LOS ANGELES, CA — There have been surprisingly few films about the Crusades, and most have been ambivalent at best about the legacy of those wars.

LOS ANGELES, CA — There have been surprisingly few films about the Crusades, and most have been ambivalent at best about the legacy of those wars.

Perhaps the biggest Hollywood production until now was Cecil B. DeMille’s The Crusades (1935), a pious romance that impressed future Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser so much that he allowed DeMille to use the Egyptian army as extras in his remake of The Ten Commandments.

Beyond that, there have been one or two other films, including a B-movie starring George Sanders as King Richard and Rex Harrison as Saladin in 1954; and there have been scattered references to the Crusades in films about Robin Hood and Ivanhoe, though the wars themselves are almost always kept well off-screen.

One notable exception to the latter rule was Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991), the very politically correct Kevin Costner film that begins in a prison in Jerusalem mainly so its title character can add a Muslim sidekick to his Merry Men, preaching the virtues of religious diversity.

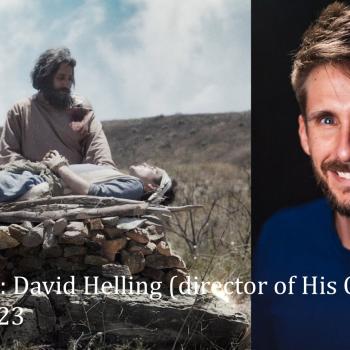

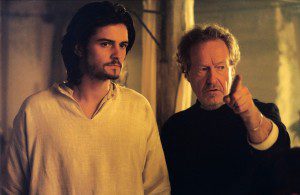

Director Ridley Scott was, therefore, sailing into largely uncharted cinematic waters when he forged ahead with Kingdom of Heaven, his brand new epic about a conflict between Christian and Muslim armies over the Holy Land. And he was very conscious of the fact that his film was coming out at a time when religious conflicts are on the rise around the world.

Speaking to a roomful of mostly Christian reporters, Scott — whose films include Gladiator, Alien and Blade Runner — recalls tackling similar themes in Black Hawk Down, his film about a disastrous American military operation in Somalia. The film was originally scheduled for release in early 2002, but then the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington DC happened in September 2001, and the film’s release date was moved up.

“Whilst that was happening, I had already talked to [Kingdom of Heaven screenwriter] Bill Monahan, whose pet subject is just this period,” Scott says. “I think we would have made this film with or without the Gulf War and with or without 9/11, basically.”

The new film does not actually take place during one of the Crusades, but in the years between them, just prior to the Third Crusade. Scott says the film was deliberately set during this period so that it would end on a “here we go again” note, with King Richard the Lionheart setting out on his own military mission after the film’s battles come to an end.

“Unfortunately we don’t seem to learn from history, do we?” asks Scott. “And you’d think we would. The very last line [in the film] says it’s still going on in the Holy Land, we’re still seaching for settlement. It’s a recycling process that has gone on for 1,000 years.”

Scott says he was drawn to Monahan’s “passion” for the Crusades and the issues raised by them; and he was particularly drawn to the fact that the film’s protagonist, Balian of Ibelin (Orlando Bloom), is a doubter on a spiritual journey, who goes on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem to atone for his sins and finds himself swept up in the politics of the Holy City.

“This character is on a spiritual journey, to reinforce or not his doubts about the existence of God,” says Scott, adding that he identifies with Balian’s skepticism. “I’m agnostic, which means ‘not sure,’ right? So I’m not sure. How many people at this table are agnostic? Put your hands up!”

Scott grins as one reporter tells him he’s in the wrong room. “I’m agnostic because I went through the usual process of parents insisting you go to church and yet they didn’t,” says Scott. “So there’s me, sitting in the chairs, thinking, ‘Jeez, why am I here? I’d rather be playing tennis, seriously.’ And then I was an altar boy, and then it was a year before my parents realized that I actually hadn’t turned up to become an altar boy, and in fact, I was indeed playing tennis for a year on Sunday evenings. So that’s when they said, ‘I guess that’s not for you,’ and I said, ‘Not really.'”

