We need to know ourselves to do philosophy, that is the lesson of Socrates. We must know our nature to be happy, that is the message of Philosophy. We must know God to incarnate, to live, either truth. That is Jesus.

We need to know ourselves to do philosophy, that is the lesson of Socrates. We must know our nature to be happy, that is the message of Philosophy. We must know God to incarnate, to live, either truth. That is Jesus.

The good news allows us to hear some difficult truths without despair. We can know Jesus and so know hope . . . nothing is so bad that we need to give up.

There is a hard truth that used to be a central feature of all education, classical, secular, and Christian, which many have forgotten. If most great Western societies were right about the nature of people and the nature of happiness, ignoring this truth might be the source of our growing sadness, anger, and depression.

We are blessed greatly, as Americans part of a powerful people, and many Americans have more opportunities for learning and enrichment than have ever existed in human happiness. I see no evidence we are happier as a result. Where my grandparent’s generation marveled at “having enough to eat” and had little trouble with gratitude for (relatively) simple lives, we want more.

Our schools and popular media do nothing to discourage this attitude. We want so much more than this Provincial life if we listen to modern Beauty and the Beast. Thousands of commercials wash over us urging us that we need stuff to be happy. The ancients, the wise of the Middle Ages, the Renaissance sages, the Enlightenment thinkers, would have (mostly) united to warn us that this would lead to misery.

Nobody “wins” if the prizes are money, power, or glory. Fortune does not last, because our physical life does not last.

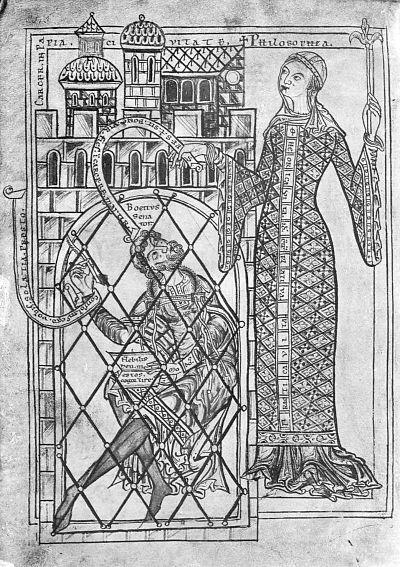

Instead, most of the great sages would have agreed with Boethius (the last Roman and the first man of the Western Middle Ages):

So true is it that nothing is wretched, but thinking makes it so, and conversely every lot is happy if borne with equanimity.

Boethius, Anicius Manlius Severinus (2004-12-11). The Consolation of Philosophy (Penguin Classics) (p. 31). Public Domain Books. Kindle Edition.

I suspect there are few schools in Houston that would dare to say this truth and fewer teachers and students that would believe it if it were said. Let’s avoid a first mistake: Boethius enjoyed the good things of life and did not like being imprisoned and losing those good things. What he is saying is that there is a deeper truth to the events of our lives, to the ups and downs of fortune and that this splendidly hard truth is that a good man can be happy anywhere.

History has shown that to be true. Nobody should experience injustice, but good men and women have made great art (like Boethius!) and faced tough times with resolve. Enslaved people like Frederick Douglass show that nobody should wish to be a slave, should escape if they can, but that a man like Frederick Douglass can never be a slave.

He faced his enslavement like a freeman, as a freeman he lived, and when he escaped, the outer reality came to match the inner truth.

We are not being told to cheer up about our sorrows, but to find a deeper happiness in eternal things. Classical pagan and Christian philosophy testify that this is possible. If we put our affections on things we cannot lose, then we cannot lose our happiness!

Boethius points out one obvious mistake: living for riches, jobs, or honors is foolish.

Have ye no good of your own implanted within you, that ye seek your good in things external and separate? Is the nature of things so reversed that a creature divine by right of reason can in no other way be splendid in his own eyes save by the possession of lifeless chattels? Yet, while other things are content with their own, ye who in your intellect are God-like seek from the lowest of things adornment for a nature of supreme excellence, and perceive not how great a wrong ye do your Maker. His will was that mankind should excel all things on earth. (p. 35).

We might reject mere money, but seek rank and power instead, but classical thought rejected this as a source of happiness. That is not, perhaps, the message we convey in honors classes and through media! Winning in politics is not a sign of blessing or victory:

‘Besides, if there were any element of natural and proper good in rank and power, they would never come to the utterly bad, since opposites are not wont to be associated. Nature brooks not the union of contraries. So, seeing there is no doubt that wicked wretches are oftentimes set in high places, it is also clear that things which suffer association with the worst of men cannot be good in their own nature. (p. 38).

