Donald Cardinal Wuerl, Archbishop of Washington, D.C., in delivered a report yesterday at the Synod of Bishops in which he named several saints as examples of the “boldness born of confidence in Christ,” a “quiet boldness,” to which the Church’s members are called in the New Evangelization.

First on the list? St. Maximilian Kolbe, the Franciscan Friar canonized by John Paul II as a “martyr of charity,” whose intercession led me into the Catholic Church (as I share in a video here).

St. Maximilian is a particularly apt saint for the New Evangelization because of his heroic witness to truth against what has come to be called, in the words of Pope Benedict XVI, the “dictatorship of relativism.” Here are the words he published that moved the Nazis to send him to the Auschwitz death camp:

No one in the world can change Truth. What we can do and should do is to seek truth and to serve it when we have found it. The real conflict is the inner conflict. Beyond armies of occupation and the hecatombs of extermination camps, there are two irreconcilable enemies in the depth of every soul: good and evil, sin and love. And what use are the victories on the battlefield if we ourselves are defeated in our innermost personal selves?

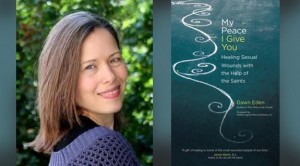

In my book My Peace I Give You: Healing Sexual Wounds with the Help of the Saints, I share how St. Maximilian’s prayers and witness showed me what the Communion of Saints is all about. Recently I wrote some additional thoughts on him at the request of Holy Souls Hermitage blogger Father George David Byers:

One of my favorite stories about St. Maximilian is how, after having volunteered to take the place of a fellow Auschwitz inmate who was condemned to die in a starvation cell, he transformed his environment with his presence. Crammed into a small, dank room with nine other men, deprived of clothes, food, and water, Kolbe convinced his fellow cellmates to join them in prayers, the rosary, and hymns. Nazi guards patrolling the prison, expecting to be confronted with the desperate moans and sobs of dying men, were shocked to find instead that it sounded as though they were in a church.

A surviving witness—an inmate who had been called to act as translator—later reported that the Nazi guards marveled in wonder at Kolbe. Their ideology had taught them to strive to be godless “supermen,” defining themselves by the brute power with which they could subjugate others. In the naked, starving priest, the Nazis were stunned to discover a true man, one who could face death with a smile because he was dying not for hate, but for love.