The Solemnity of SS. Peter and Paul

This past Sunday, we celebrated the martyrdoms of St. Peter and St. Paul. This is kind of unusual: Solemnities are often displaced by Sundays. Advent, Lent, and Eastertide all rely fairly strongly on their week-by-week structure as seasons, so their Sundays take precedence (and most solemnities are either directly tied to Easter, or fall somewhere from December to March); however, Trinitytide has comparatively little structure, so most of its Sundays give way to solemnities.

Jésus-Christ Ressuscité Entouré de Saint Pierre,

Saint Paul, et Deux Anges [Jesus Christ

Resurrected, Accompanied by St. Peter, St. Paul,

and Two Angels], 16th c., by Antonis Mor.1

There’s a tradition that Paul was martyred one year to the day after Peter. This might just be a legend, but I see no particular reason to be skeptical of it, and I incline toward accepting small-t traditions of this sort (at least provisionally, unless I have a particular reason to doubt them).

If you went to a vigil Mass, you’ll have heard John 21:15-19 as the Gospel, while at a Mass on Sunday you’ll have heard Matthew 16:13-19. I’ve translated both of these Gospel texts before, but I’ve done surprisingly little of the Pauline corpus, so I decided to do an epistle this time. I went with the text for the vigil, which comes from Galatians 1. (The epistle for the day proper is from II Timothy 4. If the traditional account of its authorship is correct, II Timothy was probably St. Paul’s very last letter.2) I have, with some reluctance, postponed the prefatory material I was going to incorporate in this post, since it’s not crucial to this specific part of Galatians—so, let’s jump right in.

Galatians 1:11-20, RSV-CE

For I would have you know,a brethren, that the gospel which was preached by me is not man’sb gospel. For I did not receive it from man, nor was I taught it, but it came through a revelation of Jesus Christ. For you have heard of my former life in Judaism, how I persecuted the church of God violently and tried to destroy it; and I advanced in Judaism beyond many of my own age among my people, so extremely zealous was Ic for the traditions of my fathers. But when he who had set me apart before I was born, and had called me through his grace, was pleased to reveal his Son to me, in order that I might preach him among the Gentiles, I did not confer with flesh and blood, nor did I go up to Jerusalem to those who were apostles before me, but I went away into Arabia;d and again I returned to Damascus.

Then after three years I went up to Jerusalem to visit Cephas, and remained with him fifteen days. But I saw none of the other apostlese except James the Lord’s brother. (In what I am writing to you, before God,f I do not lie!)

Galatians 1:11-20, my translation

For I will have you know,a brothers, the good tidings told through me, that this is not from a humanb; for I did not receive this from a human, nor was I taught it, but through a revelation of Jesus the Anointed.

For you have heard of my behavior when in Judaism, that with abundance I chased down the assembly of God and laid her waste; and I cut a path forward in Judaism over many of my peers in my generation, for I was ready to be more exceedingly ferventc over my forefathers’ tradition. Yet, when it pleased him, who set me apart from my mother’s insides and called me according to his grace, to unveil his son before me in order that I might tell the good tidings about him among the nations, I did not consult right away with flesh and blood, nor go up to Jerusalem to those who were emissaries before me, but went out into Arabia,d and later returned again to Damascus.

Thereafter, three years later, I went up to Jerusalem to get acquainted with Kefas, and stayed with him fifteen days; yet I did not see any other of the emissaries,e except Jacob the brother of the Lord. The things I am writing to you, see, before the face of God,f that I am not lying.

Textual Notes

a. would have you know/will have you know | Γνωρίζω [gnōrizō]: I note, with mild amusement, that the RSV instinctively softens things just a tad by changing it to “would have you know.”