Scott is quick to emphasize that, while he may have his doubts about religious systems and institutions, he doesn’t have a problem with faith, per se — and he notes that Jesus himself, according to at least some interpretations of Luke 17:21, says the kingdom of heaven is within people themselves.

“The word ‘religion’ is only a label,” says Scott. “What lies behind that, the most important thing of all, is the word ‘faith’. You either have faith, or you don’t have faith, or you have degrees of faith — and if you have degrees of faith, then you become agnostic. You’re kind of in-between or you’re on the fence.”

In fact, Scott notes that the most virtuous character in the entire film is a knight known only as the Hospitaller (David Thewlis). “Here’s another big signal in the whole thing. Balian says, ‘I have lost my religion,’ and the Hospitaller says, ‘I haven’t heard that,’ as if he has a direct line to God. He’s the symbol of the one really good man through the film — good man, underlined.

“He doesn’t even get angry when Balian says, ‘I’m not in denial of God, I’m in huge question of the possibility that there may not be this voice that is God.’ And he’s saying, ‘Well, that’s okay.’ He’s trying to ease him in the right direction. And he’s saying, really, if you just start with being a good man every day or not, that’s a pretty good start.”

Leading man Bloom echoes these sentiments when it is his turn to meet the press. He says two of the key themes of the film are the need to accept personal responsibility for one’s own soul, and the virtue of doing what is right, no matter what the cost; at one point, his character refuses to be complicit in the murder of a fanatical knight even though he knows it might buy peace for a time.

“It is about what you do each day for your fellow man,” says Bloom. “That is as close to godliness, being thoughtful to your fellow man.

“The way I see it, we are living on this world which we share, and there has always been jostling for power, and war — whether it’s over money, power, land, religion, oil, water — and we should be able to live in harmony. Surely that’s what any God, whoever your God may be, would tell you. If it isn’t about humanity, then I’m not sure what it’s about.”

Bloom, who played the elf Legolas in The Lord of the Rings and had a small role in Black Hawk Down, says he leapt at the chance to play Balian because he liked the idea of playing a “reluctant hero.” The part also allowed him to take centre stage and “become a man,” after playing second banana to the Pirates of the Caribbean and the Greek heroes of Troy.

“I actually read this script when I was on the plane coming back from shooting Troy, and I had no intention of doing another, like, sword-epic style movie,” he says. “But I read this script and I thought, ‘Wow, this is a great opportunity for me to do something the polar opposite to the cowardly younger brother that Paris was.'”

He also says that, as one who finished drama school just a few years ago and has been blessed with plum roles ever since, he agrees wholeheartedly with the film’s message that making someone a knight can, in and of itself, make someone a better fighter.

“If somebody had said to me that I’d be working with Ridley Scott when I was 27, and that I’d have been the lead in his sword-epic movie that he’d been wanting to make for ages, I’d be like, ‘You’re kidding, aren’t you? That’s not me, really?'” says Bloom. “But I think people can do remarkable things when responsibility is placed on them, and when they have faith and belief that they can do it, and somebody else has faith or belief in them, you know what I mean? And I think that is how you see Balian defending so courageously the walls of Jerusalem at that point.”

As for the film’s reception in other parts of the world — particularly in Muslim countries — Bloom says he went into the project confident that Scott would bring “sensitivity” and “balance” to the story.

And while there are troublemakers here and there in the story, especially among the Knights Templar, Balian has no particular arch-enemy, the way the protagonist in, say, Gladiator did. “So it’s not a conventional movie in that sense,” says Bloom. “But that’s why I think it’s a courageous movie and that’s why I think it’s an important movie.”

— Versions of this article first appeared in BC Christian News and at Christianity Today Movies.