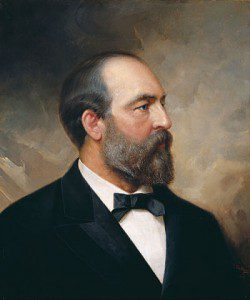

I have been told Americans elect a president and not a pastor. This is true: no president as president baptizes children into the church! Even when we elected a former pastor as president, James Garfield, we did so not so he could preach or administer the Lord’s Supper, but to lead our body politic. Voters liked his background as a Christian minister, yet put him in office for civil service reform!

I have been told Americans elect a president and not a pastor. This is true: no president as president baptizes children into the church! Even when we elected a former pastor as president, James Garfield, we did so not so he could preach or administer the Lord’s Supper, but to lead our body politic. Voters liked his background as a Christian minister, yet put him in office for civil service reform!

I doubt, however, this is very controversial. What these folk seem to mean is that one needs a tough old SOB to get things done and as tough old SOB’s are not saints, they will vote for a SOB that will advance their agenda. This shows a shocking ignorance of saints. Saint Lawrence was put on a griddle and burned for being a Christain and the saint could still crack wise about needing to be turned on the griddle as he was tortured.

Whatever else he was, Saint Lawrence was a tough son of the Church. When one rejects the possibility of a saint as leader, one shoots too low. There is long history of rulers who, mistakes and all, made effective leaders and lived saintly lives.

My favorite such ruler is Kaleb of Aksum, a forerunner to Ethiophia, who managed to defend his nation and do justice. He kept a high civilization going, even helping his Christian neighbors, when much of the rest of the area was chaotic. He was following and improving on a tradition pioneered by Constantine the Great.

My favorite such ruler is Kaleb of Aksum, a forerunner to Ethiophia, who managed to defend his nation and do justice. He kept a high civilization going, even helping his Christian neighbors, when much of the rest of the area was chaotic. He was following and improving on a tradition pioneered by Constantine the Great.

Thousands of Christians prayed for hundreds of years that the persecution would cease and the Roman Emperor would see the light. Constantine did both: literally. Nobody had produced a manual for how to be a Christian and a Roman Emperor so nobody should emulate all Constantine did as he invented the role, but he got the big things right. Saint Constantine saved classical civilization for the future by moving Rome from Rome, a brilliant solution that kept secular (non-Church) education going for another thousand years. Meanwhile, he also favored Christianity as an effective worldview to save the Empire without making Christianity the “official” state religion. This worked and Rome gained a millennium of existence, much of it intellectually and artistically gorgeous. Blessed Constantine was baptized on his death bed: being an emperor meant making “bad” decisions and that was viewed as dangerous to his soul. He was often a SOB, though no Christian defends that part of his record. He is sainted for the good he did, not for the bad.

Later rulers, think King Saint Louis or Good Duke Wenceslaus, did better. The ideal Christian prince did justice to the poor, attacked corruption, defended the weak, and kept the realm safe. Again, such rulers made mistakes, but ruling is fraught with peril. The Russian princes Boris and Glen were canonized for dying rather than resist evil with violence and risk a civil war. There are many historic models, many errors, but a long process over time of knowing what to do if Christian ideas won.

Winning is hard as every revolutionary, suddenly (and sometimes surprisingly) discovers. The saintly ruler has in common failures (he is only human) and an attempt at sanctity. The local Christians did not pick some sympathetic tough guy and elevate him for instrumental reasons. Trying our best we too often got the Blessed Nicholas II of Russia, not a great ruler (!) with deep flaws, but a man who died well opposing greater evil.

Imagine what would happen if we gave up on standards at all!

The fear of the saintly king may be some Victorian idea that “Christianity” enervated a man, making him womanly (!). This was the criticism of macho atheists of the late nineteenth century. As late as my childhood, NFL teams (allegedly) worried about religious football players as they might be “soft.” The stereotype for a Christian ruler might have been a king like Henry VI in Shakespeares series of plays on this sad king of England.

