By now, it’s become standard practice for filmmakers tackling the gospels to say that they will show Jesus in a more ‘human’ light. What this usually means is that the Jesus in their films will smile more often than the Jesuses in other films. He will laugh, he will cry, he will help the fishermen with their nets, he may even get up and dance at parties.

By now, it’s become standard practice for filmmakers tackling the gospels to say that they will show Jesus in a more ‘human’ light. What this usually means is that the Jesus in their films will smile more often than the Jesuses in other films. He will laugh, he will cry, he will help the fishermen with their nets, he may even get up and dance at parties.

But this definition of humanity, with its implicit assumption that God, in his divinity, is somehow above all that stuff, does a disservice to both sides of the equation. The God of the Old Testament definitely has feelings, so emotion itself is no big sign of humanity. If Jesus is fully human, as the creeds insist, then there has to be more to it than that.

To be human is to be like the actor in a play, finding our role and performing it to the best of our ability, while trusting in a director who knows how our actions fit into the bigger story, even if we do not.

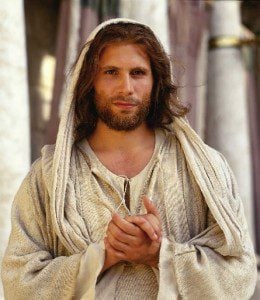

And the CBS mini-series Jesus, broadcast across North America last month and soon to be released on video, may be the first film I have seen which takes this understanding of humanity seriously, without negating the divinity of Jesus the way some of the more notorious films seem to do.

Jesus is the latest installment in ‘The Bible Collection,’ a series of TV-movies which have generally treated their protagonists as full-bodied characters teeming with conflicted passions. Ben Kingsley’s down-to-earth interpretation of Moses, for example, had very little in common with Charlton Heston’s statuesque posturing in The Ten Commandments.

The best films in the series so far, Moses and Joseph, were directed by Roger Young, who also oversees Jesus. Working from a script by Canadian screenwriter Suzette Couture, Young takes Jesus (Jeremy Sisto) through many of the same plot beats that previous episodes took their biblical heroes, including moments of doubt and possible romantic attraction (in this case between Jesus and Mary, the sister of Lazarus).

The film also shows Jesus living his teachings, instead of merely saying them. He turns the other cheek when Barabbas (Claudio Amendola) strikes him on the face, and it’s clear it takes some effort for even Jesus to resist striking back. He also prays. Most films show Jesus praying during the anguish of Gethsemane and before he performs really big miracles — all moments of high drama. But it is rarely shown as part of his ongoing personal relationship with God. Not so here. When Joseph dies, a grieving Jesus asks God to bring him back. But he concludes, “Your will be done.”

If Jesus films are often quite dull, it’s usually because they don’t allow him to become a character in his own right. He has no arc; there is no room for him to develop. We cannot identify with him, as we do with most protagonists; we are meant to simply look at him in awe. That certainly isn’t the case here. When Jesus relents and heals the Syro-Phoenician woman’s daughter, after initially refusing to do so because she is a foreigner, he tells his disciples, “If I can learn, so can you.”

The point of that story, in the gospels, was to show that Christ’s message is not only for Israel, but for the world, too. However, ironically, the film does not convey the specifically Israelite character of Jesus’ mission in the first place all that well. When the historical Jesus chose 12 apostles, rode a colt into Jerusalem, and overturned the money tables, he consciously tapped into, and subverted, the messianic expectations of his fellow Jews. But the Jesus of this film does these things for no obvious reason, and is surprised when the Jews misinterpret his actions.

The film also jumbles its chronology. Most historians agree that the money-table incident took place at the end of Jesus’ career and was the event which directly provoked the authorities to arrest him. But the film puts this incident in the middle of Jesus’ career, at the climax of part one. In part two, things go on as they were before.

Shuffled around like this, the events in Jesus’ life don’t follow much of a pattern or add up to much of a point. Every now and then, as they walk from town to town, Jesus plays tag with his disciples or splashes them with water, but what sort of mission are they on, exactly? What sort of objective are they trying to meet as they roam about the countryside?

At times, the film handles its material too casually. Mary Magdalene (Debra Messing) dresses like a prostitute even when she hangs out with the disciples. Police Academy’s G.W. Bailey plays a Roman official who entertains Pontius Pilate (Gary Oldman) with coarse plays mocking the Jews. And Salome’s (Gabriella Pession) dance for Herod Antipas (Luca Barbareschi) is awfully blasé; it definitely wouldn’t make a man want to give her half a kingdom as a reward.

Unlike earlier ‘Bible Collection’ films, Jesus steps outside of its ancient context. Jesus is haunted by visions of the future, in which nations and churches commit atrocities in his name. Satan (Jeroen Krabbé) visits him in Gethsemane and uses these visions to try to convince him that his death on the cross will be in vain. This is a far more sobering ‘last temptation’ than anything imagined by Martin Scorsese.

Jesus is a far from perfect film, but its imperfections are one of its most endearing and challenging qualities. The last major mini-series about Christ was Franco Zeffirelli’s Jesus of Nazareth (1977), a film some critics found too ‘tasteful’; Lloyd Baugh, author of Imaging the Divine, complained that it predigested the gospel and left no room for discussion.

Jesus, on the other hand, is almost guaranteed to get people pondering anew what it meant for the immortal God to become mortal flesh.

— A version of this review first appeared in BC Christian News.