A portrait of St. Paul (16th c.) thought to be

by Lucas van Leyden, a painter and

printmaker of the northern Renaissance.

b. is not man’s/is not from a human | οὐκ ἔστιν κατὰ ἄνθρωπον [ouk estin kata anthrōpon]: A translation even more old-fashioned or flat-footed than mine would likely read “is not according to man.” That word κατὰ there appears at the head of all four canonical Gospels—hence their identifications as “according to” so-and-so. The word’s root meaning is something like against, but as in the sentence “she propped her bike against a tree.” It can therefore take either of two extended senses: one of opposition or tension, as when two things push in opposite directions; or one of accord, derivation, or dependence, as when one thing relies on another. (Which sense applies is determined by the case3 of the noun κατὰ governs.)

c. so extremely zealous was I/I was ready to be more exceedingly fervent | περισσοτέρως ζηλωτὴς ὑπάρχων [perissoterōs zēlōtēs hüparchōn]: Once again I find myself disappointed and frustrated by the seeming pointed refusal of New Testament translators to render vivid sentences in vivid language! The RSV rendering of ὑπάρχω [hüparchō] as a mere connective verb is weird; it’s not wrong, but it’s so bland. It can mean “to be,” but in that sense where it’s almost an action instead of a state. The way you might hear a line of dialogue like, “You wanted to be in charge? Well, here’s your chance: be in charge”? That second use of be is the sense ὑπάρχω can carry. Hence my preference for the sense “to be ready”—the point Paul is making is, he was just itching for an opportunity to be an extremist for his idea of the Torah.

d. went away into Arabia/went out into Arabia | ἀπῆλθον εἰς Ἀραβίαν [apēlthon eis Arabian]: The “Arabia” in question here is presumably the Nabatean Kingdom, located in what is now Jordan, the Sinai Peninsula, and the northwestern region of Saudi Arabia. (This would be absorbed into the Roman Empire in 106 as the province of Arabia Petræa, named after its capital at Petra. In Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, the exterior of the Temple of the Sun, where the Grail is concealed, was filmed in Petra—it’s at a site known as Al-Khazneh or “the treasury,” though in fact it is thought to have been a mausoleum;4 it was carved out of the bedrock, close to or perhaps during the time of Christ.)

Al-Khazneh as seen from the mouth of the Siq

[“the Shaft”], the main entrance to Petra.

Photo by Wikimedia contributor Azurfrog,

used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

This seems to be the only allusion to St. Paul’s sojourn in Nabatea in the entirety of the Bible (Luke, if he knew of it, passes quietly over it). What he was doing there is not known. There seem to be two principal theories, which are not mutually exclusive: the first, that he was making his first, novice efforts at evangelizing there; the second, that he was studying the doctrine he had just accepted.

I tend to think it was the second, and probably not the first—at least, not until he had mastered the theology, which would doubtless have been substantially easier for a Pharisee who was already well-versed in the Hebrew Bible. This would make his withdrawal to Arabia a little reminiscent of Jesus’ own period in the wilderness after his baptism (recounted in Matthew 4, Mark 1, and Luke 4).

Given when Paul’s “three years in Arabia” would have been (the late 30s or perhaps earlier), it might not sound like there could be much Christian doctrine to study. However, while it may not have existed in written form yet, the main content of the Synoptics was already being studied. We know this from the description of the primitive life of the Church in Acts 2; “the apostles’ doctrine” would presumably have meant memorizing the collected sermons and sayings of Jesus, this being a partly oral culture.

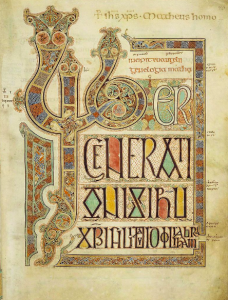

However, at risk of exciting laughter from many New Testament scholars, I’m going to advance a (speculative, tentative) idea that does seem, to me, perfectly possible. I gather that literacy rates among Jews were higher than is typical of agrarian societies, even as far back in their history as the Iron Age.5 If one accepts Matthean priority (a minority position now, but one I find credible and which was the unanimous opinion of the ancients), I see no particular reason why St. Matthew6 couldn’t have written his Gospel shortly after Pentecost, for the express purpose of instructing the infant Church.7 It is topically arranged: five sets of discourses, narratives, and miracles, each set corresponding to one of the five subdivisions of the Pentateuch; these are bookended by the Nativity on one side, and the Passion and Resurrection on the other—which makes for a nice seven-part structure that evokes the days of creation, or (by dividing the Passion and Resurrection) an eight-part structure that matches the Heptateuch and then aligns Jesus resurrected with the Davidic book of Samuel. It’s a catchy structure for catechesis.

