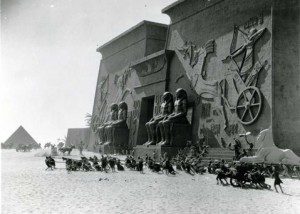

Movie sets often feature archaeological remains, but how often do they become archaeological sites in their own right? Parts of Cecil B. DeMille’s first version of The Ten Commandments were filmed on a massive set built in the sand dunes near Guadalupe, California. To prevent competitors from shooting their own films on the site and beating him to the box office, DeMille buried the set under the sand once he was done, and there it lay undisturbed for 60 years.

Movie sets often feature archaeological remains, but how often do they become archaeological sites in their own right? Parts of Cecil B. DeMille’s first version of The Ten Commandments were filmed on a massive set built in the sand dunes near Guadalupe, California. To prevent competitors from shooting their own films on the site and beating him to the box office, DeMille buried the set under the sand once he was done, and there it lay undisturbed for 60 years.

In 1983 New York University film-school grad Peter Brosnan came across a cryptic passage in DeMille’s autobiography, in which the director mused: “If, a thousand years from now, archaeologists happen to dig beneath the sands of Guadalupe, I hope they will not rush into print with the amazing news that Egyptian civilization, far from being confined to the banks of the Nile, extended all the way to the Pacific coast of North America.”

Rather than wait a thousand years, Brosnan and some fellow film buffs went to California in search of the buried ruins. “This was right after the first El Nino winter, one storm after another all winter,” recalls Brosnan, now 46. “Those storms had wiped about two or three feet of sand off the dunes, so when we went out there, there were just acres of statuary staring up at us out of the sand.”

California has since deemed the former movie set an official archaeological site. In 1990 the Bank of America sponsored a survey using ground-penetrating radar, which appears to have found DeMille’s sphinxes. However, the sphinxes remain buried for now; funding for the prospective dig has been hard to come by, even in memorabilia-conscious Hollywood.

Brosnan says the project’s real value lies in what it can tell us about everyday life among the 2,500 people who spent a month living on the set. For example, his team has found many bottles of cough medicine, a common substitute for liquor during Prohibition because it contained “a big wallop of alcohol.” (Some charioteers — actually soldiers from Monterey — preferred the speakeasies in Guadalupe, where they occasionally held chariot races in the street.)

Brosnan has compiled more than 40 hours of interviews with people who worked on the film, many of whom are no longer alive. He wants to produce a documentary on this bit of Hollywood history, but he’s still waiting for the perfect money shot, as they say in the business. “We need to see a sphinx coming out of the sand for pure dramatic effect,” he says, tongue partly in cheek.

The project’s Web site can be found at www.lostcitydemille.com.

— A version of this article was first published in Bible Review.