Don’t just talk, do things. Do not just do things, talk and then do things.

I have worked at places that saw a problem and set up a committee. When they saw they had too many committees, they set up a Committee about committees. They are talking themselves to death.

That tempts many of us just to act: just do it. This chokes off other voices, does not give time for data collection, and multiplies error.

Here is a shock: we can talk and do. We need balance, yet anyone engaged in liberal arts education must admit that there is a tendency to jawing a problem to death. We suffer from administrative bloat and our windiness fouls the air.

A liberal education goes bad if it becomes detached from doing things: work. Discussion must continue, because the world changes, but discussion that goes no place is useless. In this light, I am going to respond to a letter from a very thoughtful reader who works for an excellent liberal arts program.

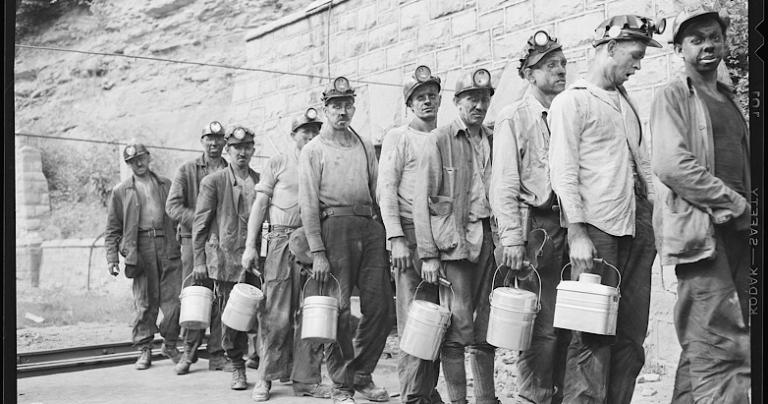

Here’s the issue: There is a prima facie tension between the nature of liberal education (or at least the way in which liberal education frequently is described) and the theology of work (TOW). The TOW highlights the intrinsic goodness and value of work—indeed, the fact that humans are created to work. Let us grant that. Education in the liberal arts, however, often is distinguished from “vocationalism” (training for a trade/work) as being education rather than mere training; the former is said to be of intrinsic value, while the latter is said to be of merely instrumental value.There’s no formal contradiction, of course, but there seems to be an implicit tension between the two. This is evident particularly in certain older books on liberal education, which treat vocational/professional training somewhat dismissively (if not derisively). What I am trying to think through is how to articulate (specifically in a Christian context) the interplay between liberal education and the TOW. Russell Kirk says that “the higher aim of man…is the object of liberal learning,” and I don’t necessarily disagree. But I also agree with the TOW claim. May I ask for your thoughts on this? How do you understand the relationship here?

Before answering this question, let me highlight an agreement: there is no formal contradiction here. A good liberal arts education should prepare the soul of a man for work and for living in Paradise. Any good theology of work will describe what a man will do here, value that effort, and speculate about the role of work in the life to come.

The tension exists, because liberal arts colleges grabbed vocational training when we should not have done so. Nursing is a good example. Instead of leaving nursing training in hospitals, where the trainees could be paid, we acquired this training, charged a great deal of money for it, and still tried to squeeze in a liberal arts education. As college grew more expensive and more people came to college “to get jobs” those of us trying to continue giving a liberal arts education grew defensive. We were doing an important job, but not the task people would pay big money (or accrue big debt) to get. This was and is proper: liberal arts education is not expensive, but by marrying it to the administrative system, job training, and professionalized sports we made it costly.

This tempted our “customers” (God help us) to measure our worth in money. Why not? We were and are charging enough.

As a result, I know a Christian university with a first rate liberal arts program that they tout as a flag ship of the University that is trimming the liberal arts by cutting required units. They homogenize curriculum, something foreign to spiritual formation, and rely on part-time professors. They must.

The temptation to attack “mere” vocational training is natural, but must end. This is caused by an unwholesome conflation of vocational training and liberal arts education.

The critics in vocational training point to the expense and time of liberal arts education. The liberal arts educator feels compelled to sneer at “mere” vocational education. Nobody suggests the natural and wholesome solution that liberal arts training be set free and allowed to charge what it costs (about twelve thousand a year) and/or allowing vocational training to also be set free to do that valuable job.

Both should lose the costly “student life” and administrative components. The next time you are visiting a college or university, ask the President what he or she makes. Ask if he or she receives a salary from a “for profit” parallel institution to the University and what benefits (housing, car, servants), he or she receives. Ask how many vice-presidents work at the school and the average salary of those vice-presidents. You will understand a great deal.

Liberal arts education reacts by trying to prove monetary worth. This exists, but is already giving up the game. We are educating whole souls and if that makes money (as doing well often does), then excellent. If it makes martyrs, as spiritual formation can, then so it goes.

Liberal education deals with the inner man and that makes a better outer man. However, the theology of work reminds us that craftsmanship, scientific methods, and practical training are necessary too. A lady or gentleman who cannot program is not going to make a great computer programmer without training. In fact, resistance to learning usable skills to help one’s neighbor is a sign that one has become a drone (at best a Bertie Wooster and at worst a mere boor). A liberally educated person should long to have a usable skill to benefit people.

How not?

My modest proposal is to value both. We need not be revolutionary in present systems that contain much of value. Let’s cut the tuition in general education radically and expand offerings. People can pay who wish for it. Let’s charge for work training in a manner that reflects the marketplace. We need to stop having one tuition cost for expensive programs and the same for the interpersonal and inexpensive general education training.

Those of us in the liberal arts can teach, cause no debt, and so the benefits will be obvious. We need not, should not, and then will not be tempted to put down our expensive (usually better paid) colleagues in career training programs.

A liberal education makes a person fit for work and work reveals who really received a liberal education.