THE MAKERS of Priest claim that their film is meant to be a catalyst for change within the Catholic church, but their confrontational approach does more harm than good to their cause.

THE MAKERS of Priest claim that their film is meant to be a catalyst for change within the Catholic church, but their confrontational approach does more harm than good to their cause.

Worse, they have mounted the assault on too many fronts at once. In the space of 100 minutes, Priest tries to address issues as diverse as homosexuality, celibacy, the secrecy of the confessional, child abuse, liberation theology, the problem of evil … even a pinch of animal rights. It’s a wonder the ordination of women never comes up.

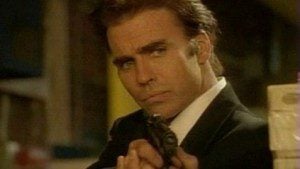

Father Greg Pilkington (Linus Roache) is, at first glance, a somewhat naive and rigidly moralistic priest who berates his roommate, Father Matthew Thomas (Tom Wilkinson), for enjoying a longstanding affair with their housekeeper (Mona Lisa’s Cathy Tyson). Greg preaches individual responsibility for sin; Matthew preaches on the evils of the social elite; they find each other’s sermons “offensive.”

Just when you think Priest is shaping up to be a theological Spy vs. Spy, Jimmy McGovern’s script tosses in the monkey wrench. To escape his troubles, Greg visits a gay bar and picks up a partner, Graham (Robert Carlyle) for some intense but casual sex. As often happens in film, the one-night stand soon becomes a case of true “love.” Before you can say “overnight scandal,” the two are caught by a police officer, and the parish is up in arms. At which point a polarized slugfest ensues — not between Matthew and Greg, but between the priests and their congregation.

Instead of a dialogue between these two camps, both sides lob Bible verses at each other as if they were grenades. “It’s an abomination!” barks one layman; “Judge not lest ye be judged!” barks the priest. “God destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah!” barks the layman. “You are without sin, cast the first stone!” barks the priest. And so on. Advocates on both sides of the homosexuality debate have detailed responses to the other side’s favorite verses, but none surface in this film.

The film stumbles deeper into its theological quagmire as it tackles the issue of pedophilia. An abusive father (Robert Pugh) justifies his actions on the grounds that, in his view, all fathers secretly want to molest their children.

This is a truly horrid concept, but how is his logic any different from Father Matthew’s addle-brained appeals to “common humanity”? Both men justify their desires with self-serving beliefs about human nature and both men — even Father Matthew — leave God out of the equation altogether. Are we to side with Father Matthew because he likes Chilean music and knows how to take a joke, while the abusive father does little more than spook Father Greg with his smug glares? Beyond these stock clichés, Priest offers no grounds for discernment.

One wonders what seminary produced such priests. Father Matthew can certainly make use of Christ’s teachings when they suit his purpose, but at times his quips betray a woeful ignorance of the Gospels. “To call another human being Satan — what sort of religion is that?” A good question, but why does Jesus call St. Peter “Satan” in Mark 8:33? Similarly, while pooh-poohing the furore around homosexuality, he asks his congregation if God really “gives a damn” how men use their genitals, but if God’s got time for the sparrows (Matthew 10:29-31), it stands to reason he does care about things that people treat as unimportant.

Father Greg betrays a similarly docetic ignorance of Jesus’ humanity; to him, and to the film at large, Jesus remains solely “divine” — which, to the filmmakers, means that he is aloof, vague, and ultimately irrelevant. It is one of Priest’s central ironies that Father Greg is staring at a crucifix when he complains that Jesus, never having any doubts or problems of his own, cannot relate to human trials.

To its credit, Priest tries to wrestle honestly with questions of temptation and faith. Father Greg confesses to another priest that prayer does not help him in his struggle to remain celibate because the crucifix and its “utterly desirable naked man” distract him: “I turn to him for help, and it gets worse.” As hot under the collar, as some Christians may get at such dialogue, this is a very real dilemma for those who wrestle with the issue of homosexuality. Covering our ears won’t do.

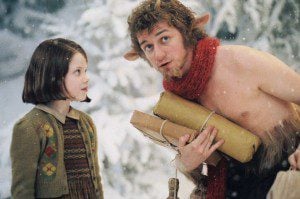

Director Antonia Bird’s welcome sense of humour manages to relieve some of the film’s heavy-handedness, and Priest concludes with the most powerful portrayal of forgiveness since the native South Americans sank Robert De Niro’s armour in The Mission.

But taken as a whole, Priest is ultimately unsatisfying. If it is meant as a sermon, it offers too many red herrings; no cogent argument prevails. If it is meant to be a dialogue, it is hopelessly inarticulate and one-sided. The issues raised in this film need to be discussed over a table, one at a time, not slapped on the walls of a public bathroom.

— A version of this review was first published in BC Christian News.