By Dr. John Wind

The “social gospel” has been a powerful yet controversial force within Christian history, particularly within American Protestantism. Emerging in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this movement sought to intertwine social reform with the Christian mission, emphasizing the importance of societal transformation alongside personal conversion. However, the historical impact of the social gospel on American Protestant missions in China reveals significant dangers that remain relevant today, particularly as the church continues to engage with social justice issues.

The social gospel movement began as a response to the rapid social changes brought about by industrialization, urbanization and immigration in the United States. Christian leaders like Washington Gladden and Walter Rauschenbusch believed that the church had a responsibility not only to save souls but also to address social ills such as poverty, inequality and injustice. They argued that Christianity should play a role in reforming society, advocating for labor rights, education and improved living conditions.

However, the movement quickly became a theological battleground. Early proponents of the social gospel often held a high view of Scripture and saw social action as a natural outgrowth of Christian discipleship. Yet, as the movement evolved, it began to adopt more liberal theological positions, influenced by the rise of German Higher Criticism, Darwinian evolution and Freudian psychology. These influences led to a reinterpretation of Christian doctrine that de-emphasized the necessity of personal conversion and the authority of Scripture, focusing instead on social ethics and community transformation.

The Social Gospel’s Impact on Missions in China

This theological shift had profound implications for American Protestant missions abroad, particularly in China. At the turn of the 20th century, China was a land ripe for evangelistic efforts. The fall of the Qing Dynasty and the rise of the Republic of China created a window of opportunity for missionaries to spread the gospel in a nation undergoing significant social and political change.

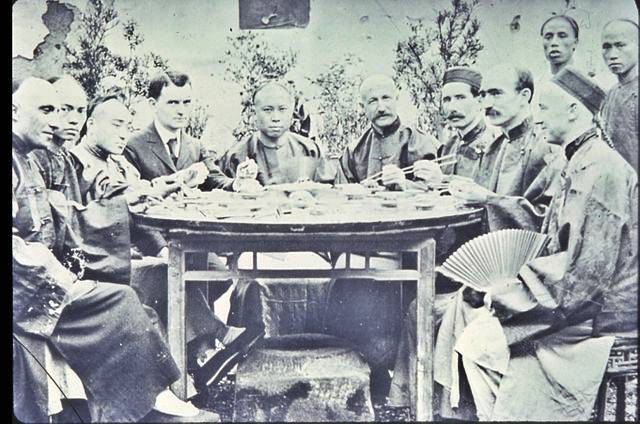

American missionaries arrived in China with a dual purpose: to preach the gospel and to “civilize” the Chinese people by introducing Western education, technology and democratic values. This blend of spiritual and social missions reflected the broader influence of the social gospel, which viewed societal transformation as integral to the Christian mission.

Initially, this approach seemed successful. Missionaries found a receptive audience among Chinese students and intellectuals, many of whom were eager to embrace Western knowledge and ideas. The early social gospel, with its emphasis on both individual conversion and societal reform, created a sense of unity among missionaries of various denominations and theological backgrounds.

However, this unity was built on a fragile foundation. Beneath the surface, significant theological differences existed between conservative and liberal missionaries. Conservatives emphasized the primacy of evangelism and the necessity of personal conversion, holding to a high view of Scripture and traditional Christian doctrines. Liberals, on the other hand, were more inclined to reinterpret Christian teachings in light of modern science and philosophy, prioritizing social reform over evangelism.

As the social gospel gained traction, particularly after World War I, these theological divisions became increasingly apparent. The war shattered the optimistic belief in the superiority of Western civilization and Christian culture, leading many liberal missionaries to question the exclusivity of the Christian message. Influenced by the growing tide of cultural relativism and religious pluralism, they began to advocate for a more inclusive approach that sought common ground with other religions, particularly Confucianism and Buddhism.

This shift had significant implications for missions in China. The once-strong emphasis on evangelism began to wane as missionaries focused more on social reform and interreligious dialogue. This was particularly evident in organizations like the YMCA, which played a leading role in promoting social service and community development in China. The YMCA’s approach evolved from a balance of evangelism and social service to a focus on social reform and cultural accommodation, reflecting the broader influence of the social gospel.

The impact of the social gospel on American Protestant missions in China was profound, yet ultimately detrimental to the long-term success of these missions. By the 1920s and 1930s, the social gospel had led to a significant shift away from traditional evangelism. The focus on social action and cultural accommodation led many missionaries to downplay the exclusivity of the Christian message, instead presenting Christianity as one among many paths to moral and social improvement.

This approach failed to resonate with the broader Chinese population, who were increasingly drawn to secular ideologies like nationalism and communism. The social gospel’s emphasis on social reform, divorced from the proclamation of the gospel, left a void that these ideologies quickly filled. As Chinese society became more politically and ideologically polarized, the influence of Christianity waned, and many missionaries found themselves marginalized or expelled from the country altogether.

The culmination of this shift was the 1932 “Rethinking Missions” report, produced by an interdenominational committee, which called for a reorientation of missions away from evangelism and toward social service and interreligious dialogue. This report marked the final break between evangelical and liberal missionaries, solidifying the association of the social gospel with theological liberalism and further alienating conservative evangelicals.

Lessons for the Church Today

The history of the social gospel in China offers important lessons for the church today, particularly as it navigates the complexities of engaging with social justice issues. While the church has a clear biblical mandate to care for the poor, fight injustice and promote peace, these efforts must not come at the expense of the core message of the gospel: the salvation of sinners through faith in Jesus Christ.

One of the key dangers of the social gospel, both in the past and today, is its tendency to prioritize social reform over personal conversion. When the church becomes primarily focused on societal change, it risks losing its distinctiveness as the bearer of the gospel message. Social action, while important, must always be secondary to the proclamation of the gospel. The church’s primary mission is to make disciples of all nations, teaching them to obey everything Christ has commanded (Matthew 28:19-20). This mission cannot be fulfilled if the gospel is reduced to a set of moral principles or social programs.

Moreover, the social gospel’s tendency to accommodate the gospel message to the prevailing cultural and ideological trends is another significant danger. In China, this accommodation led to the dilution of Christian doctrine and the eventual rejection of Christianity by many who saw it as just another form of Western imperialism. Today, the church faces similar pressures to conform to cultural norms and political ideologies, whether in the form of secular progressivism or religious pluralism. The church must resist these pressures and maintain its commitment to the authority of Scripture and the exclusivity of the gospel.

The legacy of the social gospel in Chinese missions serves as a stark warning for the church today. While the pursuit of justice is a vital expression of Christian faith, it must never eclipse the church’s primary mission of proclaiming the gospel. The history of American Protestant missions in China demonstrates the dangers of allowing social reform to overshadow evangelism, leading to the erosion of theological clarity and the weakening of the church’s witness.

As the church engages with the world, it must do so with a clear understanding of its mission and message. Social action is an important aspect of Christian discipleship, but it must always be grounded in and directed by the gospel. The church’s ultimate goal is not merely to reform society but to bring people into a saving relationship with Jesus Christ. This is the message that has the power to truly transform lives and societies, both in China and around the world.