately, God often provides. When a mother can’t mother, sometimes a father can. My son’s father did, stepping up and stepping in until my reason (or most of it) returned, leaving my son the gift of being a great parent himself. My grandfather, maybe with the help of Mrs Pulsifer, overcame his own loss and dealt with his wife’s disability. He was mother to his six children, keeping the family together through the Great Depression, and somehow transferring to my mother the late-blooming maternal ease that would make her the most caring and skilled of Nanas.

And sometimes, stepmothers are not wicked. My son’s stepmother has also struggled with agoraphobia, only hers has been lifelong and unremitting. In spite of that, in spite of how little she felt prepared to welcome an angry little boy and later a smartass teenager into the ordered cell of her world, she supported my son’s father and me, gave him another set of grandparents, made sure Santa visited Daddy’s house on Christmas Eve while father and son were at the midnight service, and sent my son and his father back home to my house for Christmas morning every year. On this Mother’s Day, I celebrate fathers and stepmothers, too.

Today, in addition to Mother’s Day and the Sixth Sunday of Easter and the Feast of Our Lady of Fatima, the Roman Catholic Church remembers a woman who did wall herself up in a cell–though never losing sight of the wide and terrible world of 14th century England for which she prayed–and who knew God intimately as both father and mother. We don’t know much about Julian of Norwich, not even her real name. She lived as an anchoress in a cell fastened to the side of the parish church of St Julian like a barnacle clinging to the side of a boat. She may have been a nun, but it’s quite likely she was a laywoman. She may not have been a mother herself, but she was a daughter. After undergoing an illness with both mental and physical torments, Julian began having visionary conversations with Jesus, which she later set down in what is considered one of the first spiritual works in English. Marked by homely directness and practical wisdom, Julian’s Showings celebrate God’s faithfulness as a parent who never wanders, an anchor of trust:

Christ our natural mother, our gracious mother, because he willed to become our mother in everything, took the ground for his work most humbly and most mildly in the maiden’s womb. . . . Our high God, the sovereign Wisdom of all, arrayed himself in this low place and made himself entirely ready in our poor flesh in order to do the service and the office of motherhood himself in all things. (Showings, Chapter 60)

Happy Mother’s Day to mothers all, and fathers who are mothers: to the wanderers and the anchorites, the workers at home and in the world, the frightened and the clueless, the helicopters, the ones whose nests are empty and the ones whose first eggs are about to hatch, the stepmothers and foster mothers and mothers-in-law, the Madonnas and the rest of us. As Christ our Mother said to his friend Julian in what then seemed the darkest days on earth, the time of Black Death when it seemed least rational to bring a child into the world, as Mary herself heard in the stillness of her heart, as all who “do the service and the office of motherhood” as best they can in every age proclaim:

“It behoved that there should be sin; but all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.” (Showings, Chapter 27)