“I built that house.”

“I built that house.”

The yellow cottage sat in some bottom land between the hills, valuable land for building and farming. He had been a very young man and had just married the foster-daughter of the owner of that land.

“What happened Papaw?”

He told me the story and it was sad. The story is not mine to tell, but was his: Papaw Earl.

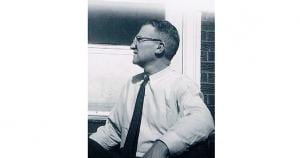

Papaw Earl went for a walk with me and talked to me. Both my Papaws were great men, I did not know what a blessing this was. Weren’t all grandfathers wise and good? As we just passed his birthday, I have been thinking about talking to Papaw.

He was not quick to speak and slower to speak about himself. He played checkers with me for hours and I won . . .rarely. The goal was to keep playing, hope he got distracted, and so win! I kept count and (as I recall) thirteen games would just about do it. The point of checkers, like baseball, is to provide an excuse to talk.

You move. You think, a bit. You speak, but not too much since Papaw (or any opponent) must be given his space to move and to think. The conversation unwinds. A good story, for example, must be told many times, so that the nuances, the humor or the sorrow, seeps into the listener. Eventually (so my dad reports), you can tell the story better than the original story teller and the anecdote has passed into lore.

I would hear from Papaw Earl, over the years, of a life that was a bit Prince Hal to Henry V: roistering young man transformed by the good God to elder in his church. That made for a good balance of stories for him to tell: a young man who found Jesus so returned a chicken he had liberated to the owners. A glib and handsome man who could shill for patent medicine barkers (“I will take one, sir.”) and so sell product. He quit all that. . .just as he mostly did not drink alcohol. He did not mind if you did and once he took a sip of champagne and commented (truthfully I am sure): “I made better stuff than this.”

So it went over the years . . .

He told me once, this man who did not lie, that if I went to a grave yard and asked, “What are you doing down there?”, the response would be “Nothing at all.” Or had he said . . .nothing at all. He said “nothing at all” in a spooky voice, so I inserted the quotation marks. Yet this was false, I tried. Nobody said anything. What could this mean? I would hate to say how long it too me to realize the clever equivocation that made the joke work. Papaw was telling the truth-nothing at all was said.

A good conversation takes a long time to be born. I was there, waiting, listening, moving a checker, walking. The stories would come, questions were asked and I learned so much. These were seminars in being human, and in my particular case, in being a man. If (as a young man) I disastrously failed to live up to the code, at least I had been given a pathway home.

Over Thanksgiving, I visited my brother’s house where on the wall he has placed pictures from our family history. Dad and Mom live there with him and we looked at those pictures. One was of the very day Papaw told me about his house and so much family history came together. I was glad for the blurry Kodachrome.

Over Thanksgiving, I visited my brother’s house where on the wall he has placed pictures from our family history. Dad and Mom live there with him and we looked at those pictures. One was of the very day Papaw told me about his house and so much family history came together. I was glad for the blurry Kodachrome.

And Papaw Early is not just captured in a picture, or my fading memory, he is very much alive waiting with Nana, as is Papaw Shelby and Granny, and so many absent friends.

Hell, after all, may be for those bored with the Logos, the dialectic, the conversation, lore.

Dad, my son named after Dad, my brilliant son-in-law, a good friend, and my brother rehearsed family lore, talked some politics, smoked a cigar, drank a wee bit of the True. We rehearsed family lore.

By the good God, may we do the same this Christmas. May we take the time to talk: a foretaste of the New Jerusalem. There are so many waiting on us, including Papaw Earl.

I am sure he will beat me at checkers on that glorious day.