IN ADDITION to the social and political havoc it caused, the First World War precipitated a sort of spiritual crisis. In a world rapidly giving in to industrialism and modernization, the war proved that science, far from saving the world, was just as likely to speed it along to its destruction. And with so many people killed or missing in the conflict, survivors were left to wonder if they would ever see their loved ones again, in this life or the next.

IN ADDITION to the social and political havoc it caused, the First World War precipitated a sort of spiritual crisis. In a world rapidly giving in to industrialism and modernization, the war proved that science, far from saving the world, was just as likely to speed it along to its destruction. And with so many people killed or missing in the conflict, survivors were left to wonder if they would ever see their loved ones again, in this life or the next.

Two recent movies made for children, based on true stories set in this period, answer that question strongly in the affirmative. But in doing so, they play fast and loose with the known historical facts.

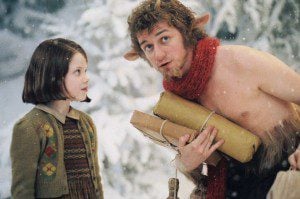

FairyTale: A True Story tells the tale of two girls, Elsie Wright (Florence Hoath) and Frances Griffiths (Elizabeth Earl), who caused a sensation in 1920 when they took several photographs of themselves playing with fairies in the fields behind their house in Cottingley, a small Yorkshire town.

Apart from a few skeptics — chief among them Harry Houdini (Harvey Keitel) — everyone who sees these pictures assumes they offer proof of the spirit world and a chance to communicate with dead relatives, though it’s not at all obvious why they should. If it were ever proved that little people with wings really do hide in the north of England, I can’t imagine it would do more than complicate most theories of evolution.

But the photographs are given a spiritual significance once they catch the attention of Edward Gardner (Bill Nighy), a connoisseur of the occult from the Theosophical Society, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Peter O’Toole), the creator of Sherlock Holmes and an avowed spiritualist who, swayed by the belief that neither cameras nor children could ever lie, publicizes the girls’ photos in Strand magazine.

The film, directed by Charles Sturridge (TV’s Gulliver’s Travels), swallows the girls’ story whole and brings the fairies vividly to life, casually ignoring the fact that, in the early 1980s, both Elsie and Frances admitted that most, if not all, of the photos had been faked. (Frances did insist that one of them was genuine.)

Moreover, it invents a subplot in which a cynical, buffoonish reporter (Tim McInnerny) encounters the ghost of Elsie’s dead brother (James Danaher), despite the fact that, historically, Elsie was an only child.

Such dramatic liberties seem trivial next to Anastasia, which re-writes the events surrounding the Russian Revolution so thoroughly it becomes a sort of screwball action movie cum Broadway musical inspired by the Brothers Grimm.

Such dramatic liberties seem trivial next to Anastasia, which re-writes the events surrounding the Russian Revolution so thoroughly it becomes a sort of screwball action movie cum Broadway musical inspired by the Brothers Grimm.

In this telling, the monk Rasputin (voiced by Christopher Lloyd) is a wicked magician who, banished from the Tsar’s imperial court, places a curse on the Tsar’s family. When his little green demons stir the people of Russia to revolt, the royal family is presumably captured and killed offscreen, except for the Dowager Empress (Angela Lansbury), who flees to Paris, and eight-year-old Anastasia (Meg Ryan), who spends the next 10 years in an orphanage in a state of amnesia.

When Anastasia emerges, a teenager dressed in rags, she meets Dimitri (John Cusack), a con man who hires her to impersonate herself so he can take her to Paris and collect the reward money offered by the exiled Empress, who yearns to see if any of her family survived. Of course, there are complications: the latent princess and the scruffy con man begin to fall in love, and the ghost of Rasputin is still out there, lurking in the underworld and waiting for a chance to kill the last of the Romanovs.

Obviously, director Don Bluth (who last visited Russia in An American Tail) is not offering a sober reconstruction of history here. It is true that several women claimed to be Anastasia, but none were ever accepted by the Tsar’s surviving relatives. Indeed, the remains of the Tsar and his family, including Anastasia, were ultimately discovered just a few years ago; the Russian government and the Orthodox church are currently wrangling over where the bodies ought to be buried.

Bluth never lets such details get in the way of his modern fairy tale. Anastasia lives and gets to have it all: she is not only restored to an insulated world of “glittering jewels and fine titles” far removed from the smokestacks that made her homeland so “bleak” and “grey,” she even gets to elope with a commoner and, in a gesture so empty she ought to be insulted, she is proclaimed “heir to the throne” (what throne?).

Tinkering with history is nothing new to the cinema — indeed, it’s sometimes necessary for dramatic purposes — but there is something rather disquieting about the way in which these two films go about it.

Both films are set in a period when a wary, modernist public demanded proof of fanciful claims. Each film is based on a mystery that had its origin in that period, a mystery that staked its reputation on the notion that it could somehow meet such demands for proof. And both films happily ignore the fact that, in the end, the claims were proven false.

There is, it seems to me, something inherently dangerous in this, especially when your target audience is a young and impressionable one that still relies on grown-ups to sift fact from fiction. When people demand a reason to believe, it’s better to give them no reason at all than to lie through your teeth.

— A version of this review was first published in BC Christian News.