THERE are two ways to handle a highly controversial issue, especially when you are looking at the form that that issue took several decades ago, before our culture had settled into its current attitudes and assumptions. Two recent films, both of which take place in the post-war era, offer a stark study in contrasts between these two approaches.

THERE are two ways to handle a highly controversial issue, especially when you are looking at the form that that issue took several decades ago, before our culture had settled into its current attitudes and assumptions. Two recent films, both of which take place in the post-war era, offer a stark study in contrasts between these two approaches.

First, there is Kinsey, Bill Condon’s essentially heroic depiction of the zoologist whose studies of human sexuality, published in 1948 and 1953, shocked and outraged North American society. Rather than cause any similar disturbance to present-day audiences, the film mocks the sexual attitudes of the past (some of which do, admittedly, deserve to be mocked) from a safe distance, while flattering us for our supposed enlightenment.

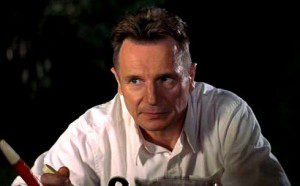

In the film, Alfred Kinsey (Liam Neeson) is a somewhat nerdish expert on gall wasps who becomes convinced that his university students are, at best, not getting adequate information on sexuality, and, at worst, being given lots of misinformation. So he institutes a “marriage” course that gives his students the facts of life, complete with graphic photos.

Emboldened by his success, Kinsey secures funding from the Rockefeller Foundation and begins a nationwide survey on sexual behavior. The non-judgmental attitude he brings to his interviews eventually spills over into his life, as both Kinsey and his wife, Clara (Laura Linney), embark on affairs with research assistant Clyde Martin (Peter Sarsgaard).

Kinsey attracted no small amount of condemnation from critics who accuse his studies of being little more than propaganda for sexual immorality, whether it be promiscuity, bestiality, even pedophilia; Kinsey’s studies are also the source for that popular but long since discredited statistic that 10 percent of the population is homosexual.

But the problem with Kinsey’s studies runs much deeper than mere morality; one thing that is completely missing from Kinsey’s life and work, or at least from this film’s depiction of them, is any sense of the fact that human sexuality has a fundamentally sacred or spiritual component and cannot be reduced to the breeding instincts of wasps and rodents.

Ironically, in its efforts to depict Kinsey as a crusader who affirmed the human dignity of those who engage in taboo practices, the film must accept the dehumanizing premise that people are just another kind of animal. Condon may think Kinsey lifted certain people up, but in making this point, he brings humanity as a whole down a notch or two.

Then there is Vera Drake, Mike Leigh’s exquisitely detailed and complex study of abortions both legal and illegal in 1950s England. Leigh himself has said that he is pro-choice, but his film does not adopt any particular stance on the issue, and indeed, he even gives us room to wonder just how naive the title character is and how much harm she may be causing.

Then there is Vera Drake, Mike Leigh’s exquisitely detailed and complex study of abortions both legal and illegal in 1950s England. Leigh himself has said that he is pro-choice, but his film does not adopt any particular stance on the issue, and indeed, he even gives us room to wonder just how naive the title character is and how much harm she may be causing.

Rather than make a piece of propaganda, Leigh brings to Vera Drake the same painstaking, and essentially compassionate, discipline he brought to earlier films like Secrets and Lies. With all of his films, Leigh spends months developing characters with his actors, and improvising the story in a way that is true to those characters. Once they have finished working on the narrative, Leigh turns it into a script, and then into a film.

The result is a movie that pays close, careful attention to the way people behave, and thus encourages us to pay close attention, too. While Vera Drake certainly reflects Leigh’s perspective, it does not prejudice our feelings. Instead, it encourages us to understand the characters and where they are coming from, just as they try to understand each other.

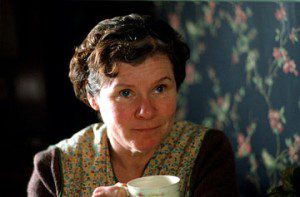

Much of the early part of the film is spent on Vera (Imelda Staunton) and her family life. She invites a new neighbour over for dinner, and he bonds with Vera’s husband over stories of their experiences in the war. This new neighbour also embarks on a touching courtship with Vera’s very shy daughter. But their lives are disrupted one fateful day, when the police come over and arrest Vera for performing illegal abortions.

It turns out one of Vera’s “patients” nearly died of complications from the procedure, and was taken to the hospital, where the doctors quickly figured out what must have happened. And the reason Vera was found so quickly is because the mother of the pregnant woman in question happened to know Vera from many years before. Who knows how many other “patients” might have become ill, too, without Vera knowing about it?

Leigh is fascinated by the way humanity expresses itself around people’s jobs — both by the wide range of clients people encounter, and by how they try to retain a human touch as they go through the motions of helping others. Among other things, he draws an interesting contrast between the patriarchal doctors who offer to secure a legal abortion for an upper-class girl who was date-raped, and Vera’s very matronly way of providing illegal abortions to her “patients” at their homes — and then he shows how the police, of all people, manage to combine both masculinity and femininity, both authority and sensitivity, in their line of work.

Catholic critic Peter Malone has said that watching Vera Drake can be an exercise in hating the sin but not the sinner, and he is absolutely right. Kinsey wants us to cheer a hero of the so-called sexual liberation. But Vera Drake gives us real people and real issues and asks us to engage them in an intelligent, compassionate way. Propaganda, it ain’t.

Kinsey

Internet Movie Database | Movie Review Query Engine

USA: R | BC: 18A | ON: 14A

Vera Drake

Internet Movie Database | Movie Review Query Engine

USA: R | BC: 14A | ON: 14A

— A version of this review was first published in BC Christian News.