Knowing how to read old books is hard work. Harder still is the work scholars do to make old works in other languages ready for us to read. Scholars translated the books of the Bible for us from such ancient manuscripts and I am in awe at the work they do.

I am happy I get to see some of that work every time I read the English Bible (or even the Greek text).*

A great thing about almost every English Bible is that the translators have shown us some of the science and art of translating an old book.

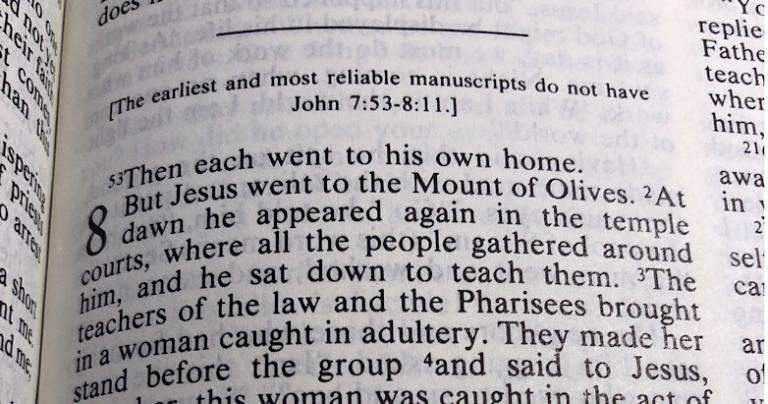

If you are reading the Gospel of John, for example, almost every Bible on my shelf of translations (all but one pew Bible) will point out that the “woman caught in adultery” story does not appear in the earliest manuscripts of John.

What do you make of that? Talk about it if you care, but notice that nobody is hiding the “problem” from you. Most Bibles will point out alternative readings for passages or tell you where the translators have made a choice that was contentious to the group of translators.

What the Bible is for

This openness is an important strength of the vast majority of Christian groups. No significant group of Christians thinks there is an untainted, perfect copy of any Bible book. Why didn’t God preserve one?

That’s an interesting question, but begin asking with the fact that if you thought there was one perfect Bible copy, your own copy of the Bible was telling you that you had misunderstood the Bible and the function of that text in the Church.

This is not putting down the role of the Bible in Christian life, God forbid! Instead, it is reminding us of what we all know: God so loved the world, God sent His Son. He did not preserve a single original written record of that coming.

This is not news. Those of us who are lay readers of the books of the Bible knew it because we have always been shown it in our Bibles.

The “problem” of John 8

If one looks at the books of the New Testament, even a layperson discovers that we have complete copies as early as the fourth century. Compared to other ancient books such as Plato, my own specialty, that is very close in time to the autograph. We have fragments—though not complete books—of Scripture dating as early as thirty years of the original. We have important Church figures quoting the books of the Bible from very early in Church history.

No reasonable person thinks that we do not have what the original authors wrote. This is not based on religious belief, dogma, but on the same science and scholarship of ancient manuscripts used in every ancient book.

Take a book like the Gospel of John. It is a whole and there is little doubt that whoever wrote it, wrote about sixty years after Jesus died. Why? We have a complete manuscript relatively close in time to the autograph, a fragment of the Gospel (matching the text) from thirty years after the Gospel was written, and many references to and fragments of the text between the time of the earliest fragment and the complete Gospel.

Imagine, however, that a modern Bible contained a bit not found in the ancient copies or not supported by the fragments. We don’t have to imagine this situation, because that is the story of the woman caught in adultery in John 8. Unlike the rest of the text, there is not a good reason to think the story was in the original version of the Gospel. That’s why it is bracketed. Scholars debate the status of the story, but for the layperson, the safe bet is to not base too much on this disputable account by itself.

Notice that the end of the Gospel of Mark is this way as well. Your Bible has always told you so.

Don’t make this mistake

There is one utterly shoddy argument that nobody should make: early fragments that match the text do not confirm the whole, but only themselves! Instead, when you have a whole that reads as a whole and scholars find earlier fragments, and these fragments agree with the passage that exists in the whole, then this is taken to confirm the very high likelihood we have the text as it was written. John 8 and the end of Mark show that this does not always lead to positive results for stories or passages!

When I was working on Plato’s view of the human soul, there were problematic passages in Timaeus that were difficult to square with other things Plato wrote. “What if,” I thought, “they were not in the original?” After all, our manuscript tradition for Timaeus is much weaker than for the Gospels. My advisor rightly stopped that sort of foolish thinking.

The Timaeus is a whole and our manuscript is well attested with numerous citations as early as Plato’s student Aristotle. Just because one particular passage is cited much later in time does not mean I should doubt it was in the original text.

How to know when the text is authentic

Now, if an entire section, like the story of Atlantis, had been missing from all ancient fragments or references, this would begin to be grounds for challenging the section (just like the woman caught in adultery) as in the original—though the book’s smooth transitions would make even that argument difficult to sustain. The fact that a particular line or section in the whole is attested later is interesting to observe and might tell us something about what ancient commentators found interesting, but does nothing to challenge the place of the passage in the book.

Some scholars, due to theories they had about the development of Plato’s ideas, tried to date the text as coming in the middle years of his career instead of being one of his last books. That has mostly failed as the ancient testimony puts it near the end of his life. Notice, however, that overwhelmingly what scholars did not do is to simply dismiss the troubling passages (to their ideas about Plato) as interpolations. There was no good reason to do so.

In the case of the New Testament, a scholar might disagree with Paul in his arguments in Romans, but we know, almost surely, what he wrote. On top of ancient fragments that confirm the text, we have citations in other ancient books that confirm that the text we have is accurate. Go read I Clement where he cites Pauline epistles. Where scholars are not sure, a good English Bible will let you know. This year try delving into the “helps” of your English Bible and learn the nature of the text we have!

—————————————

*Any of the Greek texts (classical, Christian, or later) in my office are based on the hard work of scholars who give me (in Greek) the closest thing they can to the original. It is not translated (good news!), but is not just “what Paul or Plato said.” This is obvious from the textual variants.

Here is a general rule: the more manuscripts (evidence) we have, the more variants there will be. Up to a point, having more notes about alternatives is a sign of strength. Sadly, a book like Timaeus, for example, has a very limited textual tradition and so fewer notes.

Rachel Motte edited this essay and added the sub-headings.