American Christian history has a powerful Reformed strain. Often other Christians, even those of us in the Orthodox Church, react to the Reformed American story and so it benefits us to know it. After all, most Americans have been and are some sort of Christian and our first intellectuals, men like Jonathan Edwards, were Reformed.

American Christian history has a powerful Reformed strain. Often other Christians, even those of us in the Orthodox Church, react to the Reformed American story and so it benefits us to know it. After all, most Americans have been and are some sort of Christian and our first intellectuals, men like Jonathan Edwards, were Reformed.

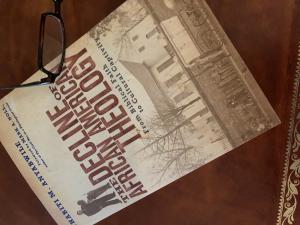

Thabiti M. Anyabwile is a Reformed Christian, very much so, and he sketches a history of African American theology from that perspective in The Decline of African American Theology. As Mark Noll points out in the introduction to the book, the clear perspective gives the book focus and so allows much work to get done in a short space.

This is an admirably readable history: scholarly without academic jargon. Just as Reformed Christians have been here from the start, so have African-American Christians. Anyabwile sketches what the subtitle to the book calls a decline “from Biblical faith to cultural compromise.”

The book is vital: American Evangelicalism and Pentecostalism is heavily African-American. The influence by African-American thinkers and ministers in Pentecostalism, for example, is immense. No history of the charismatic or Pentecostal movement can ignore Azusa street and when I went to a Pentecostal Bible college in the 1980’s, it was widely believed (and taught) that the segregation of the movement helped kill it for a time.

The essential drift of African-American theology was toward cultural compromise and with that compromise came a loss of creativity. African-American faith, ideas, and practice created church musical forms, ideas regarding the work of the Holy Spirit today, and the role of justice in the lives of the faithful. If Anayabwile is correct, and his argument while concise is overpoweringly annotated and careful, then this influence declined as African-American religious communities began reacting and adapting more to American culture than the Word of God.

This decline in part came because much of white traditional Christianity cared more for white supremacy than the religious values they touted. Seminary doors were shut in “conservative” places. The traditional views of African Americans in theology eventually faced the fact that white supremacy was more important to most traditional Evangelical institutions than traditional Christian ideas.

Meanwhile, “liberal” seminaries had many vices, including their own cultural assimilation, but white supremacy was not as dominant. African-American students could attend. This had a natural impact . . . just as Soviet era outreach to African university students shaped a generation of African leaders.

The pernicious impact of white supremacy is difficult to over estimate.

World class thinkers like Howard Thurman moved to privitize faith and place less emphasis on the authority of Scripture.* He found willing mentors in the rubble of the religious “burned over district” of Upstate New York. Thurmun kept private experience, but fell into the “BOMFOG” of the time: religion amounted to the “Brotherhood of Man and the Fatherhood of God.”**

Professor James Cone developed Black Theology centered on liberation that came out of this move to the left. This is dealt with in detail in the important text by Dr. Anthony Bradley. Nobody should begrudge the energy and temporary relevance this gave theology in general and all of us are thankful for the awakening of the conscience of the nation. Sadly, as victories were won in the area of justice, the reactive element (against injustice) left Black Theology less culturally rich than the earlier African-American church experience.

This book is a vital first-step in introducing all Christian Americans to religious thinkers too long ignored by many white American Christians. Yet, it is also a vital call to faithfulness that points out that one can win one struggle, against segregation for example, in a manner that makes further relevance and spiritual power harder in the future.

Reading this book left me, again, angry with what the sin of white supremacy cost the African-American community primarily, but also the rest of us secondarily. The injustice bred all sorts of evils, aborted many goods in the cradle. White supremacy has not gone away and the method to best defeat it remains a primary affiliation to the universal Word of God and His Church. After any short-term victory, the greatest danger is to become captive to the culture, right or left, of the American nation.

I am thankful for this text and urge you to read the book.

—————————————

*As a grad student at the University of Rochester, I became aware of how influential the region was for a time. Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, the birth place of Mormonism, the birthplace of Spiritualism, and the theological decay of the Rochester seminaries (merged into one by the time I was at Rochester) were all highly influential. Sometimes this was for good, often not.

I went to a Bible college in the region housed in the buildings of a forerunner to Syracuse University. We had a plaque to a founding feminist leader and continued the “burned over district” tradition of intense religious experience. While I was there, however, there was a conscience effort to embrace both social action (right to life) and intellectual activity. I had some really outstanding teachers.

**As usual, yesterday’s liberals become the target of today’s liberals. Imagine speaking BOMFOG in the Harvard Divinity School of today! The only words left in BOMFOG would be “of” as in “of” the patriarchy and repression.