To his audience, and to us, Jeremiah says:

seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile, and pray to the Lord on its behalf, for in its welfare you will find your welfare (Jeremiah 29:7, ESV).

The Church is on sojourn in this world. We are here temporarily. Thus, we hold things lightly, be they projects of liberation, social justice, conservation, revolution, or nationhood. Yet, this exilic posture orientates us towards the things of this world so that we can be in, but not of the world.

This orientation is not passive. Seeking the welfare of the city (polis) in which we live is a political activity. Yet, what does it mean to seek the good? Is it goodness according to our understanding? Is it goodness as our neighbors understand it? Or are we to bring the Good as it is in heaven down to earth, as if that is our calling as Christ’s disciples?

As we find in the teachings of Jesus, seeking the welfare of our city has to do fundamentally with peacemaking. To His followers, Christ says:

Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God (Matthew 5:9).

What does this entail for our current situation? Especially for those of us who find ourselves in intensely polarized societies? In a society in which the good is fiercely contested, how can we seek the city’s welfare and peace?

Polarization, the increasing ideological and affective (or felt) difference between the American Left and Right, is alarming for many Americans. It is understandably alarming. But the alarm seems to stem from a mistaken conception of politics.

Recovering Agonistic Politics

One of the most formative philosophers in my political thought, Chantal Mouffe, argues that many Western thinkers gravely misconstrue politics. For instance, for American political philosopher John Rawls, politics is simply a difference of moral interests. [1] As the eventual Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt wrote,

Liberal concepts typically move between ethics and economics. From that polarity they attempt to annihilate the political as a domain of conquering power and repression. [2]

Mouffe appropriates Schmitt, which is interesting since Mouffe is squarely on the political Left. Mouffe redeploys Schmitt’s definition of politics as predicated on the friend/enemy distinction, rather than the typical liberal understanding of politics as “a plurality of interests” not having to do with “conflict, power and interest.” [3]

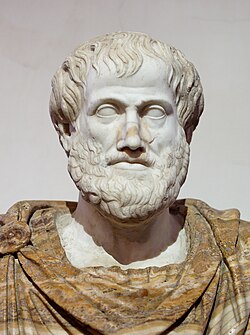

As Mouffe rightly points out, “In politics the public interest is always a matter of debate and a final agreement can never be reached; to imagine such a situation is to dream of a society without politics.” [4] This understanding of politics deeply resonates with classical political philosophy. In his Nichomachean Ethics, Aristotle writes, “If citizens be friends, they have no need of justice.” That is, if people already get along, there is no need for navigating their disagreements.

Thus, as Mouffe puts so well:

Once we accept the necessity of the political and the impossibility of a world without antagonism, what needs to be envisaged is how it is possible under those conditions to create or maintain a pluralistic democratic order. Such an order is based on a distinction between ‘enemy’ and ‘adversary’. It requires that, within the context of the political community, the opponent should be considered not as an enemy to be destroyed, but as an adversary whose existence is legitimate and must be tolerated. We will fight against his ideas but we will not question his right to defend them. [5]

The only “enemy” is the one who does not follow the democratically agreed-upon rules binding the body politic together. But within the body politic, politics will always be “agonistic.” [6]

Reframing Polarization

Theologically, the wild and unpredictable mix of fleshliness, time, and sin necessitates the art of politics to hold human societies together. Polarization is a part of sinful life.

Once we recognize the agonistic nature of politics, we can start to see polarization and political division not as an exception to politics. Rather, it is a consequence of it. There are factors, be they policy, political culture, etc., that condition and shape polarization as we see it today.

On the one hand, we can never make politics completely peaceful. Or, as Aristotle puts it, we can never create a society of true friends. On the other hand, we can tame the excesses of the conditions creating polarization. Thus, we must tackle whatever the root causes are of polarization if we are to seek the good of our cities and nation.

The Root Causes of Polarization

We have already touched on some of the research on polarization in a prior article. As we walk through some of the root causes of polarization, let us think about what potential remedies we can offer.

1. Social Sorting

One main cause of polarization is what social scientists call “social sorting.” Essentially, this means that people sort themselves into specific groups. Polarization arises when people sort themselves into political groups that they identify with. But this sorting is about more than just ideology. As Lilliana Mason has found, those within the American Left and within the Right are becoming more alike in how they dress, shop, and consume. As she puts succinctly, “as Republicans and Democrats grow more socially distinct, they like outgroups less and privilege victory over the national greater good.”

Another researcher, Petter Törnberg (whose work we have already discussed here) comes to a similar conclusion regarding the internet. As he writes,

digital media can intensify affective polarization by contributing to a runaway process in which more and more issues become drawn into a single growing social and cultural divide, in turn driving a breakdown of social cohesion.

What Törnberg is saying is that digital media only intensifies social sorting, casting all of life into a Manichaean battle over good versus evil.