If this theory holds water (and I repeat that it is highly speculative!), Paul might have taken a copy of Matthew with him “on retreat” in Nabatea and become familiar with it there. Or, if there’s anything in the Q hypothesis,8 maybe he took a copy of Q with him.

This page from the Lindisfarne Gospels is

actually the first leaf of Matthew—the Latin

begins Liber generationis IHU XR, “The

book of the genealogy of Jesus Christ”.

e. I saw none of the other apostles/I did not see any other of the emissaries | ἕτερον δὲ τῶν ἀποστόλων οὐκ εἶδον [heteron de tōn apostolōn ouk eidon]: It’s interesting that St. Paul wishes to stress this so much, and also interesting that he apparently had so few visitors and acquaintances among the Twelve. The latter may easily be an artifact of his previous role as a persecutor, and it wasn’t only the Twelve; just after our text, Paul goes on to explain that “I was unknown by face unto the churches of Judæa which were in Christ: but they had heard only, that ‘He which persecuted us in times past now preacheth the faith which once he destroyed.'” Forgiveness is not optional for any Christians, but even so, there are individuals for whom and circumstances in which forgiveness is particularly hard to practice, and it may take a long time to achieve it. One can even, perhaps, see a certain divine tact in assigning the role of “apostle to the Gentiles” to a convert whom the Christians of Judea would be, excusably, unenthusiastic about spending time with for quite a while.

The importance of his isolation in this context is, to all appearances, simply to confirm that he did not derive his understanding of the gospel from others (though he did confirm with both St. Peter and St. James, the two most recognized leaders in the Church at the time, that they had the same gospel).

f. before God/before the face of God | ἐνώπιον τοῦ θεοῦ [enōpion tou theou]: Here again we have a less versus a more vivid translation, directly corresponding to the choice between being less or more literal. The word ἐνώπιον is ultimately derived from ὤψ [ōps], meaning “face” or “eye” (from which we get the term optics).

View of Mount Sinai (1572), by El Greco.

However, this wording also has thematic resonance, because of where Paul is going with this letter. In Galatians 3, Paul begins talking about the relation between the promise given by God to Abraham and the revelation which took place at Sinai.9 II Corinthians 3-5 also evokes this, in a similar passage about the Law, and a letter in which Paul is similarly concerned to establish the basis of his authority with his readers; he there takes the veil worn by Moses as a motif. When juxtaposed with his language elsewhere, about abolishing the “wall” or “hedge” that stood between Jews and Gentiles by means of the Cross, we may hear an echo of the Synoptic tradition11 that the Veil of the Temple was torn in two at the moment of Christ’s death; both Galatians and II Corinthians also carry a distinct impression of the episode in Exodus 33 in which God consents to show Moses “the back” of his glory.

Footnotes

1To be honest, I felt like I had to use this painting because it’s such a weird composition. Is something … going on? Why do all the figures have expressions on their faces like they’re confused to be here, and secondarily confused that the others are here? Why is one of the angels trying to crown Christ with flowers—are they supposed to be better than the crowns he has already? Why does that angel sort of have Tilda Swinton face? The more I look at it, the less sense either the whole or the parts make!

2Much of modern New Testament scholarship denies that the Pastorals (I Timothy, II Timothy, and Titus) are really by Paul. I find the cited grounds for doing so—namely, ostensible differences in Pastoral vs. Pauline theology and in the use of certain key terms, like πίστις [pistis], “faith”—supremely unconvincing, for several reasons. Variations in style are natural over a career of twenty-odd years, and the Pauline corpus also features secondary authors and/or amanuenses in half its contents (Romans, I Corinthians, II Corinthians, Philippians, Colossians, I Thessalonians, and II Thessalonians). As for differences in theology, if they’re big enough—like “God hath raised Jesus from the dead” in one letter, versus “No he hathn’t” in another—then sure, those likely tell against authorship by the same man. However, when the inconsistencies scholars claim to discern are between, e.g., Galatians 3:28 and Ephesians 5:24—in other words, when the “difference in theology” depends upon accepting the scholar’s own interpretation of a passage—I grow suspicious. (As if any two randomly selected texts from St. Paul must be addressed to the same aspect of the same topic just because they both include the word “women,” even if the point and context are in both cases completely different!)

