In recent weeks there seems to have been a significant uptick in online discussion and exploration of the place of women in LDS theology and their relationship to priesthood. Joanna Brooks has been holding an insightful study session on what priesthood has meant at varying periods of the Church’s history, suggesting that the concept has been far more ambiguous and malleable than generally thought, while a number of blogs and other forms of media have given prominence to issues that bear directly or indirectly on the status and role of women in the Church, such as the visibility of Heavenly Mother in orthodox belief and practice.

One aspect of the discussion about the place of women in LDS theology and ecclesiology that has yet to be fully explored is the question of how Mormon thinking about females and their relationship to divinity and priestly power is a function of the broader context of Christianity’s development in Western religious history. Although it is generally recognized that both early Mormon and late 20th century LDS articulations of femaleness as well as the relationship between gender and the priesthood are intricately connected to the social and religious conventions of the eras in which they developed (both in how they reinscribed and sometimes departed from traditional norms), significantly less attention has been given to the larger questions of why women have been virtually shut out of priesthood and cultic functions in Christianity more generally for the last two millennia and why God has been imagined primarily in male/masculine terms.

What historical factors led to this peculiar state of affairs? And to what degree can we be confident that Mormonism’s own views about a male-only priesthood and a male-only godhead are not a product of the same historical contingencies that influenced the development of Western Christianity?

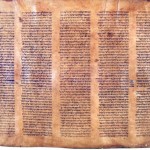

Fortunately, April DeConick, a scholar of early Christianity at Rice University, has tackled the first of these questions in a provocative recent publication titled Holy Misogyny: Why the Sex and Gender Conflicts in the Early Church Still Matter, in which she traces the roots behind traditional Christianity’s penchant for devaluing the female. DeConick brings to her study a wealth of background knowledge, which she skillfully deploys in a survey covering more than a millennium of Israelite, Jewish, and Christian history and a broad swathe of the Mediterranean cultural context in which Christianity took shape and became institutionalized. Through a careful examination of a wide variety of canonical and extra-canonical texts, she shows how the divine and human female was systematically downgraded and erased from Christian tradition–a development that has had lasting repercussions on subsequent human history.

DeConick begins with a reconstruction of early Christianity that suggests a devaluation of the female was not inevitable or inherent to the theological perspectives of the movement’s earliest figures and adherents. In what may be a surprise to some, she argues that early Christianity recognized the Holy Spirit as a goddess, with an identity connected to and derived from earlier Israelite/Jewish traditions about Asherah and Sophia. She was evidently envisioned as the second member of the Trinity and the divine mother of Jesus. Based on the widespread attestation of this belief, DeConick concludes, “the doctrine of the Mother Spirit as the second person of the Trinity was not heretical to begin with. It only became heretical in the Greek and Latin west in the second century and in the Syriac East 200 years after that” (38). Of particular interest to Latter-day Saints may be the fact that the Mother Spirit was invoked in Aramaic Christianity’s baptism and eucharist rituals. The baptismal waters were seen as a symbolic womb from which converts emerged transfigured and reborn, after which they were given milk to drink.

Probably much less surprising to most Mormons is DeConick’s observation that several stories from the New Testament indicate that Jesus was something of a women’s advocate. His concern for women’s issues, she says, “was not a fringe or marginal aspect of his mission. On the contrary, it was central” (51). Women seem to have ranked among his disciples and he frequently spoke out on domestic and social issues in ways that were favorable to women. For example, in Jesus’s reinterpretation of God’s laws against adultery, he emphasizes that “men had the responsibility to avert their eyes and keep their hands to themselves,” which is remarkable in view of the “general ancient worldview that the locus of lust was the female body, which was the sexual downfall of men” (44).

In her discussion of Christianity’s development in the immediate aftermath of the death of Jesus, DeConick notes that “women were not restricted in the leadership roles they could assume. They were functioning in a range of offices as apostles or missionaries, prophets, church leaders, deacons, and patrons” (73). For at least some women this was because they believed that in the spiritually transformed realm of the church there was “neither male nor female,” but that God’s image encompassed both the male and the female.

Soon, however, the activity, voices, and memories of women and female divinity in the early church were obscured and forgotten and replaced with misogynist narratives and interpretations that saw the female body as naturally deficient and responsible for “the distortion of human sexuality” (149). Paul’s teaching in 1 Corinthians that women were to veil themselves appears to have been intended to counter the practice of women taking on public roles in the Corinthian church and to assert the divinely ordained primacy of the male patriarch in both religious and domestic spheres, which he justified by interpreting Genesis 1:27 through the lens of Genesis chs 2-3. According to DeConick, Paul’s interpretation of Genesis was “radically patriarchal,” since it “[severed] the female from ever becoming God’s image” (73).

This patriarchal interpretive trajectory only seems to have become more entrenched and prevalent over the course of the next century in the Apostolic churches. In conflict with Marcionite teachings, the Pastoral letters “severely censored and subordinated women in the church” (73). Women were forbidden to teach and have authority over men. Their role was confined almost solely to the domestic sphere, where as submissive wives and mothers they would find salvation through childbearing and faithfulness, a view which again is supported through a misogynist reading of the Genesis story.

Eventually the form of Christianity that became normative in the West settled into Roman society and lost touch with its earlier radical social vision and teachings. Female authority was “eroded, limited, and denuded by the male leaders” and “the full weight of sexuality as an evil impulse… laid permanently in their laps” (112).

As disturbing as this description of the gradual marginalization and vilification of the female in early Christianity is, for DeConick, what is most disturbing is that “the misogynist narrative was made sacred or holy, so that it rather than the authentic narrative, became Christianity’s truth” (147). A tradition of “holy misogyny” became the foundation for later Christian views about God (or the Trinity) and the justification for female exclusion from priestly roles.

Upon reading DeConick, the question that naturally comes to my mind is the extent to which Mormonism as a culture has bought into this long-lived tradition of holy misogyny. Are our views about God and priesthood in some sense a perpetuation of religious ideas and norms that earlier had resulted in the devaluation of the female?

More specifically, do we engage in holy misogyny when we value females primarily for their domestic roles? Do we engage in holy misogyny when we encourage passivity and submissiveness among women by keeping them in a subordinate position to male priesthood? Do we engage in holy misogyny by emphasizing female modesty as the key to maintaining traditional social mores? Do we engage in holy misogyny when we fail to do anything to expand upon the distinctive LDS doctrine of Heavenly Mother as a symbol of the divine potential of women? Do we perpetuate holy misogyny when we use biblical scripture, which was developed and canonized at the same time that the tradition of Christian misogyny was taking shape and becoming institutionalized, to justify the exclusion of women from the priesthood and the restriction of public recognition of Heavenly Mother?