Henry is the son of Henry V, the great victor of Agincourt (also a Christian prince by the way), but one give to monkish living. Shakespeare’s Henry prays a great deal and is soft on his foes. He is easily manipulated by different factions and is just too nice at times to be king.

Or so a superficial reading of the play might lead one to think: religion makes a leader“weak.”*

Instead, Shakespeare plays with such assumptions: the praying Henry survives when other “manly” leaders do not. Shakespeare wrote Henry V after writing the three plays we call Henry VI (I, II, III). Note how he describes the loss of the great Henry V’s empire:

This star of England. Fortune made his sword, By which the world’s best garden he achieved, And of it left his son imperial lord. Henry the Sixth, in infant bands crowned king Of France and England, did this king succeed, Whose state so many had the managing That they lost France and made his England bleed, Which oft our stage hath shown—and, for their sake, In your fair minds let this acceptance take.

Shakespeare blames the “SOB” nobles, not the weakness of Henry VI. Of course, Shakespeare does portray Henry VI as afflicted with mental and physical disorders, but his piety is not the cause, but the iron core that pulls the man through such afflictions. Henry VI is too good for his time: patron of the arts and education. In education alone, he founded schools like Eaton and King’s College Cambridge. Given better nobility, Henry VI could have been great. His nobles saw his weaknesses, and devalued his virtues, and tore the Kingdom apart.

Henry VI endured it all: his very weakness made the SOBs underestimate him, keeping him alive, and his piety kept him building enduring works for England. Shakespeare’s Henry VI is ill served, but lives nearly to the end of the War of the Roses. When he is finally killed, he goes through an apotheosis. His piety did not lose France, his sanctity did not bring on the War of the Roses. Instead, the SOB nobles who thought might was needed for right lost the wars (to Saint Joan of Arc!) and self-destructed.

All Soul’s College, Henry’s work, has given Britain generations of leaders in many fields. Henry was weak physically, but strong in spirit. He persisted and though (the some day) Richard III kills him and Henry VI is given a vision of Richard and England’s doom. Richard has killed his son for “preemption,” Henry, now very strong in God, says:

Hadst thou been killed when first thou didst presume, Thou hadst not lived to kill a son of mine. And thus I prophesy: that many a thousand Which now mistrust no parcel of my fear, And many an old man’s sigh, and many a widow‘s, And many an orphan’s water-standing eye—Men for their sons’, wives for their husbands‘, Orphans for their parents’ timeless death—Shall rue the hour that ever thou wast born. The owl shrieked at thy birth—an evil sign; The night-crow cried, aboding luckless time; Dogs howled, and hideous tempests shook down trees; The raven rooked her on the chimney’s top; And chatt’ring pies in dismal discords sung. Thy mother felt more than a mother’s pain, And yet brought forth less than a mother’s hope—To wit, an indigested and deformed lump, Not like the fruit of such a goodly tree. Teeth hadst thou in thy head when thou wast born, To signify thou cam‘st to bite the world; And if the rest be true which I have heard Thou cam’st—

Shakespeare’s Richard III became a true SOB as ruler as Shakespeare’s Henry foretold. The old King, who would rather have been a commoner, would have died to save England, and hated war, laid down his life with piety. He was a saint and mightier than the SOB. See:

RICHARD I’ll hear no more. Die, prophet, in thy speech, He stabs him For this, amongst the rest, was I ordained. KING HENRY Ay, and for much more slaughter after this. O, God forgive my sins, and pardon thee.

He dies

Maybe a man like that would make a good leader of this republic just now. If not, perhaps it is our vice, fractiousness, and hate that make us unworthy of a saint as leader.

————————————-

*And yes this old secular trope is offensive when it comes to women! The great monarchs Elizabeth I, Victoria, and Elizabeth II show the falsity of a fear of women in power.