“Don’t you want to be free?”

“Don’t you want to be free?”

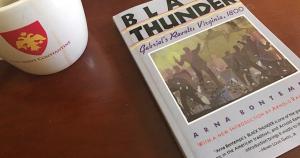

That’s the question the enslaved people of the United States ask in Black Thunder, a novel that should be read by anyone who cares about the answer to the question.

Arna Bontemps, a product of Christian education and the Harlam Renaissance, was bold enough to write a novel where powerful African-Americans said: “Yes.”

He wrote in 1936 Los Angeles, Watts, when the Civil Rights movement was still thirty years away. Bontemps wanted to be free, even when those who should have proclaimed liberty were too cautious to do more than mutter moderation.

The novel is based on an actual rebellion of enslaved people in Virginia that came tantalizingly close to repeating the amazing liberation of Haiti from slave culture. The battle for freedom failed, the weather, if not the stars in their courses, wiped out any chance for success. A once a century rainstorm saved the slavocrats for a few more decades, a chance to repent before the apocalpyse, or if in the hardness of their hearts, they doubled down on tyranny so the judgment of the good God could be even more fierce.

Bontemps’ created a hero from the history knowing history killed him, false victory of tyrants. The doom was coming as Lincoln expressed:

Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.

Gabriel, the hero of the novel, is fleshed out from the too little that history recalls of this freedom fighter by Arna Bontemps. Most of the characters are complex, though the women are less successful as fully realized humans than the men. This is novel of men created in the image of God refusing to be less than God made them.

An Injured Man, but a Man

The voices of the novel are almost entirely of the African-Americans who wanted to be free to death, some who wanted freedom, but were afraid of the cost. This is just, because the story of slavey is the story of people who were born free, but were put in chains by the sin of American slavery.

The enslaved are not portrayed as perfect, they are men not angels. The slavers are not devils, they also are just bad when they might have been good. The critical fact is the enslaved were men and once the brave people of Haiti gained freedom, the game of race based slavery was over. Napoleon lost to black men before he lost to Wellington.

The enslaved men put fear in the hearts of even a genius like James Madison, governor of Virginia, at the time. How could this be? Madison was, in many ways, a great man, but Gabriel, the slave revolutionary, reduced him.

As a slaver, Madison became less than a man as any man is who would be a tyrant. Plato knew it.

The slavocrats, especially the revolutionaries like Jefferson and Monroe, were utterly inconsistent. They said all men were created equal, but then denied that God had given the right to liberty to millions of men. The inconsistency stank and undercut the glory of the American Revolution as surely as the Terror destroyed the glory of France.

One white man in the novel puts it this way:

”I can well understand how men’s startled consciences make cowards of them. They recognize in the Negro a dangerous man, because they recognize in him an injured one.”

This is true, as far as it goes. What the white men in the novel cannot see is that the injury is not where the power and strength comes. Instead, it is the manly nature of the strong, black man Gabriel and those like him that gives strength.

The white man is guilty, Gabriel is a man. That’s enough.

Anyone Will Want to Be Free

Do you want to be free?

That was the question then to each one of us. Those waiting to be made free will never be free. Those like Frederick Douglass or Arna Botemps cannot be slaves, because they will to be free.

The slavocrats could not enslave Douglass, the Great Depression could not keep Bontemps down. The church let Bontemps down and he left, but the deep truths of the faith never left Bontemps.

He kept proclaiming liberty, not just throughout the land, but in the hardest place of all: in his own soul. Bontemps would not settle for anything less than freedom.

Bontemps was a novelist, poet, children’s author, and scholar. White American Christians gave him education, jobs, but would not give him freedom. When the Depression came, liberals in New York abandoned the Harlem Renaissance. Yet when Bontemps began intellectual exploration, the Christians he knew were not able to allow his soul liberty.

Yet Bontemps did not cease from mental fight. He was free and he lived just long enough to see better days. The job is not done. The question is still asked to all of us: Do you want to be free?

There is another question implicit to those who have power: Do you want us to be free?

There can be no stability, no justice, until all God’s children are free.

God help us all.