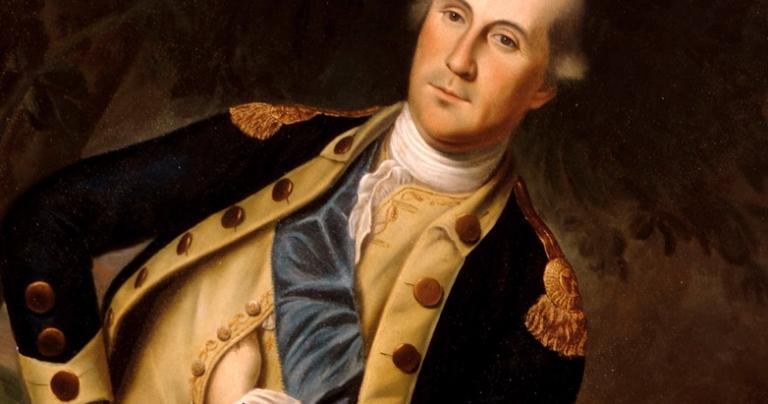

George Washington went home. That’s the greatest thing he did and is remarkable in human history. He was the man who kept the Revolutionary army in the field and whose integrity made the Constitution possible. Since Washington would be the first President, the Founders were willing to create a stronger presidency.

Washington knew everything he did was a precedent for lesser men who would come later and so he went home after two terms. Nobody could break that precedent until Franklin Roosevelt and then the nation amended the Constitution to keep it from happening again.

Washington knew everything he did was a precedent for lesser men who would come later and so he went home after two terms. Nobody could break that precedent until Franklin Roosevelt and then the nation amended the Constitution to keep it from happening again.

Nothing so becomes a powerful man than giving up power. My mom and dad have followed this model and my goal is to do the same. One reason I moved on from being director at the honors college I helped found was that the time comes for the founder to move on, so that a precedent can be set for a change of leadership without a change in vision.

A leader knows that he must serve people and not be served. He also knows that leadership will drag him away from other interests and tasks that are often more important. Good people have lives apart from leadership roles. Washington loved his home, Mount Vernon, but duty kept calling him to leave. You could not have paid him enough to tempt Washington to be President and by that time in his life he was already one of the most honored men on the globe. He did not need the job, he took it out of a sense of duty.

Instilling a sense of duty in a future leader is vital, because it prods a good man, who does not need to be a leader, to do what he must. A man like Washington would feel shame if he lived in ease while his country suffered. An even better man would be ashamed to ignore the call of the nation even if he otherwise was busy pursuing goodness, truth, and beauty! Leadership is not the highest calling, but somebody has to do it and the people who cannot wait to lead, need to lead, or cannot imagine not leading are dangerous in power.

This Christian idea is shared with many classical philosophers.

Socrates (in Plato’s Republic) describes a great leader as needing to be “induced” to take office by positive and negative prods:

Thus a man must be induced to take office by wages in the guise of money, honors, or-in case he still resists-by threat of a penalty for refusing to serve.

Many will think of the penalty for not serving on a jury, plenty “serve” only to avoid the fines, but this is not the kind of person Socrates means. Serving on a jury is an honor, a powerful position that citizens gained after great struggle. When I do not wish to serve because it might inconvenience me, I am not being a good citizen! Instead, a better person would realize the power of sitting in judgment, the chance for mistakes, and not feel fit. We should say: “Who am I to judge?” God forbid a jury be made up of people who cannot wait to sit in judgment.

All of us (certainly me) should hesitate over power, because power is so hard to use well and because while we are sitting in administrative meetings we are not doing the human activities that make the biggest differences. No teacher should rush to be a dean. Imagine a college president or administrator who was not eager to teach or do research! Perhaps no college should hire a person who applies for the job! Instead, (God help me!) our motive must be to empower and enable the folk doing the real work. Our politicians should be making society more just, so that justice can be done! They should never confuse creating the conditions for justice with creating a civilization.

Leaders serve so that everyone else can do the real business of living: human flourishing!

———————————————-

*I begin an informal summer reading of Republic using Scott/Sterling (a new translation for me). Part 1. Part 2. Part 3. Part 4. Part 5. Part 6. Part 7. Part 8. Part 9. Part 10. Part 11. Part 12. Part 13. Part 14. Part 15. Part 16. Part 17. Part 18. Part 19. Part 20. Part 21. Part 22. Part 23. Part 24. Part 25. Part 26. Part 27. Part 28. Part 29. Part 30. Part 31. Part 32. Part 33. Part 34. Part 35. Part 36. Part 37. Part 38. Part 39. Part 40. Part 41.