In fact winning or money, can expose vice! Ask many a lottery winner:

And yet wealth cannot extinguish insatiable greed, nor has power ever made him master of himself whom vicious lusts kept bound in indissoluble fetters; dignity conferred on the wicked not only fails to make them worthy, but contrarily reveals and displays their unworthiness. (p. 38). P

Nero was a Roman emperor and James Buchanan President of the United States. The best men do not always get power! Power does not make a person happier. We must seek happiness and if power comes, use it wisely. Boethius was a political man. He was not afraid of power, but he saw that power could not make him happy.

This does not mean a worship of powerlessness! Powerlessness can no more (in itself) make a person happy than being powerful! Just as being poor may help us avoid some temptations to sin, it too does not make a person happier in and of itself. If our poverty forces us to eternal things, the Kingdom of God, then poverty can be a blessing, but I have known rich people that have had their prosperity also turn them to the Kingdom.

Classical and Christian education has long taught us to know our place. We can contemplate great things, but we are not so great! Our Earth is not (after all) such a big deal, so that even we could control all of it, that would be nothing:

The whole of this earth’s globe, as thou hast learnt from the demonstration of astronomy, compared with the expanse of heaven, is found no bigger than a point; that is to say, if measured by the vastness of heaven’s sphere, it is held to occupy absolutely no space at all. (p. 40).

(By the way, this passage alone from a classical and Christian writer should tell you what a lie it is to say that “modern science” with a “tiny Earth” was hard on Christians. The minute you hear a person utter such nonsense, think of this passage from one of the most read books in the Middle Ages and know it is a lie.)

Once we gain the idea that the eternal must be our goal for happiness, we might confuse “fame” or “glory” in this life for a source of happiness. Fame is fleeting . . . even if your book lives as long as Boethius:

So it comes to pass that fame, though it extend to ever so wide a space of years, if it be compared to never-lessening eternity, seems not short-lived merely, but altogether nothing. (p. 41).

Recall, a man or woman of character can make any situation a place for goodness. Evil men can do evil to us and that evil will harm them, but we can be sanguine in the face of that evil for our own happiness. In fact, classically, there was something good that came from “bad fortune:”

For truly I believe that Ill Fortune is of more use to men than Good Fortune. For Good Fortune, when she wears the guise of happiness, and most seems to caress, is always lying; Ill Fortune is always truthful, since, in changing, she shows her inconstancy. The one deceives, the other teaches; the one enchains the minds of those who enjoy her favour by the semblance of delusive good, the other delivers them by the knowledge of the frail nature of happiness. (p. 43).

The Bible makes this point: good times are good, but can be bad for us as they can tempt us to love the good things! Recall: we are not called to pretend bad times are not bad, but to transform them (as we can) into something better. We must never make the mistake of telling other people to do this, lest we become Job’s friends. Instead, this is a call from Philosophy to me.

We also cannot wait to train ourselves until the hard times. Good times will confuse us into thinking that our enjoyment of temporary goods is the source of our happiness. We will not hold these things with a light hand, but grasp them and hate our life when they are gone. This is why classical schools trained students in a kind of stoicism and Christian schools taught us to look for higher things.

Heaven is my home. I am free. I am God’s child. I will enjoy temporal things when they come, but as a signpost to eternal things: ideas, souls, and God.

There are two mistakes that I am tempted to make at this point. First, to think that good and bad deeds in this life do not matter at all. Of course, they make us sad We see people doing injustice or tyrants and our soul cries out for God’s Kingdom to come. We are perfectly capable of having two emotions at once: we would prefer this tyrant be defeated, but if he is not then we will not be defeated. We will be liberated even in death!

Second, I should not withdraw from life, especially business and political life, just because I cannot love money and power. A person can enjoy a thing to the extent it can be enjoyed or seek a thing for a good purpose without making it an idol. If I will do anything, for power, then power is an idol to me. However, God can give us power and we can hold it lightly! If I love money, this will be root of all kinds of evil, but God might give me money to enjoy and do good.

We must not over learn one truth and forget another. We must not give up on an idol only to set up a weird idol of our not having that idol! We must not worship poverty to avoid the love of money. We can be rich or poor. We can be sick or healthy. We can be happy and content in all things. Maybe we all need to find a community, church, or school that will teach us this:

So true is it that nothing is wretched, but thinking makes it so, and conversely every lot is happy if borne with equanimity.

—————————-

Based on a class taught at The Saint Constantine School. Part I is here.