2. Primed Exposure

Most people assume that echo chambers cause polarization. This language implies a loss of connection and discourse between political groups. But as Törnberg finds, it is not isolation that drives affective polarization. It is exposure.

Clashes with opposing groups become Kierkegaardian moments of decision. When confronted with an outsider perspective on any hot-button social issue, Americans feel they must pick a side. Unsurprisingly, they will choose the side which their side already has laid out for them.

Additional Causes

Partisan media comes to mind as a driving factor behind polarization. This is true with a qualification. Biased media outlets do have a polarizing effect. But this effect is restricted towards increasing the polarization of those who are already most polarized.

Existing research is unclear on whether access to internet drives polarization. However, one’s social circle can amplify the effects of partisan media. There is also literature showing that merely being exposed to coverage about polarization increases polarization.

Other clear causes include political campaigns and major political events such as elections, which has been shown to increase polarization significantly.

Peacemaking

Let us now turn to an action plan. Our vocation to be peacemakers requires knowing something about the cities we find ourselves in. Once we know these things, we can faithfully respond to the peacemaking vocation.

1. Revitalizing the Republic

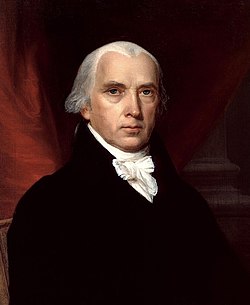

Social sorting leads to what James Madison in Federalist No. 10 calls “faction.” Faction entails putting the good and interests of one’s group over the good and interests of the whole community. As Madison writes, “The latent causes of faction are thus sown in the nature of man.” Faction cannot be prevented, since it is a natural part of human life.

Madison felt that though faction cannot be prevented, it can be mitigated. And since faction results from human nature, mitigation must be structural rather than interpersonal. Madison felt that the American republic, wherein representatives are elected by constituents, could prevent the national spread of faction. Yet, we now live in a nation riddled by faction.

On the structural level, we Christians must ensure that politicians are accountable to their constituents. Money drives politics, both through lobbying and through general political inequality (whereby wealthier citizens have more say than poorer citizens). This does not match the founders’ vision of the American republic, and is more akin to an oligopoly, wherein corporations and wealthy donors drive politicians’ actions and decisions. A revival of the American republic, in which representatives represent their constituents instead of donors, might curtail faction once again.

2. Promoting Social Cohesion

Simultaneously, we must take Paul’s injunction seriously: “If possible, so far as it depends on you, live peaceably with all” (Romans 12:18). This includes spreading the ethic of living peaceably within our civic neighbors.

While we cannot produce perfect social harmony (or Aristotelian true friendship), we can promote social cohesion. Despite irreducible difference and disagreement, we can share the liberal virtue of civility and the Christian virtues of hospitality, love, grace, and peace. This is not in pursuit of some conflict-free politics, which is not politics at all. Rather, it is to produce the sort of agonistic pluralism that Mouffe writes of. This pluralism is one in which differing factions maintain some degree of antagonism towards opponents. Yet, they will see their opponents as adversaries, not enemies.

Concretely, this looks like resisting the forces of social sorting which are pushing Americans into two all-encompassing camps. We must ensure that our social networks remain diverse in terms of race, class, ideology, lifestyle, consumption, culture, and religion. American polarization intends to over-identify us with one of two options. We must shore up our dignity, as well as that of our neighbors, insisting that we are irreducible to the slew of preferences that the two-party system has on offer.

3. Calling Towards a Higher Identity

As Lilliana Mason writes in Uncivil Agreement,

The competition is no longer between only Democrats and Republicans. A single vote can now indicate a person’s partisan preference as well as his or her religion, race, ethnicity, gender, neighborhood, and favorite grocery store. This is no longer a single social identity. Partisanship can now be thought of as a mega-identity, with all the psychological and behavioral magnifications that implies. [7]

The Gospel provides humanity instead with a higher decision. Will we belong to the God who made us for Himself? Or will we choose to define ourselves? As Madison wrote, faction is the fruit of human nature. Cast theologically, polarization is the result of humans creating a system which magnifies our faults and then identifies us.

As Christians, we must resist this identification, for we are citizens of the Kingdom before we are citizens of this world. And as witnesses to what Christ has done for us, we are also tasked with bringing the good news to our neighbors that there is a God who defines us, and our true identity in Christ the Redeemer is worth infinitely more than any worldly system can offer.

Notes

1. Chantal Mouffe, The Return of the Political (New York: Verso, 1993), 49.

2. Quoted in Mouffe, The Return of the Political, 49.

3. Mouffe, The Return of the Political, 49.

4. Mouffe, The Return of the Political, 50.

5. Mouffe, The Return of the Political, 4.

6. Mouffe, The Return of the Political, 6.

7. Lilliana Mason, Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2018), 14.