3If you’re not familiar with noun case, English does have this, but only in pronouns. For example, he, his, and him are all “the same word” in the sense that they point to the same concept (a third-party male), but the form of the word is different, depending on what the word is doing in the sentence—subjective he for the subject of a clause, possessive his if he’s modifying some other noun, and objective him if he’s the object of a preposition or a verb; subjective, possessive, and objective are the cases of our pronouns. Languages with more inflection than English use a version of the same system for nouns as well, and generally have a larger number of cases. Koiné Greek has five: Its nominative, genitive, and accusative cases are pretty close to the English subjective, possessive, and objective, and it also has a dative case for indirect objects and a vocative case for direct address. Prepositions can go with the genitive, dative, or accusative cases—sometimes with two or even all three, with different meanings depending on the case used.

4It reputedly received the name Al-Khazneh (الخزنة) from local Bedouin in the nineteenth century, based on a belief that treasures were concealed inside.

5This bibliography collates several academic articles on the subject, dating from 1979 to 2007. This postdates the time of Jesus, but the high priest Joshua ben Gamaliel, who reigned in the early 60s (shortly before the First Jewish War), even instituted a type of public school system, to set up schools that would teach basic literacy to children in every town in Judea.

6If the author was St. Matthew, of which we don’t have proof. But again, I see no particular reason to find this tradition incredible, or even unlikely. It is early, widespread, and (to my knowledge) undisputed in the ancient Church; moreover, it’s more than plausible that Matthew, as a former tax collector, would have been literate, and that he would have known Greek. Most significant of all, to my mind, if the Gospel were merely being passed off as an apostolic work, there were more celebrated figures in the ancient Church whose names the forger might have used, and which other forgers did use—Peter, James, also James, John, Andrew, Thomas, Mary Magdalene, and the Mother of God, to name just eight: why pick an Apostle whose principal claim to fame is that he wrote a Gospel—a reputation he presumably didn’t have at the time?

7It might seem strange that he would write a Gospel while the Eleven were all still alive, but with all the international visitors in Jerusalem—the most remote mentioned in Acts 2 came from Rome and Parthia, or in modern terms Turkmenistan—it might have made sense to send them off with a book, at least until one of the Apostles (tradition would suggest Thomas) had had time to prepare for such a far-flung journey. However, I want to stress, this is very much a conjectural explanation for a theory that’s conjectural in the first place!

8If you’re not familiar with the Q hypothesis, it’s the idea that the common material that appears in both Matthew and Luke but not in Mark is based on an earlier, now lost, document, referred to as Q (from the German Quelle “source”). This is generally esteemed to have been a “sayings” Gospel with little or no narrative, something along the lines of the Gospel of Thomas.

9Note verse 19, which states, interestingly, that the Law “was ordained by angels in the hand of a mediator” (emphasis mine), “a mediator” presumably being Moses. The idea that Moses received the Law through angels is not stated directly in the Torah; it may have formed part of the Oral Torah of the Pharisees, or been an element of Essene belief, or quite possibly both. The Sadducees did not accept even the existence of angels, and as far as I can tell they played little part in Samaritanism.10 Paul’s allusion in 4:9 to “elements”—other translations have “forces,” “elementary principles,” “elemental powers,” etc.—may be referencing the same thing: a class of angelic beings, referred to by Catholics under the name Virtūtēs (traditionally “Virtues” in English, though “Forces” or “Efficacies” would be better nowadays), which govern the natural realm. If this identification is correct, then probably St. Paul is either saying that the Virtūtēs were the intermediaries who delivered the Torah to Moses, or using an allusion to them as a synecdoche for angels in general—just as we do ourselves when we refer to all nine orders as “angels,” a term which technically only denotes the ninth order (our guardian angels).

10The best sources I was able to find on Samaritan theology were, unfortunately, modern documents—one an entry from the Jewish Encyclopedia of 1906, the other a summary and review for a University of Chicago journal of a book on Samaritanism (curiously, also from 1906)—which must be taken with that reservation. These sources indicate that Samaritans believe in angels, but do not assign them any great theological import.

11See Matthew 27:51 and Mark 15:38. The material shared specifically between Matthew and Mark, but not Luke, is sometimes called the “double tradition.”

NOTE: This post was edited the day after publication, mostly to correct some typos and ambiguous phrasing.