At the end of It’s A Wonderful Life, Christmas is celebrated; Clarence gets his wings; the Building and Loan books are rectified; the community turns out en masse to support their dear friend as he has always supported them; and George learns to appreciate the meaningful life he is living and the many blessings that are his.

George Bailey, Continued

What do you suppose happens to the Bailey family next, after the camera cuts away?

If we were to follow this fictional family through the years after the film concludes, do you think that we would witness George’s consistent and persistent contentment? Or would his spiritual epiphany be temporarily belied—though not forgotten—during each new crisis at the Building and Loan, family illness, and home repair? Would George ever again ask his wife, more in rhetorical frustration than in genuine inquiry, things like: “Why do we have to stay around this crummy little town? And why do we have to have all these kids?”

If I had to guess, I would wager that the exercise with Clarence and the subsequent embrace of his community permanently ensure that George never again despairs, or wavers on the foregone conclusion of whether his life is worthwhile.

But I would also bet the mortgage that George—who is around forty years old when the movie concludes—has plenty of discontentment, frustration, and anger still ahead.

That is because discontentment, frustration, and anger were always more about George—the flip sides of his uncommon drive, ambition, and energy—than about Bedford Falls per se. After all, George’s life was never so bad: roof overhead, steady job, loving wife, good friends, food on the table. A lot of less fortunate people would have been happy to trade places with him, even without the benefit of Clarence’s visit.

But George is a visionary, and discontentment is the inescapable byproduct of his vision. He is inclined to create for himself the world that he wants to see, not to make the best of his world as it is.

So, George is a poignant and instructive hero not just because of his deeply rooted service to others, but because of the ways that he sacrifices himself and his own desires in order to serve. We all understand that his extraordinary talents and ambition—his very capacity and desire to be and do something other than what he is called to be and do—are inextricable from the heroism of his surrender to an ordinary life.

When a man makes the kind of sacrifices that George makes—when he answers the call to pursue what is wonderful rather than what is happy—we rightly recognize his virtue. Moreover, we assume as a matter of course that his feelings are less important than his virtue. That is, we endorse the idea that if doing the right thing makes him unhappy, he should do the right thing anyway, because he is called to something higher than his own happiness.

Can Women Follow George Bailey’s Example, Too?

But would we regard a discontented yet other-serving female character with the same respect and deference that we show George Bailey?

I’m afraid not.

Unfortunately, modern feminism’s emphasis on personal choice (unto parody—recall the Sex and the City scene where Charlotte screams over and over, “I choose my choice!”) has rendered us incapable of judging a woman’s decisions by any rubric more meaningful than how ostensibly happy they make her.

When I was 24, I left a doctoral program in English literature because I had no interest in wrenching my life to go on a fast-shrinking job market. I wanted to get married to my then-law-student boyfriend, settle down in my native Philadelphia, and start a family. I got married when I was 25, and had my first baby at 27. Over the next six years, I had two more babies; left a full-time job to shoulder the increasing responsibilities of primary caregiving for three children; and began to fit a fledgling writing career around my husband’s primary breadwinning schedule and my children’s needs.

The Feminism Problem

I am a practicing Catholic, yes; but I am also of the secular East Coast and the elite academy. Thus, at each of the aforementioned inflection points, some of the well-wishes I received bespoke puzzlement. Underneath some of the spoken questions (“Wow, what will you do with yourself?”) were the unspoken ones (But I always thought you were smart? Driven? Ambitious? All to take a back seat to your man’s career?) I was not offended; I understand that the post-1960’s hegemony of feminist talking points means that some women who put their careers first (among those who are sufficiently privileged to have any choice in the matter) find it difficult to accept that those of us who put children first really do know our own minds.

