Specialists develop professional language to shorten conversations with each other and to achieve precision in complicated arguments. Gone wrong, however, this can turn into jargon where things that could be said simply and precisely in plain English are made obscure, often so the speaker can bloviate without fear of contradiction.

Specialists develop professional language to shorten conversations with each other and to achieve precision in complicated arguments. Gone wrong, however, this can turn into jargon where things that could be said simply and precisely in plain English are made obscure, often so the speaker can bloviate without fear of contradiction.

Sometimes those of us who are lay readers of theology find writers that needlessly complicate (Tillich), leaving us the suspicion there is little sound to the noise ration, but there are also dense writers (Barth) that have so much to say that a technical vocabulary is necessary to keep a long exposition from becoming even longer.

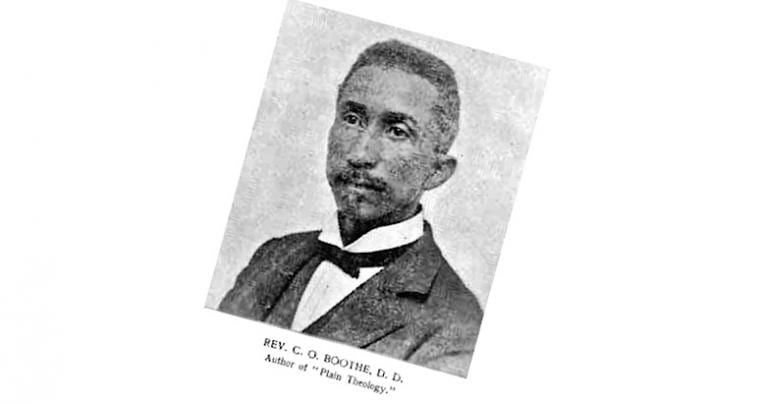

Thank God for thoughtful expositors who lay out the main ideas of Christianity, plain theology, for plain people. God bless them. One of the best is Charles Ocavius Boothe (1845-1924) whose theology is orthodox, but whose perspective was shaped by being enslaved and then liberated. He approaches the being and character of God with a different perspective from a rough contemporary like the Yalie RA Torrey. Evangelicalism was born in the work of Torrey and Boothe. Their commonality is great, but differences are also interesting: orthodoxy in different voices. Here is the voice of Saint Paul in II Corinthians 6: 1-10:

We then, as workers together with him, beseech you also that ye receive not the grace of God in vain. (For he saith, I have heard thee in a time accepted, and in the day of salvation have I succoured thee: behold, now is the accepted time; behold, now is the day of salvation.) Giving no offence in any thing, that the ministry be not blamed: But in all things approving ourselves as the ministers of God, in much patience, in afflictions, in necessities, in distresses, In stripes, in imprisonments, in tumults, in labours, in watchings, in fastings; By pureness, by knowledge, by long suffering, by kindness, by the Holy Ghost, by love unfeigned, By the word of truth, by the power of God, by the armour of righteousness on the right hand and on the left, By honour and dishonour, by evil report and good report: as deceivers, and yet true; As unknown, and yet well known; as dying, and, behold, we live; as chastened, and not killed; As sorrowful, yet alway rejoicing; as poor, yet making many rich; as having nothing, and yet possessing all things.

As a Western person who has joined an Eastern church, hearing how the same doctrine expressed differently is my life: fascinating and illuminating. The truth is easier to see from many perspectives and voices. Writing to sharecroppers or others hungry for the truth but cut off from formal education, Boothe gave himself the task to speak the truth beautifully and faithfully. Just the task shows that the intellectual snobbery that says such doctrines are unnecessary to the “less educated” is a lie. Everyone who loves God wants to know about God, because every person in love wishes to know the Beloved. Nobody wants to love badly through ignorance.

Doctrine is for everyone who loves God known through Jesus. The Bible was a liberation as slavers knew. This is why they created a slave Bible: the whole Word of God was dangerous. Let a bright young man read and he would change the world:

As a teenager, Boothe worked as a clerk at a local law firm. He explored Scripture on a regular basis, because mid-nineteenth-century legal practice was rooted in biblical logic.

Boothe begins with the being and character of God and surpasses Torrey in his clarity. This is a wordsmith, making the rough places plain, not an anti-intellectual:

These remarks are by no means intended as criticisms upon theologians or upon the theological works extant. All the writer means to say is this: There are people who live on a plain so far beneath the mental heights of these works as to be unable to reach up to them and enjoy their spiritual blessings. For these people there come to us calls for the preparation of special works—calls which, in the name of Christ, we must try to answer.

He says:

Before the charge “know thyself,” ought to come the far greater charge, “know thy God.” But, though the study of the being and character of God is a duty which we dare not disregard, still, let us not be unmindful of the fact that we vile, short-sighted worms should approach the solemn task of studying God with feelings of humility and awe. God is found of the lowly, but hides himself from the proud and self-sufficient man. When Daniel fasted and prayed and made confession of sin, the secrets of the Lord were unfolded to his view.

Socrates assumed something he should not have that Christian thinkers like Boothe saw: knowing self, knowing one’s cosmic place, and beginning with First Causes, First Being: God. Boothe moves from Creator to Divine Providence quickly and makes a distinction that would save many budding apologists from mistakes:

The vulgar will call it luck, unbelievers will call it chance, but deep down in each heart there remains the feeling that in verity there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of in common philosophy. . . . For whether we are manly enough to confess it or not, we all, at times, feel with Shakespeare—“There is a divinity that shapes our ends, Rough-hew them how we will.” Let it not be forgotten that I am contending that then.

There is such a thing as a general as well as a special providence; there is the supervision of the works of creation, especially of the intelligent creation.

A people being hindered by a tyrannical majority could appeal to the moral law found in Scripture:

This law demands that men shall worship God and love one another, neither of which principles have origin in the depraved nature of man.

Boothe is Bible centered, as he should be. Whatever our tradition, the Bible is the universal fountain freely available to all. No stream is independent from the Bible and because the text endures, error by way of unwise innovation is made more difficult. All truth is compatible with the Sacred Scriptures or it is not truth. Boothe brings the plain people the plain truth of Scripture.

Even in Trinity, hard to explain in plain language, Boothe finds Bible teaching:

Here I speak with rather more fear than usual, and yet I speak; for the holy book has spoken before me. The doctrine declared here is that God, who is one in substance and one in character, exists in three persons, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. I would observe that this doctrine is revealed to us in the Sacred Scriptures.

He is careful enough not just to argue his case, but to point out where dissent exists. Perhaps, the use of “we” in Genesis when God creates is a hint of the Trinity, but perhaps not. Boothe gives the truth, plain truth, without covering up all the “maybe” that exists at the margins.

Boothe gives his plain reader an overview of the nature of God that can be filled in for the rest of the life of the reader and student. That’s hard to do and he does it well.