It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a human in possession of a good education must also wish to continue learning. Sadly, like other universally acknowledged truths we wish were true, it isn’t really. Despite the desires of Mrs. Bennet, not all men with a large fortune want a wife and regardless of what we say, many of us do not want to keep learning.

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a human in possession of a good education must also wish to continue learning. Sadly, like other universally acknowledged truths we wish were true, it isn’t really. Despite the desires of Mrs. Bennet, not all men with a large fortune want a wife and regardless of what we say, many of us do not want to keep learning.

I am told that gyms stay in business by selling memberships that people do not use, but also do not cancel, because they want to work out. Cancelling would be admitting that the workout is not going to happen as we know it should. How many people buy a second language program, keep Second Language I on the phone, yet never get to Second Langage II?

Some Reasons to Keep Reading

So it is with lifelong learning. We pretend to ourselves that life will naturally teach us what we need to know and that formal education was a phase to get us ready to receive those lessons. This is undoubtably true for certain kinds of practical wisdom, if we received a good foundational education. It is not true about our thinking skills. There is, so far as we can tell, no way to learn some things without articles or books. If a person has a highly skilled job, then the job will keep pushing him or her forward in that area.

Sadly, I meet people who cannot read their college papers in humanities. Surely none of us think that we should do our most sophisticated thinking (ever) about human things, say politics, love, or relationships (to pick three topics) in our early twenties? We can memorize facts or even adopt a decent view of reality in college, but then we must keep growing. Thank God I am not the person I was in my college years and part of that has come from reading and thinking about serious books.

Someone might suggest that my job requires this continued reading. That is true. Just as the person who works in a gym has a head start on lifelong learning, so a professor or teacher has it easier in this task. Maybe. However, just like anyone else we can specialize and become mature in our subject matter, but regress in other important areas. For example, my job teaching philosophy did not necessitate reading Jane Austen, but Jane Austen has given me (thank God) a better view of womankind than one I used to have. The Bronte sisters helped as well.

Once I started teaching great texts, I had to go out of my way to read works that were contemporary or dealt with issues that my job was not covering. How can I vote thoughtfully if I will not take the time to try to understand China, First Nations, or other areas. Of course, nobody can learn about everything and so a republic requires a community. My friends fill me in where my knowledge is (and probably will remain) inadequate. Bob controls my thinking on Iran! Father Richard has helped me on Syria. Lindsey gives me readings on First Nations.

We must keep reading if we can.

Try Reading This Insanely Important Dull Book

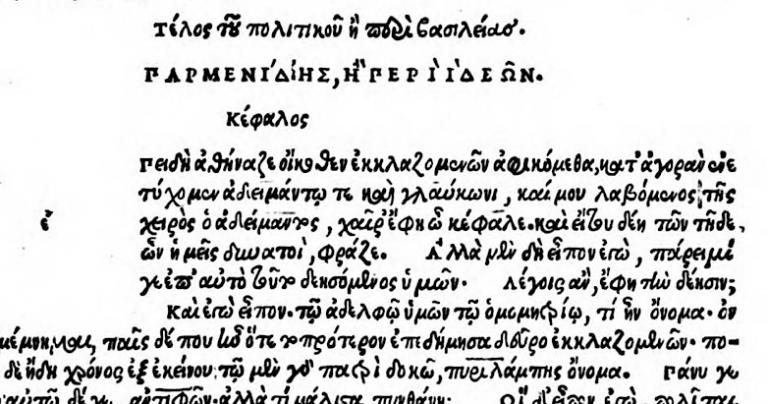

I saw this as I worked hard on Parmenides, a dialog that people who enjoy reading novels (as I do) will rarely choose for fun. I will admit that I started re-reading the Platonic dialog for work, but then kept going so to stretch certain mental muscles that do not get used enough.

Please read the end of the dialog carefully. Think. Try unpacking it. Parmenides, a great thinker, is teaching young Aristotle (not that one!) and young Socrates (yes, that one!) about how to do argumentation. The dialog has a careful scene setting, but then spends pages piling on the careful distinctions, arguments, and counter-arguments.

What you are about to read has no seeming practical value. Parmenides and Aristotle are discussing whether the idea “one” exists. (Wait, gentle reader! Do not go away! Stay for a minute! There will be a point if you stay with the argument . . . ) Read Parmenides:

Then if we were to say, to sum up, ‘if one is not, nothing is,’ wouldn’t we speak correctly?”—“ Absolutely.” “Let us then say this –and also that, as it seems, whether one is or is not, it and the others both are and are not, and both appear and do not appear all things in all ways, both in relation to themselves and in relation to each other.”—“ Very true.”

Plato knows how to write an interesting bit of dialog (see Republic), but this is not interesting dialog. Parmenides thinks he has proven that if “one is not” then nothing is. That’s absurd, of course, so you might think that the idea of “one” must exist. Yet he has also shown that if the idea “one” exists, then nothing is. This cannot be right.

When we get to the end of this long demonstration of an argument, we wait for the lesson. What is young Socrates to learn? What are we to learn? The dialog has a careful setup, spends pages making us think, reading slowly to follow what is being said, but then nothing. That is the end. Full stop.

What?

This cannot be right. When I got to this point, I was frustrated. What is the solution? I began sketching out ideas and then I saw that the master teacher, Plato, had won. He had set me up to think with a puzzle. He gave no solution.

Oddly, the very process is good for my mind. I could feel the good tired of thinking hard and certain issues that I might have thought difficult last week were easier. My thinking was on a higher plane (at least for a moment)! This is, of course, to live a human life. Is that practical? What does it mean if we say being more human is impractical?

Plato knows that we aspire to life long learning, but that as we get older (ahem!) we become like Parmenides when he is challenged to think:

In the end Parmenides said: “I am obliged to go along with you. And yet I feel like the horse in the poem of Ibycus. Ibycus compares himself to a horse –a champion but no longer young, on the point of drawing a chariot in a race and trembling at what experience tells him is about to happen –and says that he himself, old man that he is, is being forced against his will to compete in Love’s game. I too, when I think back, feel a good deal of anxiety as to how at my age I am to make my way across such a vast and formidable sea of words. Even so, I’ll do it, since it is right for me to oblige you; and besides, we are, as Zeno says, by ourselves.

And so it goes.

Be Like Dad

My eighty year old dad is a good model to me. He keeps learning, arguing, changing. He challenges me all the time. So too, I cannot just “have my opinions” or live on what I once knew. I must keep thinking and that means reading books that do not end with easy answers.

And after all, isn’t that many of the books of the Bible? Read Ecclesiastes. Think about Judges. No easy answers there, but a call to think. What do we do in the face of vanity? What if all is vanity really? What happens to a culture when everyone does what is right in his own eyes? Socrates, as well as Parmenides, really loved learning; and they were both ever sensible of the warmest gratitude towards the persons who, by bringing them into a hard discussion, had been the means of educating them.