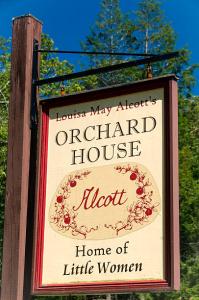

I also was not surprised. It was ironic, but fitting, that my academic work in graduate school had often focused on Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1868). This story of four girls coming of age just outside Boston during the Civil War features Alcott’s semi-autobiographical self, Jo March, as its protagonist. Much like George Bailey, Jo is a visionary. She has personal ambitions that should take her far from home, and is constantly discontented with how her own family and the wider world fail to live up to her expectations. Her hot temper is difficult for her to control. She wants to write great books, and she does not want to marry. By the end of the novel, she has all but given up writing, after coming to the hard-won self-knowledge that she has “talent,” but not “genius.” She is also married, with two children. And she is, finally, at peace, secure in the knowledge that she is living as she is called to live. True peace is harder to come by than mere happiness.

Yet, the feminist scholars that have considered Little Women have been uniformly disappointed at Jo’s end in the novel. That she is fulfilled and productive is not enough; they wanted to see this literary heroine fulfill the specific dreams that she crafted for herself at fifteen—first and foremost, to remain unmarried—not to adjust those dreams to meet changing circumstances and demands. They judged her ultimate (lack of) success by the measure of how she conceptualized happiness when she was a teenager. In short, they could not abide a woman growing up, and making the kinds of compromises that adults—both male and female—often find it optimal to make.

The Maternalism Problem

At each of the inflection points in my own life and career that have brought me further from the accepted playbook of highly educated twenty-first century feminism, there have also been well-wishes that bespoke triumph: another woman who recognizes her true maternal purpose! These well-wishes have been those of the “oh, the kids need that time from a mother” and “you’ll never regret spending more time with your children” and “isn’t every moment with a baby just a breath of heaven?” variety.

I was not offended by these comments either. After all, the specter of someone like Mary Bailey—the Norman Rockwell painting of well-coiffed feminine contentment who smiles irrepressibly while papering over holes in a dilapidated house, tending multiple babies, and steadying a less than easy-going husband—hangs over all women, and especially all mothers.

But I am not particularly well-suited to baby-care by nature. Yes, my love for my children knows no bounds, nor does my energy, affection, and diligence in caring for them. And no, I would not trade this precious time with them for anything (which is obvious, since if I wanted to trade it for anything, I would have done so). Still, I taught at the collegiate level for a reason. I am a teacher, not a nurturer; and a coach, not a cheerleader. That doesn’t make me less of a mother, but it does make me less amenable to the kind of maternalism that is often presumed to go along with the choices I’ve made (largely because it features prominently in the self-conception of many other women who have made similar choices).

Women Can be Ordinary Heroes, Too

So, upon being confronted with well-meaning well-wishes of either the feminist or the maternalist type, would I be likely to express the kind of frustration with my own choices that George Bailey expresses with his throughout most of It’s a Wonderful Life? Would I be likely to complain about how few hours there are in a day and how many more of them I wish I could use to work; or about how enervating it is to never find time to fold the clothes and how frustrated I often am digging through the clean baskets; or about how I would sometimes be much happier in the minute-by-minute sense if I were spending three long days on a college campus each week, as I did when my older children were babies?

Of course not.

Because, if I did, people would neither say nor think, “Good for you, lady, doing what you know is best regardless of how it feels in a given moment.”

No, some would think, “poor thing, victim of the patriarchy” (and, in not so many words, say it, too). And others would think, “well, I guess she isn’t really meant to be a mother” or “this must be what those ivy league schools put in girls’ heads” while offering fervent prayers for my reform.

Fortunately, I’ve seen It’s a Wonderful Life; and I recognize George Bailey as a hero. More importantly, I’ve read Little Women; and everyone that has had the misfortune to converse with me on these topics over the past decade recognizes Alcott’s Jo March as my hero.

So, I know that moment-by-moment happiness isn’t actually the point for women any more than it is for men.

After all, women are grown ups. We actually can “choose our choices.” And we should be unabashed in claiming for ourselves the respect for having weighed those choices not by how they make us feel today, but by how they optimize our long-term ability to give unto the various others (people, places, etc) that God plants in our lives.