If you wish to keep thinking systems cannot be unjust, do not read Dickens. If you must continue assuming decent people cannot be ground down by poverty and become overwhelmed by vice, stream the musical and do not read Oliver Twist.

If you wish to keep thinking systems cannot be unjust, do not read Dickens. If you must continue assuming decent people cannot be ground down by poverty and become overwhelmed by vice, stream the musical and do not read Oliver Twist.

Wait!

Do not, under any circumstances, watch the musical before reading Oliver Twist.

This is not due to spoilers, Dickens can handle those and still keep our attention, but due to how badly the musical gets the book. The book is older than the musical, but the novel is less dated. While the musical is full of sappy early sixties sentimentality, the novel is sentimental without being foolish. In the musical, all the prostitutes have hearts o’gold and brutal thieves are more lovable than the good folk, as if grinding poverty and a lack of justice can be defeated if one just smiles and does a dance. Dickens shows the humanity and the brutality of unjust cultural systems, but he does not excuse bad individual behavior either. The kind, Christian people in the novel are mostly written out of the musical.

The musical makes poverty and slums seem like a good idea. The novel, on the other hand, is harder, while holding out hope. Good people are generally better to know than bad people. Some folk who seem good are hypocrites. That is real life: most Baptist ministers are people who love and help people, but are imperfect. A few Baptist ministers are bad and some are very bad.

Dickens was the rare writer who could negotiate the perils of morality: he knew no man was so bad that he did not have redeeming qualities and no man so righteous that he lacked foibles. He wrote both into his characters, but also told the truth: it is generally good to be good. His characters that are bad are harmful in so far as they are bad, but good where the image of God creeps into their lives and offers the possibility of redemption.

Oliver Twist condemns the hypocrisy of Christian England for falling short of her dreams of a green and pleasant land, but does so without undercutting the vision. Dickens wants England to live up to her Christianity, not get rid of the Faith. He knows England is good only so far as it is Christian and Christian only so far as she is good.

Oliver Twist is a fast novel by later Dickens’ standards and left me with these questions:

First, the church does great charitable works in Dickens’ England, but those works often go awry and fall into the wrong hands. How can the Church prevent her charity from becoming the opportunity for the Bumbles of this life?

Second, Rose, Agnes, and Nancy present three very different outcomes. Only Rose is true to Christian morality and this safe way preserves her. Agnes falls short and then the Church falls short in response. Nancy chooses poorly right to the end, partly motivated by a perverse love for Bill. What do Agnes and Nancy have in common? How does Rose rise above the hypocrisy of the “establishment’ without rejecting Christian morality?

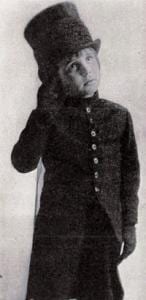

Third, the character of the Artful Dodger is one of the best examples of the “lovable rogue.” You cannot condone his lifestyle, but his good humor makes it seem harmless. Some of Dickens contemporaries did not like this type of portrayal as they felt it glorified vice. Of course, no careful reader would wish to be the Dodger, but this role in the stage play, changed and made even more palatable, seems to provide some evidence for the concern. Dickens saw that people doing bad things might have good qualities, while the musical suggests good qualities make the lifestyle not so bad. But after all, some the Dodger robbed must have felt the loss and been harmed by it. The “profits” only allowed the Dodger and others like him to grow up to be like Bill.

How can we avoid glorifying the “lovable rogue” while still telling the truth about the criminal world?

Fourth, any character who is a reader of books in Dickens novels, including this one, are good natured, but a bit useless in the real world. What was Dickens saying about the class that was making him rich?

Fifth, Oliver is born into a “higher class.” Does Dickens allow “blood” to out in this book? Why is Oliver “different” from so many of the other boys? How much does family heritage play in how a person develops?

Oliver Twist is a warm up in some ways for the more intense David Copperfield, but it tells a child’s story better than that book. Dickens was writing what he knew and the passion tells. His ability to make middle class England care about “bad girls” like Nancy and wish good for them was the start of a Christian response to a broken culture. This novel was one tiny contribution to the emancipation of women. This is a great summer read in troubled times.